BRUCE SMITH,

Liberty and Liberalism (1887)

|

|

This is an e-Book from The Digital Library of Liberty & Power <davidmhart.com/liberty/Books> |

Source

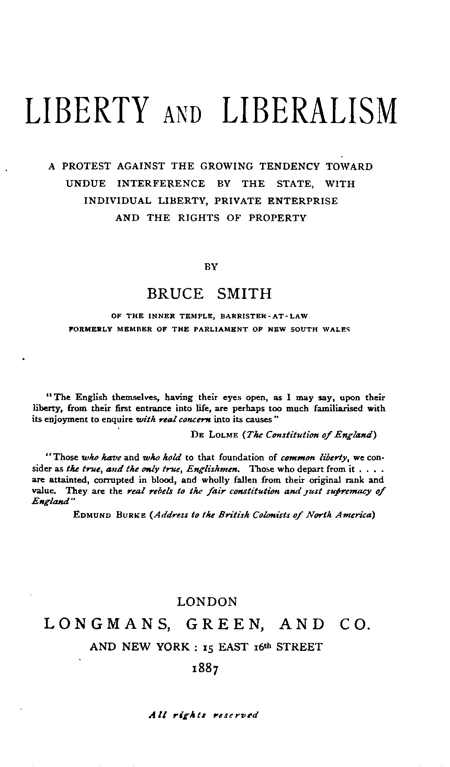

Bruce Smith, Liberty and Liberalism: A Protest against the growing Tendency toward undue Interference by the State, with Individual Liberty, Private Enterprise and the Rights of Property (London: Longmans, Green, and Co.,1887).

Editor's Note

To make this edition useful to scholars and to make it more readable, I have done the following:

- I have inserted the page numbers of the original edition

- I have not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new page (this will assist in making word searches)

- I have added unique paragraph IDs (which are hideen at the moment)

- I have retained the spaces which separate sections of the text

- I have created a "blocktext" for large quotations

- I have moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text

- I have placed the footnotes at the end of the book

"The English themselves, having their eyes open, as I may say, upon their liberty, from their first entrance into life, are perhaps too much familiarised with its enjoyment to enquire with real concern into its causes"

DE LOLME (The Constitution of England)

"Those who have and who hold to that foundation of common liberty, we consider as the true, and the only true, Englishmen. Those who depart from it…are attainted, corrupted in blood, and wholly fallen from their original rank and value. They are the real rebels to the fair constitution and just supremacy of England"

EDMUND BURKE (Address to the British Colonists of North America)

CONTENTS. [short version]

- PREFACE.

- LIST OF AUTHORS QUOTED OR CONSULTED.

- CHAPTER I. "LIBERALISM" AND OTHER CURRENT POLITICAL PARTY-TITLES—THEIR UNCERTAIN SIGNIFICATION. pp. 1-27.

- CHAPTER II. POLITICAL PARTY-TITLES—A SHORT ACCOUNT OF THEIR ORIGIN AND MEANING. pp. 29-65.

- CHAPTER III. HISTORIC LIBERALISM. pp. 66-138.

- CHAPTER IV. MODERN LIBERALISM. pp. 139-199.

- CHAPTER V. THE PRINCIPLES OF TRUE LIBERALISM. pp. 200-254.

- CHAPTER VI. SPURIOUS LIBERALISM—HISTORIC INSTANCES. pp. 255-279

- CHAPTER VII. SOME INFIRMITIES OF DEMOCRATIC GOVERNMENT. pp. 280-327.

- CHAPTER VIII. SPURIOUS LIBERALISM—MODERN INSTANCES. pp. 328-421.

- CHAPTER IX. PRACTICAL APPLICATION OF THE PRINCIPLES OF TRUE LIBERALISM. pp. 422-548.

- CHAPTER X. SOCIALISM AND COMMUNISM. pp. 549-683.

- Endnotes

[ix]

CONTENTS. [long version]

- CHAPTER I. "LIBERALISM" AND OTHER CURRENT POLITICAL PARTY-TITLES—THEIR UNCERTAIN SIGNIFICATION.

Impossibility of obtaining universally accepted definitions of party-terms—British party-titles not applicable in younger communities—Differences between such communities—Attitude of certain section of Colonial "Liberal" Press—Effect of perversion of party-title meanings—"Liberalism" and "Protection" paradoxical terms—Position of Liberals during period of Corn Laws Repeal in Great Britain—"Liberalism" and "Protection" anomalous, apart from history—Influence of Victorian "Liberal" Press—Newspapers a commercial enterprise—Deductions from the fact—Instances of misinterpretation of the term "Liberalism"—Causes of such misconception by the masses—Tendency to look for positive benefits from "Liberal" legislation—Illustrations of "Liberal" and "Conservative" principles as popularly understood—Terms "Liberal" and "Conservative"—Unusual attention drawn to same during last two English elections—Mr. Chamberlain's proposals claimed to be "Liberal" measures—Modern "Radicalism" admitted to be synonymous with "Socialism"—Changes of party-titles in consequence—Alleged changes in principles of certain eminent statesmen—Mr. Bright—Mr. Goschen—Lord Hartington—The Times on the changes in party-titles—Home Rule and consequent party-discussions—Illustrations of change of meaning in terms—Effect of such changes generally—Answers to "Why am I a Liberal?"—The Radical programme—Modern tendency in legislation—Consequent perversion of meanings… - CHAPTER II. POLITICAL PARTY-TITLES—A SHORT ACCOUNT OF THEIR ORIGIN AND MEANING.

History of England the history of its political parties—Use of English party-titles in colonies should give their history an interest for all English-speaking peoples—The year 1641 marks the first use of any party-titles of consequence—Class-divisions previous to that year—In 1641 originated the two great parties which, under different names, have ever since existed—Origin of terms "Cavalier" and "Roundhead"—Principle underlying that party division—Persistency of Charles I. regarding the preservation of his prerogatives—Macaulay's definition of the respective principles of those parties—Terms "Cavalier" and "Roundhead" succeeded by term "Tory" and "Whig"—Origin of term "Whig"—Origin of term "Tory"—Date of their first use—Principles underlying those terms—Socia classes represented by each—Hume, Macaulay, and Hallam on their respective principles—Apparent exceptions in their continuous representation of the same principles—Such exceptions can be recenciled, and are really not exceptions—Origin of term "Conservative"—Synonymous with "Tory"—First use of term "Liberal"—Modern meanings of term "Liberal" as various as numerous— [x] Definitions of "fifty reputed Liberals"—Mr. Broadhurst's definition—Lord Hartington's definition—Numerous other definitions—Numerous instances of confusion of meanings—Modern Radicalism—Origin of the term—Modern Radicalism synonymous with Socialism—Illustrations from Mr Chamberlain's speeches—Inconsistent utterances of that politician—Impossibility of deducing any clear or unanimously acknowledged meaning for any current political party-titles—Original meaning of term "Liberal"—Function of Liberal party in the future… - CHAPTER III. HISTORIC LIBERALISM.

A brief review of the principal struggles for civil liberty, from the Norman Conquest to the Reform Bill of 1832.

Man, a progressive animal—Ever striving for higher civilisation, i.e., more happiness—Historical instances of his missing the true course—Misery to society thus produced acts as a lesson to mankind—Politics a progressive science—Revolutions are the results of erroneous sociological calculations—To realise human progress, history must be viewed broadly, not in epochs only—Epochs mark the oscillations merely in the onward march—On the whole the movement is ever forward—Freedom the distinguishing point between Eastern and Western civilisations—Love of liberty traceable to climate—Advancement of the Western world, and stagnation of the Eastern, traceable to this element in society—Origin of government—Origin of feudal system—Theory of gradual growth of civil liberty from the Norman Conquest—Constant struggle for "equal opportunities"—History of Liberalism must be traced through "Whiggism" and "Roundheadism"—Charter of Henry I. the first limitation on the despotism established by the Conquest—Condition of English people after the Conquest—Division of property among the nobles—Absolute subjection of the English—Origin of Charter of Henry 1.—It marks the new relation between the people and the king—Magna Charta—Opinions of historians—How obtained from King John—Analysis of its provisions—All conferring additional liberty on the people——Petition of Right—Its origin—Its effect in conferring additional liberties—Habeas Corpus Act—Causes which led to it—Merely re-enactment of part of Magna Charta—What effect it had, in conferring additional liberty on citizens—The Revolution of 1688 - Produced by persistent abuses of royal prerogative—The immediate causes—The Cabal—Effect of the Revolution—Principles of the Declaration of Right—Effect on the people's liberties—Opinions of historians—American Independence—Causes which led to—Parliamentary struggle—Burke's and Chatham's efforts and warnings—The American War—Success of the colonists—Independence proclaimed—Catholic emancipation—Origin of the Reformation—Persecution of Catholics by English monarchs—The penal code—Catholic Association—Its suppression—Its reorganisation—The cry of "Emancipation—O'Connell's election to parliament—Passing of the measure—General conclusions from a review of the preceding reforms… - CHAPTER IV. MODERN LIBERALISM.

A brief review of the principal extensions of civil liberty, from the Reform Bill of 1832 to the Ballot Act of 1872.

The Reform Bill, one of the greatest Liberal victories in modern English history—Growth of Parliament—Early claims for the admission of "the people" to Parliamentary representation, by Burke and Wilkes—Condition of Parliamentary representation prior to the Reform Bill—Macaulay's criticism of the measure—Abolition of Slavery—Origin of the movement—Thomas Clarkson's efforts— [xi] Opposition of vested interests—George the Third's view of the institution—Passage of the measure—Corn-Laws abolition—History of the Corn-Laws over several centuries—Agitation for repeal—Really a trial of strength between Free-Trade and Protection Cobden's, Bright's, and Villiers' service in the cause—Immense sums of money collected in furtherance of the agitation—Division on the measure—Comments of Sir Erskine May, Buckle, and others—John Bright's testimony to the assistance of the Irish representatives—Sir Robert Peel's eulogy of Cobden—Subsequent comments of John Bright—The Chartist movement—Distinguishing features—Partly Liberal, partly Socialistic in its demands—Social discontent underlying the movement—Agitation for the measure—The "six points"—Influence of the French Revolution—Causes of its failure—Macaulay's criticism in Parliament—His prediction concerning Universal Suffrage—Jewish Disabilities—Previous history of the race in England—Their unchristian treatment—Repeated persecutions—First introduction of the measure—Macaulay's expressions of opinion in Parliament—Baron Rothschilds election, and refusal to take the oath—His forced withdrawal—Mr. David Salomon's election and forced withdrawal—Mr. Bright's views in 1853—Trades' Union Act of 1871—Early treatment of labouring classes—Legislative interference with wages, hours of labour, etc.—Trade associations regarded as illegal—Passing of the measure—Ballot Act of 1872—First advocates in 1705—Early interest in the question by Burke, Fox, Sheridan, and others—Controversy concerning the principle of the measure—Views of John Bright and Sir Erskine May—Numerous divisions on the annual motion concerning it—Review of the several Liberal movements treated of in the chapter… - CHAPTER V. THE PRINCIPLES OF TRUE LIBERALISM.

An attempt to define, in general terms, the sociological basis of government.

Politics really a science—Widespread ignorance of the fact—Various authorities in confirmation—Legislative failures—Proportion of abortive legislation—Happiness of humanity the fundamental aim of all good government—Man, the starting-point—Security of the person and of property man's first wants—Subject to those limitations, liberty for the individual the great aim—More necessary even in civilised communities—Without security no safety for life—Without security for property, no accumulation for the future—Without accumulation there is no leisure—Without leisure there is no civilisation—Cowen, Carlyle, Bright, and Burke on the blessings of liberty—Failure of Eastern nations for want of liberty—What is liberty?—Not absolute freedom—That is Anarchy—Limitations to be placed upon absolute freedom—Primary functions of a governing power—Double function in the present day—To rectify the past, and to provide for the future—Definition of true Liberalism—Growth of Liberalism in England—Definitions by "fifty reputed" Liberals—Reversal of true functions in present day—Tyranny of majorities—Principles of Liberalism defined by Mr. Gladstone, Mr. Stansfield, Professor Dicey, Léon Say, and others—Relative positions of Conservative and Liberal parties—Ideal of true Liberalism… - CHAPTER VI. SPURIOUS LIBERALISM—HISTORIC INSTANCES.

Differences in the causes which led to spurious Liberalism in historic times and in modern times—Abortive attempts to encourage agricultural interest in reign of George II.—Formerly government in hands of better educated classes who were ignorant of economic laws—Now that political economy known to most educated people, balance of government passed into hands of masses, who are equally ignorant of economic laws—Effect of Franchise Act of 1885—Prospects of wiser government in view of the extended franchise—Abortive attempts to regulate prices of bread in reign of Henry III.—Abortive attempts to regulate prices of wool; to stimulate woollen manufacture; to prohibit exportation of wool and iron; to reduce the price of labour; to concentrate English markets; to dictate prices of provisions—Restraints upon foreign merchants—Abortive attempts to [xii] regulate prices of corn; to prevent usury; to prevent exportation of money, plate, or bullion; to prevent exportation of horses; to regulate the prices of bows, to regulate prices of cloth and other goods; to prevent the manufacture of cloth by machinery; to prevent the manufacture by other than trained workmen—System of monoopolies introduced by Elizabeth—Their effects on commerce—Abortive attempt to stimulate Shrewsbury cotton industry—Consequent decline of the industry—Confessions of the advocates of the interference—Destructive effect on commerce of exclusive companies encouraged by James I.—Abortive attempts in the reign of George II. to regulate prices of corn—Exportation prohibited—Contrary effect—Attempt in reign of Edward III. to keep down the price of herrings—Contrary result—Attempts to fix the locality of manufactories—Interference with workmen's wages—Attempts to regulate price of roofing material and tilers' wages—Prohibition of workmen's combinations—Tyranny over the working-classes in reign of Edward VI.—Regulation of hours of labour—Interference as late as 1795—Alleged approval of Pitt and Fox—Treatment of Scotch miners—Statute of labourers—Legislative regulation of workmen's meals—Number and nature of courses—Regulations regarding wearing apparel—Summary of chapter… - CHAPTER VII. SOME INFIRMITIES OF DEMOCRATIC GOVERNMENT.

Some infirmities of democratic government—Misconceived legislation of historic times, resulting from ignorance of economic laws—Existing data now afforded for a more complete political science—Present position of political economy in modern education—Perfunctory study of the subject—Ignorance of the masses concerning it—Infinitesimal proportion of the people actually acquainted with the political science—Consequence of such a state of things—Balance of political power now in hands of those who ignore the existence of such a science—Chances now greatly in favour of the decisions of the people being erroneous—Injury liable to result therefrom—Injurious results already operating—Correctness of Macaulay's prediction concerning universal suffrage—Some difficulties of the political science - Sir Henry Maine on the antagonism between democratic opinion and scientific truth—Universal suffrage in Australian colonies—"Self" the test of legislation—Illustrations from Colonial Trades' Union Congress—Tendency to demoralisation of legislators—Illustrations of class selfishness from proceedings of English Trades' Union Congresses—Connivance by Mr. Gladstone and Mr. Chamberlain—Democracy in America—Inevitable effect of persistent resort to class legislation—De Tocqueville on American democracy—Aristotle on democracy—Belief in wisdom of majorities—Belief in justice of determinations of majorities—Presumption in favour of majorities being entire y erroneous in their conclusions on any subject—Effect on current legislation—Correcting influences afforded by the existing method of government by party—Late Rev. F. W. Robertson on majorities—Prevalence of political bribery of the masses—The Bishop of Peterborough on wisdom of majorities—Lord Beaconsfield on the embodiment of principles of liberty in form of permanence—Mill on the necessity for guarding individual freedom—Opinions of the masses concerning duties of government—Frederick Harrison's advice to the working classes on the choice of representatives—Statutes literally measured by thickness of the volume—Universal practice of ignoring remote consequences of legislative measures—Hasty and ill-digested legislation—Advice of Lord Hartington, Mr. Gladstone, and Mr. Bright, concerning blind belief in acts of parliament—Illustrations of the prevalent ignorance as to limit of functions—General results of past legislation of the spurious order—Prospects for the immediate future—Conservative influences operating in colonial communities… - CHAPTER VIII. SPURIOUS LIBERALISM—MODERN INSTANCES.

Theory of the growth of Liberalism—Test of Liberalism by the working-classes of the present day—Direction of present-day Liberalism directly opposite to that of former times—Modern tendency to experiment on society by visionary state-schemes—Manifesto of Liberty and Property Defence League—Mr. Gladstone [xiii] on modern tendency—Adam Smith's "Wealth of Nations" marks an epoch in economic knowledge—Slow progress of the truth of that writer's doctrines—Free trade and Protection criticised in connection with state functions—Opinions of Herbert Spencer, John Bright, The Times, Joseph Chamberlain—Some illustrations of remote effects of a protective policy—Connection of free trade doctrines with the principle of the division of labour—Bounties and their results—Illustrations from the sugar industry—Indirect effects of Protection in the woollen, leather, farming, opium, and timber industries—Attempt to use diplomatic and consular officials abroad for commercial purposes—Lord Rosebery's criticism—Factories Act in the colony of Victoria—Injury to property of manufacturers involved—Shops-closing acts—Their effect on property—Legislation on the "eight hours" system—Shipping legislation and its injurious results—Illustrations of legislative ignorance—Confessions of shipwreck committee concerning futility of legislative interference—Confession by Mr. Chamberlain on same subject—Sunday-closing measures; their futility—Local option advocates; their further demands—Poor Law legislation—Agricultural allotments scheme—Opinions of Lord Hartington, John Bright, W. E. Forster, Mr. Goschen—The rights of property and Bentham—The "greatest happiness" principle and Bentham—The caucus and Mr. Joseph Cowen—The caucus in America—Choice of a Liberal leader by means of the caucus—Mr. Chamberlain and the caucus—Burke's standard of political independence—Liberalism, and liberality with state moneys—Employers' Liability Act; attempted extension—Socialist demands—Liberal statesmen and modern differences of opinion—Municipal socialism; its dangers—Increased functions of English municipalities—Socialism at St. Stephens in 1886—Increasing burdens of legislatures—Experimental legislation—Its dangers—Mr. Justice Kent's opinion—Remote effects—Summary… - CHAPTER IX. PRACTICAL APPLICATION OF THE PRINCIPLES OF TRUE LIBERALISM.

Necessity for demonstrating capabilities for practical application of any theory of legislation—Laissez faire; its real and literal meanings distinguished—Abuse of the reductio ad absurdum—Laissez faire frequently interpreted by its opponents as synonymous with Anarchy—Differences of opinion as to the point of limitation to human liberty—Effects of recognising no limit to state functions—Necessity for unanimity as to where that limit should be placed—Self-interest, the motive power of society—Self-interest should be subjected to the minimum of limitation, compatible with equal opportunities—Liberty, the true object of Government—Egoism and altruism alike founded on self-interest—The real difference is in the effect on society, the source being the same—Importance of regarding remote effects of legislation—Their non-recognition by the average legislator—Socialists and Individualists, the party-titles of the future—Fundamental misconception at the root of present social discontent—Present equality of all before the law—Point of divergence between Socialists and Individualists or true Liberals—Normal condition of man in primitive society—Effect of division of labour on production—Normal condition in civilised society, that of hard work—Capitalist class possess no privileges—Their domain an open field to all men—Visionary schemes for levelling up society—Wealth in one citizen as an obstacle to the individual freedom of others—Differences of opinion as to possibility of fixing a definite limit to state functions—Two theories of rights—Natural rights curtailed by the social contract—Natural rights abolished, and fresh rights conferred and secured by the law—Disciples of the two theories—Blackstone—Prof. Stanley Jevons—Bentham—Austin—Burke—Locke—Mr. Herbert Spencer—Impracticability of the former theory—Right to ignore the state—Human infirmities standing in the way of ideal legislation—Want of acknowledged limitation to state functions attributable to the different theories concerning rights—History of English law shows security to property and to the person to have been the first objects of government—Blackstone's classification of rights—Objections to rigid rules for legislation—Three fundamental principles—How applied—Burden of proof thrown on advocates of any measure subversive of those principles—Poor Laws—Confession of Poor Law Commissioners—Conclusions for and against the system—Balance of arguments favour continuance in communities where already established—Needful limitations—State education—Conclusions respecting true [xiv] functions of the state—Housing of the Poor—Radical arguments in favour—Conclusions against the proposal—Unemployed—Increasing resort to the practice of state assistance—Objections—Payment of members—Original object—Radical arguments—Grounds for objection—Land Nationalisation—Alleged advantages from the system examined—Conclusions—Public Works—Allowable departures from the general principle—State railways—Effect on taxpayers—Arguments for their being undertaken in young communities examined—Gas and water supply—Telegraph and telephone systems—Colonial railway results—Municipal undertakings—State monopolies condemned—Drainage, sewage, paying, lighting—Allotments scheme—Shipping legislation—Injury to British shipping compared with that of foreign countries—Steam boilers—Contracts—Shops closing—Factories Acts—Protection—Sunday closing—Summary of chapter… - CHAPTER X. SOCIALISM AND COMMUNISM.

A short enquiry concerning the principal theories and practical experiments of ancient and modern times, in the search for an ideal form of commonwealth.

Bearing of the chapter on remainder of the work—Relative attitudes of Individualism and Socialism explained—Effect of the latter on human motives—Present constitution of the English legislature—Prospects of scientific legislation—Drift of modern public opinion—Signs of the approaching conflict—French anarchists—Knights of Labour in America—America's reception of John Most, the expelled revolutionist—Socialist Press of New York—London Socialist outbreaks—Mr. Chamberlain's doctrines—The Radical programme—M. de Laveleye's "Primitive Property"—His doctrines—Mill's earlier observations on Socialism and Communism—Aristotle on community of property—Effect on the virtues of liberality and kindness—Christian Socialism—Causes which led to it—Commonwealth of Love—The Poor Saints—The voluntary element prominent in all early experiments—Middle-Ages Communism—Brothers of the Common Lot—Brothers of the Common Life—Apostolici—The Waldenses and the Minorities—The Lollards—The Taborites—The Cathari, Apostolicals, Fratricelli, Belguins, Albigenses, and Hussites—The Moravian Brotherhood—The United Brethren—The Hernhuters and the Hutterites—The Unitas Fratrum—Christian Republic of Paraguay—M. de Laveleye's "Primitive Property"—Village communities in Russia—The Russian Mir—M. de Laveleye's reasoning examined—Village communities in Java and India—The Allmends of Switzerland—Social inequalities under the system—Unfair comparisons—The German Mark—Agrarian system of the Irish Celts—Agrarian communities among the Arabs and other nations—The French Revolution—Its effect in producing a crop of social schemes—Element of poetry in almost all ideal theories—Modern definitions of Socialism and Communism—Saint-Simon—His theories—His disciples—François Babœuf and his theories—Charles Fourier and his theories—Ettiene Cabet and his theories—Proudhon and his theories—Karl Rodbertus and his theories—Louis Blanc and his theories—Karl Marx and his theories—Ferdinand Lassalle and his theories—Robert Owen; his theories and experiments—American Socialism—Advantages of experiment over theory—The Shakers—The Amana Community—The Harmony Society—The Separatists of Zoar—The Perfectionists of Oneida—The Aurora and Bethel Communes—The Icarians—Unanimity of Coramunist leaders as to the causes of failure—Mill's later opinions on Communism and Socialism—Review of the whole work—The outlook and its dangers—The coming struggle…

"It is of the utmost importance that all reflecting persons should take into early consideration what these popular political creeds are likely to be, and that every single article of them should be brought under the fullest light of investigation and discussion; so that, if possible, when the time shall be ripe, whatever is right in them may be adopted, and what is wrong rejected, by general consent; and that, instead of a hostile conflict, physical or only moral, between the old and the new, the best parts of both may be combined in a renovated social fabric."

J. S. MILL ("Chapters on Socialism").

[i]

PREFACE.↩

THE following pages have been written for the purpose of tracing the gradual but sure growth of our civil liberty, from historic times, downward to our own day, and of investigating the great principles which inspired our ancestors, in their efforts to secure that great inheritance to us, their posterity. A further object that I have had in view—and perhaps this latter may be regarded as the more important—is to show the symptoms, which are gathering fast and thick around us, of a new order of things—of, in fact, a distinct surrender of the traditional safeguards of that civil liberty—the "cornerstone" of our great and deservedly enviable constitution.

I have endeavoured to prove that the invaluable principle of individual freedom—which, from the Norman Conquest downward, fired the most noble-minded of our ancestors to rebel against the tyranny of those who won, or inherited, the rights of that conquest—is in imminent danger of being lost to us, at the very hour of its consummation. And I have, I think, further demonstrated that so sure as we depart from those traditional lines, in the endeavour to realise a condition of society, which can only exist in the imagination—viz., a community of people, enjoying equal social conditions,—we shall, when it is too late, find that we have lost the substance, in grasping at the shadow.

In order to realise the above perhaps somewhat ambitious purposes, I have enumerated instances to show that the term "Liberalism," which in its original and true interpretation was [ii] synonymous with "freedom," has, in our own day, lost that genuine meaning, and is, instead, carrying with it, to the minds of most men, other and quite erroneous significations; and further, that political party-titles, generally, have now ceased to carry with them any clear conception of political principles: having become so inextricably mixed and confused in the meanings which they convey, that it is impossible to deduce, from the fact of their being professed by any individual, any distinct conclusion as to that individual's political creed.

I have then shown that, from the earliest times in the regular history of England, the principle of individual freedom was the one which, paramount to all others, characterised the greatest of England's reforms; but that, in the present day, that time-honoured principle appears to have lost its charm, and the political title "Liberalism," which previously served as its synonym, is being gradually perverted to the service of a cause, which must, sooner or later, be wholly destructive of that very liberty, from which it derived its existence as a political term.

I have also, I believe, been able to demonstrate that this tendency (though the fact is not generally recognised) is clearly in the direction of those conditions or forms of society, known as "Socialism" and "Communism;" and, finally, I have, I think, given sufficient proof, from unexceptionable authorities, of the fact that all practical attempts at such conditions of society, have, whenever and wherever tried, hopelessly failed in their results; and, instead of lifting the lowest stratum of society to the level of the highest, (as was anticipated), or even approximating to it, dragged the whole fabric down to the dead level of a primitive and uncultured existence, sapped the enterprise and independence, as well as stifled the higher faculties of all who have helped to constitute such communities, and ended in placing such as conformed to their principles at the mercy of nature, with [iii] all its uncertainties of season, and disappointments of production.

I venture to think that there is no part of the civilised world, in which the term "Liberalism" has been more constantly, or with more confidence, misused than in the English colonies, and more especially in the colony of Victoria. Political thought has there been developed and sharpened to an extent, which has scarcely been equalled, certainly not surpassed, in any part of the world—even in the United States; so that, in fact, it affords to the political students of other and older countries, who may consider it worthy of their attention, an invaluable political laboratory for the purpose of judging the merits of many "advanced" legislative experiments. This identical view I expressed at some length in The Times, as far back as 1877.

Bearing the foregoing facts in view, I have drawn a great number and variety of my illustrations from the legislative and other public proceedings of the particular colony mentioned.

Side by side with this unusual development of political activity and intelligence, which is specially noticeable in that colony, there has unfortunately grown up a most serious misconception or misrepresentation, as to the true meaning of the political term, concerning which I have more particularly treated; and there is distinctly apparent—there, as in Great Britain—all the symptoms of a return to "class" legislation of the most despotic character; not, as of old, in favour of the wealthy and aristocratic orders, but in the opposite direction, of conferring positive benefits upon the working classes—that is to say, the manual working classes—at the expense of the remainder of the community. Indeed the extreme Radical party of Great Britain have already acknowledged that "there is scarcely an organic change which has found a place in the programme of advanced Liberalism, that has not been accepted, and voluntarily introduced…at the Antipodes."

[iv]

One of the most unfortunate circumstances in connection with colonial politics is the disinclination on the part of the wealthier and better educated classes to enter into competition with the omnipromising political hack, for the honour of a seat in parliament. That most constituencies are at the mercy of those candidates who promise most of what does not belong to them, is indeed too true; but there are, one is happy to be able to say, many constituencies in which political morality has not sunk so low as to necessitate a candidate substituting flattery and transparent bribes, for home truths and sound political doctrine. Those constituencies are, however, comparatively few in number. That fact, coupled with the thoroughly unscientific tone of current politics, has, in most of the colonies, left the field open to a class of men, by no means representative of the average education, or of the average political knowledge. It is to be regretted, however, that the wealthier and better-educated classes do not make a greater sacrifice, on patriotic grounds, and thus assist to raise the tone of an institution which they are always too ready to condemn.

Since commencing my investigations, which have extended over many months, and have been carried on during the leisure hours left to me out of an otherwise extremely busy life, I have been brought into contact with a mass of material, evidencing the patriotic "footprints" of a body of men, now doing good work in England, under the title of "The Liberty and Property Defence League." This League has been formed for the purpose of "resisting over-legislation, for maintaining Individualism as opposed to Socialism—entirely irrespective of party politics."

To have become acquainted with the efforts of such an organisation, and to have learnt how great is the success which has attended its efforts, has considerably encouraged my own labours.

[v]

I find that, during the last two years, the League printed 54,250 pamphlets and 39,300 leaflets, "pointing out, in general and particular, the growing tendency to substitute Government regulation, in place of individual management and enterprise, in all branches of industry; and demonstrating the paralysing effect of this kind of legislation upon national development."

I find, further, that "these publications have been distributed among over 500 of the chief London and provincial papers, and among members of both Houses of Parliament and the general public;" and that "400 lectures and addresses have been delivered by representatives of the League, before working-class audiences, in London and elsewhere." The annual report for 1884 states that, "reckoning together those who have thus joined through their respective societies or companies" with which the League is associated, in addition to "those who have joined individually, it comprises over 300,000 members."

The council of the League embraces the names of many eminent men, including those of Lord Justice Bramwell, the Earl of Wemyss, Lord Penzance, and the Earl of Pembroke; and it would seem that scarcely any single parliamentary measure is allowed to put in an appearance, in either branch of the British legislature, without being subjected to the most searching examination and dissection, at the hands of that council.

Such legislation as is considered contrary to the principles of the League—which are non-party—is opposed in every possible way; and no money or other means appear to be spared, to prevent such legislation being placed upon the statute-book. The efforts of the League seem, too, so far as they have gone, to have been extraordinarily successful.

I may add that my own investigations were commenced with the simple object of delivering a short lecture; but the materials, which I found necessary to collect, soon grew to [vi] the proportions of a volume, which I have now completed, in the hope that others, who are sufficiently interested to peruse it, may be saved the same research and classification of principles, which are necessary to a complete understanding and grasp of the subject. As far as originality is concerned, I claim no merit, except in the mere arrangement of my work; but the labour has, notwithstanding, been great, and not always encouraging. Indeed, in almost every position which I have taken up in the investigation of my subject, I have, as will be seen, fortified myself with the opinions of the greatest among those who have sounded the depths of political philosophy. Any exception, therefore, which may be taken to the doctrines which I have merely reproduced, will involve a joining of issue with many of the most profound political thinkers of ancient and modern times.

I owe an explanation—perhaps an apology—to many of the authors from whose writings I have thus drawn my numerous quotations, for the constant rendering of their words in italics. In almost every case throughout the work the italicising is my own. I am fully aware of the danger of detracting from the force of language, by the too frequent resort to that aid to emphasis. My only excuse is the unusual necessity for clear distinctions, in the terms and phrases employed.

No apology is, I think, needed for my venturing to draw public attention to the subject itself, with which I have thus dealt. That it is sufficiently important, there can be no possible doubt; and that it is not a settled question, has been fully admitted by no less an authority than Mill, who says: "One of the most disputed questions, both in political science and in practical statesmanship, at this particular period, relates to the proper limits of the functions and agency of governments." And he adds that it is, as a discussion, "more likely to increase than diminish in interest." Indeed, it has at various [vii] times been a matter of considerable surprise to me, how little the whole subject seems to have been investigated, or even considered, not merely by the ordinary political delegate (popularly known as a politician), but by men, educated in history, and professing to feel an interest in the philosophy which underlies it.

If, in the compilation of the thoughts of others, I should succeed in directing the attention of some of my fellow-men to the great political and social danger which is now impending, and thus bring about a clearer and more correct recognition of the traditional principles which I have ventured to champion, I shall be quite satisfied with the result of my labours.

I am quite conscious of the unpopularity which much of what I have written is calculated to draw upon me from the working-classes, as also from mere work-a-day politicians, concerning whose knowledge of the political science I have certainly not spoken in flattering terms. To have so written has, however, required the more courage, inasmuch as I am desirous, and even sanguine, of yet taking a further and more prominent part in practical politics. But I have ventured to say what I have said, because I believe it to be true; and I have sufficient faith in the spirit of manliness and fair play, which, at least, has always characterised our race, to hope that the unpalatableness of my remarks may be forgiven, on the score of their sincerity and good intent.

June, 1887.

[xx]

"The time has come when, if this country is to be preserved from serious perils, honest men must enquire, not what any one with whom they are invited to co-operate may call himself, but what he is, and what the political objects are for which he would use the power if he had it."

LORD SELBORNE (Contemporary Review), March, 1887.

[1]

CHAPTER I.↩

"LIBERALISM" AND OTHER CURRENT POLITICAL PARTY-TITLES—THEIR UNCERTAIN SIGNIFICATION.

"A group of words, phrases, maxims, and general propositions, which have their root in political theories, not indeed far removed from us by distance of time, but as much forgotten by the mass of mankind, as if they had belonged to the remotest antiquity."—SIR HENRY MAINE, Popular Government.

MANY and various circumstances have, of late, rendered it almost impossible to obtain anything like universally accepted definitions of the principal terms of political classification, which are in general use among the present generation of English-speaking communities. Great Britain has lately passed through the ordeal of two general elections, occurring in quick succession, and the kaleidoscopic results of those elections, among political parties, and among political leaders, have rendered that uncertainty of signification even more striking than it was before. In some of the British colonies, as might have been expected, a tolerably widespread use has been made of the political arguments and theories which have done so much service in the older community; and this especially applies in the case of the colony of Victoria, to the legislation of which, I shall, in the following pages, frequently refer for illustrations of my arguments.

It does not seem to be thought, or at least very clearly recognised, in any of such colonies, that those arguments [2] and theories, though originally capable of ready and consistent application in the case of Great Britain, which has a history, which has traditions, which possesses a less "advanced" condition of society, as well as institutions of a much less democratic order, should nevertheless have little or no bearing upon the affairs of younger communities, in which the whole circumstances of the people are upon a different footing. Strange to say, this anomaly seems to have been less realised in the colony of Victoria than in any other of such younger communities, notwithstanding the fact that, in it, there is no established church; that, in it, land (the chief subject of modern political theories) can be purchased from the State, at a price which would seem ridiculous to an English agricultural labourer; and that, in it, such restrictive customs upon land transfer and land disintegration, as primogeniture and entail, do not exist.

There is, I venture to think, no community in the world, not excepting the United States, in which the terms of political classification, now current in Great Britain, have less real application, than in the colony of Victoria, where every man already has an equal voice in matters political, irrespective of wealth, social status, or even common intelligence—where, in short (to use the words of the "Liberal" Press), "the working classes really run the political machine, where there is exactly the same freedom to rich and poor alike, and where the rich are for the most part recruited from the ranks of the poor, and have become rich by the labour of their own hands."

However, since Anglo-colonials are, for the most part originally of Great Britain, it is but natural that they, or their parents before them, should have brought with them the traditional political terms of the mother country, though never so inapplicable. As consequences, however, of so doing, many persons, in the younger communities, have become involved in a maze of needless bewilderment, and [3] have filled their minds with, what Sir Henry Maine has aptly described, as "a group of words, phrases, maxims, and general propositions, which have their root in political theories, not indeed far removed from us by distance of time, but as much forgotten by the mass of mankind as if they had belonged to the remotest antiquity." [1] It is my purpose, in this chapter, to show, first, that the political party-titles, which are upon everybody's lips in Great Britain in the present day, and in comparatively frequent use in the Australian colonies, cannot have, according to their proper interpretation, any application to the latter; secondly, that even if they were capable of such an application, the meanings which are being attached to them are wholly incorrect and misleading. In the particular colony, from which I have stated my intention to draw many of my illustrations, there is a powerful section of the Press, which designates itself "Liberal." That section has hitherto assumed the function of classifying the various candidates offering themselves for Parliamentary election, and of promising success, or predicting failure, in the case of each of them, according to that classification. In the performance of this self-imposed duty, it has not always been content to adopt the political terms applied by the candidates to themselves, who should certainly be best qualified to speak concerning their own principles, but it has frequently denied, in a very positive way, their right to be placed in the category which they had themselves chosen. The reasons given by this section of the Press for these somewhat haphazard classifications have been anything but noteworthy for their soundness, and the confusion of meanings, which other circumstances have of late combined to produce, regarding the meanings of such terms as "Liberal" and "Conservative," has been intensified rather than cleared up by these [4] bewildering attempts at local application. An illustration of this misuse of terms is afforded in the fact that, a few months previous to the time at which I am writing, the section of the Press in question strongly advocated the return of a particular candidate to Parliament, upon the ground that he was "a Liberal and a Protectionist," and at the same time recommended the rejection of his opponent, upon the ground of his being "a Conservative and a Freetrader."

Now, it is about as clear that one man cannot possibly be a "Liberal and a Protectionist," at one and the same time, as it is that a sceptic, in theological matters, cannot be orthodox.

A mere glance at the history of the Corn Laws Repeal will show this conclusively; for that movement (the greatest of all battle-grounds for the principles of Free Trade and Protection), will prove that that repeal, but for the constant and persistent opposition of the Tory party in the House of Commons, and the consequent establishment of Free-trade, would have taken place some years earlier than it really did. It will show, further, that, in "all the divisions" upon the repeal of those laws, "the Government had the aid of nearly the whole of the Liberals, the opposition being almost entirely Tory," [2] and that, in the final division, 202 Liberals voted for the repeal, and only 8 against it, while 208 Conservatives voted against the repeal, and only 102 for the maintenance of the old protective policy. [3] Mr. Harris, in the work from which I quote, observes that "It was in Free Trade alone that Palmerston was a Liberal." Quite apart, however, from the historical aspect of the movement, it is apparent that the principle of Protection is diametrically opposed to the spirit of "Liberalism," inasmuch as the former depends upon the [5] imposition of an artificial restriction on importation, having the effect of curtailing the liberties of such citizens as desire to purchase, abroad, the particular class of goods so protected, in order that a positive benefit may be conferred upon a particular section of the community. The latter school of politics, on the other hand, depends, for the very derivation and ordinary meaning of its title, upon the principle of "freedom for the individual."

If, by the term "Liberalism," it is intended to convey that the individual should be made more free by the removal of class restrictions, —that being, I contend, the fundamental principle of the school— then "Protection," as a policy, is wholly retrogressive, and contrary to the meaning of that term; and it is therefore absolutely paradoxical to speak of the two principles involved in the terms "Liberalism" and "Protection" being professed by one and the same person, at the same time. This single illustration is of great importance, when considered in connection with the colony from which it is taken. Victoria has consistently maintained for upwards of twenty years, a policy of substantial protection to local industries; and, throughout that period, the "Liberal" section of the Press has, as consistently, claimed that policy as coming unmistakably within the meaning of its party-title. So persistently, too, has this been contended for, that the bulk of the working classes of the colony have come, at last, to regard "Liberalism" and "Protection" as almost synonymous.

It has often been said that, if a falsehood is only repeated often enough, the teller of the story, in which the falsehood is involved, will, in time, come himself to believe in its truth. The above circumstance affords an illustration in which the hearers also have become convinced by mere repetition.

Such an application of the term, as that above mentioned, points to a most marked misinterpretation, intentional or [6] otherwise, of the title "Liberalism," by the very section of the Press, which professes to deal with public matters from its standpoint, and it is a noteworthy fact, as evidencing the absence of any deep-seated differences in political opinion, that throughout the last one or two general elections in Victoria, the terms "Liberal" and "Conservative" were the only two political party-titles used with any degree of frequency. In Great Britain, about the same period, a much larger number were brought into service, with which however, we are not now concerned.

If one looks for light regarding the local application of this term in the colony referred to, one fails to find it in the occasional definitions which are incidentally afforded. They all point to a sort of hotch-potch of ideas, and it is impossible even to get a clear meaning to attach to the term, even though one might be satisfied to overlook the fact of such a meaning being erroneous.

I have mentioned the "Liberal" Press of Victoria, or rather that section of the Press which professes "Liberal" principles, because of the prominent part which it assumes, and is, in fact, allowed to take in the settlement of the public affairs of that colony; and, further, because it exercises, in matters political, an immense amount of influence over the masses, which it has, unfortunately, and whatever may have been its motives, more often than not, so directed, as to intensify rather than allay any class animosity, which has arisen from other causes.

It is moreover to the same source, more particularly, that is owed the constant and persistent employment of the term, as well as the erroneous meaning which has come to be attached to it among the masses of the people in that particular colony.

That this constant use, or rather misuse, has had an appreciable effect upon party divisions in the past, whether inside or outside Parliament, there can be no doubt; but [7] that effect has not, I venture to think, arisen so much from the use of any sound argument in favour of its application, as to the facts that the term carries with it, in most minds, many favoured associations; and that the assertions regarding its applicability have been repeated for so many years, —an influence, sufficient in itself, to carry conviction to the minds of the majority of one's fellow-beings.

One is much inclined to look for the motive for this really injurious practice of labelling undesirable things with desirable names: of advocating undesirable movements by attaching to them names, which carry conviction by their very associations. It is of course necessary to remember, and it would be well if the masses would only do so, that newspaper proprietors, like merchants and manufacturers, have to make their ventures pay; and just as the merchant and the manufacturer learn to import or make an article which suits the public fancy, and thereby meets with a ready sale, so the newspaper proprietor, unless actuated by purely philanthropical motives (which can scarcely be expected) deems it most advantageous to give to his subscribers matter, which is calculated to please, rather than to instruct. The Press, however, is by no means the only source of error in this particular; for I find colonial politicians, of comparative eminence, using the term in question, in senses wholly foreign to its original and correct signification, without, moreover, provoking any comment from their party associates.

Within a very short period of the time at which I write, I find a prominent "Liberal" member of the Victorian Legislature, characterising an Act of Parliament, for irrigation purposes, as "a pawn-broker's bill." "It was" he said" a mean conservative measure; and the duty of the House was to liberalise it, for there was," he added, "no liberality in it."

[8]

This remarkable utterance points to a very popular interpretation of the term among many colonial politicians. Some time, indeed, before this, a Minister of the Crown, of the same colony, in speaking before his constituents concerning the same measure, then in prospect only, boasted that it was a proposal "which for liberality and justice could neither be equalled nor surpassed."

He then went on to say that the government, of which he was a member, would have power to "postpone the payment of interest" on moneys advanced to the farming class for purposes of irrigation works. This was a course, which, according to the popular interpretation alluded to, would have fully entitled his ministry to the title "Liberal," though it could be so applied only in the sense of a government being "liberal" to one section of the community, at the expense of the whole population, interested in the general revenue.

On another occasion, I find an ex-Minister of the Crown, also in the same colony, deprecating an alliance between the "Liberals" and the "Conservatives" on the ground that there was a sufficient number of the former to constitute what he termed a "straight" Liberal government.

On being asked by a fellow-member what he meant by a conservative, he replied, "a conservative is a man who looks after number one." Here again we find the same misconception at work—the word "Liberal" being interpreted as meaning one who is given to liberality with the public revenue, and in favour of class interests—the "conservative" one who is opposed to such liberality.

I might quote many like instances, in the different colonies, to show that the true meaning of this term is a matter which gives little concern to the ordinary run of politicians, though meanwhile general elections are allowed to turn on it.

The result of these numerous misinterpretations which have been placed upon such political terms, and more [9] especially upon the particular one of which I am treating, by many public men, as also by an important and influential section of the Press, has been to lead to a complete neglect of the true principles which they respectively represent. And that neglect having continued, other and spurious meanings have been meanwhile attached to them by the masses of the people. It is of course a fact which everyone who has studied history must know, that all the great reforms, which have taken place during the last eight centuries of English history, have had the effect of conferring on "the people" (as distinguished from Royalty, and the aristocratic and monied classes) a large amount of individual freedom. As a result of that freedom, the people have been enabled to enjoy a great many more opportunities for worldly comfort and social advantages. They have been enabled to take part in political matters, and thus secured many liberties which formerly they were denied; and they have been enabled to combine among themselves, without fear of punishment, and thus secured higher wages, and a larger share of the comforts of life. All this, as I shall show hereafter, has been the combined results of many "Liberal" movements. On account of the absolute usurpation of power and privilege, by Royalty and by the aristocracy, at the time of the Norman Conquest, the progress of "Liberalism" has produced a long, uninterrupted, and concurrent flow of concessions to the people's liberty. So long has this "horn of plenty" continued to shower these concessions and consequent advantages upon "the people," that the working classes have been brought to believe no action of the Legislature can possibly be entitled to be placed in the category of "Liberal" measures, unless it is actually accompanied by some positive advantages for themselves. Thus, from the very nature of England's early history, these benefits have invariably flowed from "Liberal" legislation; but, as I shall, I think, hereafter show, a time has been reached in that [10] history, (whether of England itself or of the English speaking race in our own colonies) when privileges of almost every kind have been abolished, so that every man, be he rich or poor, now enjoys "equal opportunities" with the possessor of the "bluest blood," or of the largest bank balance.

That being so, the (what I would term) aggressive function of Liberalism has been exhausted, and, with certain minor exceptions, it only remains for it to guard over the equal liberties of citizens generally, with a view to their preservation. This I regard as the proper function of Liberalism in the present day. The masses of the people, however, are still looking for positive benefits, and their production or non-production by any legislative measure is still made the test of its being the "genuine article." The masses, too, are prepared to apply the term, and to acquiesce in its being applied by others, to any measure which promises to confer some advantages upon themselves as a class, even, there is reason to fear, though such a measure may, on the very face of it, involve treatment, injurious to the interests of the remainder of the community.

This I regard as the cardinal error of modern politics, and modern legislation; and, as a consequence of this error being so widely entertained, there are, I venture to think, becoming apparent, tolerably clear symptoms of a class struggle through the medium of the legislature, which must end injuriously to our best civil interests.

In the colony of Victoria, public life, has been greatly demoralised by this misconception. A candidate for parliament presents himself before his would-be constituents, and readily promises to give them anything they may want, and to secure an act of parliament for any and every desire to which they may think fit to give expression. He readily undertakes to ignore the rich man, and do everything for the poor one, make life easy—a paradise in fact—for the latter, and punish the former with [11] more taxation. Such a candidate is at once held up for the admiration and approval of the electors as a "Liberal." Another aspirant, having some regard for his principles, ventures to say that he disapproves of class legislation; that he will do nothing calculated to unduly curtail the liberties of his fellow citizens, for the benefit of a section of the community; that he considers the good government of the country of more importance than selfish political party divisions, founded upon terms which have no meaning or application in the community. That man is immediately, and with as little meaning or reason, marked "Conservative," and, as likely as not favoured with a few graceful epithets, directed at his motives.

This constant application, or misapplication of these two terms, and the "damnable iteration" to which they have been subjected, have given the particular words certain fixed signification, alike erroneous and dangerous; and it certainly seems as if the time had long since arrived when some effort should be made, if not to restore to them the meanings and bearings which they originally and properly conveyed, at least to endeavour to bring about a clearer and more correct understanding of the new significations which are to be attached to them in the future.

Let us turn now more immediately to the politics of Great Britain, and we shall find that though the institutions of that older community, would, with some better show of consistency, admit of the application of such party-titles to its national politics, nevertheless they are in the present day, even there, being perverted to significations, altogether foreign to those which were originally intended. The last two general elections in Great Britain may be said to have attracted more attention to the meanings of the terms "Liberal" and "Conservative" than perhaps they have ever previously received, and a consideration of the political incidents of the last two or three years, over which period [12] the change has been gradually taking place, is capable of affording abundant matter for reflection on the subject with which I am dealing.

Mr. Joseph Chamberlain's, or perhaps, it would be more correct to say, Mr. Jesse Collings' startling proposals, with which every student of current politics is familiar, seem to have necessitated the reconsideration by many old and experienced politicians of the very first principles of the political policy which they were being assumed to profess. This arose from their continuing to class themselves under political party names, to which a new generation, or the leaders of that generation, were endeavouring to attach significations alike novel and historically incorrect. Those particular proposals, which are of the most unmistakably socialistic character, were then, and have been since claimed to come, whether considered from an analytical or historical standpoint, within the definition of the term "Liberalism;" and so frequently and persistently has this been contended for, that many people, who had previously gloried in their connection with the school of politics, which that term originally designated, have been forced, in order to avoid misconception as to their principles, to either use some qualifying phrase, such as "Moderate Liberalism," to better define their political creed, or to actually go over to the Conservative party. This influence, acting upon a good many minds, already more or less near the border-land of the respective party domains, has produced within the last one or two years only, some peculiarly kaleidoscopic effects in the political ranks of Great Britain. Such sound Liberals, even as Lord Hartington, Mr. Goschen, and others, were constrained, for the time being, to leave their political friends in the division on the question referred to—that of the allottments for agricultural labourers; claimed, as I have said, to come properly within the lines of "Liberalism." The division to which I here refer, was that which took place [13] upon an amendment to the reply to the Queen's Speech, immediately after the general election of 1885, and which was moved by Mr. Jesse Collings. The amendment turned upon the question of adding to the reply to the Queen's Speech an expression favourable to the allottments proposals. The division resulted in the defeat of the Tory party; but the proposals were strongly denounced by Lord Hartington and Mr. Goschen, as also by Mr. Bright and Mr. Joseph Cowen, all being Liberals of the soundest order. Ere these pages leave my hands we are in receipt of the astounding news that this identical scheme has been adopted by the Conservative Government, now in power, and that there is every prospect of its being acquiesced in by the "rank and file" of that party. A more significant event even than that is the acceptance by Mr. Goschen (an admittedly sound Liberal) of the leadership, in the House of Commons, of the Conservative party. Such events as these must indeed be conclusive, as showing that party titles have entirely lost their meaning, and really involve no principles whatever. The measure referred to originated with the most "advanced" wing of the Radical party, was denounced by the most moderate of the Liberals, and within a few months is included in the Tory policy! The Times, of 22nd October, 1886, observes—"It is right that the Tory party should become a moderate Liberal party, just as after the first Reform Bill, it became a Conservative party; but we doubt if either Conservative, or Unionist's Liberals will be content to see it transformed into a Radical party, pure and simple."

One of the most singular instances which I can mention, of the changed significations which are gradually being attached to such terms, is afforded by a quotation from a late publication, called "The Gladstone Parliament." "Most of the measures," says the writer, "which Mr. Bright advocated, have been passed, and Mr. Bright has become a Conservative [14] to all intents and purposes." I leave to my readers to determine whether it is not more likely that the term "Conservative" has undergone a great change of meaning than that a great and ever consistent "Liberal" statesman, such as Mr. Bright, has changed his political principles. Almost the same thing has been said of Mr. Goschen, who is probably one of the most steadfast and consistent Liberals of his generation. Indeed, the "Liberal Press" of the colony of Victoria has paid a high tribute to the ability and constancy to principle of that statesman. "He is," it has said, "in the very front rank of English Liberals, and has proved himself a sterling administrator. He has always been of a scholarly temperament, a man thoroughly conversant with first principles, and indisposed to sacrifice abstract right to expediency." "Yet," confesses the same journal, "he might count almost anywhere on splitting the Liberal vote, and on getting the solid vote of the Conservatives." This is afterwards accounted for on the ground that (among other things), "he has often voted over the heads of the multitude," and "never perfectly mastered the clap-trap and party cries of the British Philistine."

The fact is, as will be admitted by all who know anything of the man's career, he is an absolutely consistent Liberal who well knows the meaning of his party title, and the fundamental principles upon which it is founded, while the average elector, who contributed to his late rejection, is quite ignorant of that meaning or those principles.

Mr. Chamberlain lately said of Mr. Goschen, "Although he sits behind us he is very far behind, and I think that under a system of scientific classification he is rather to be described as a 'moderate Conservative' than as a 'Liberal.'"

The fact is the meanings of these terms are fast changing, and they themselves are being perverted to denote principles which were never contemplated either in their etymology, or by their originators. The following quotation from the [15] Times of 26th February, 1885, is peculiarly confirmatory of such a process. Speaking of the growing tendency to over-legislation in our own day that journal says, "This readiness to invoke the interference of the State between man and man, and to control by legislation, the liberties of individuals and the rights of property, is rapidly modifying the character of Liberal principles, as they were understood, even a few years ago." Elsewhere the same journal says, "The march of time has obliterated most of the distinctions between Whig and Tory. People are beginning to enquire seriously what a political party means." And again, it speaks of "The party badges which have long since ceased to denote any real difference of sentiment."

On 4th March, 1886, the following passage occurs in a leader of the same influential organ, "Our actual party names have become useless and even ridiculous. It is absurd to speak of a Liberal, when no man can tell whether it means Mr. Gladstone or Sir Henry James. It is absurd to speak of a Radical, when the word may denote either a man like Mr. Chamberlain, or a man like Mr. Morley…. It is ridiculous to maintain a distinction between moderate Liberals and moderate Conservatives, which no man can define or grasp, and which breaks down every test that can be applied by the practical politics of the day."

A much later proof of the want of clearness and certainty in the meaning of these two principle political terms is afforded by the division upon Mr. Gladstone's Home Rule Bill. On that occasion we find some of the most prominent and eminent Liberals of the day—men like Lord Hartington, Mr. Bright, Mr. Goschen, and Mr. Trevelyan, as well as more "advanced" politicians of the Radical school, such as Mr. Chamberlain, completely breaking away from their party, on grounds of absolute principle. We find the difference of opinion so deeply seated, that at the general [16] election which followed the rejection of that measure, a large and formidable section of the Liberal and Radical parties actually allied themselves with the Tories, in their determination to vindicate, what they deemed to be, a vital principle of their school. Indeed, it is in the highest degree questionable whether the breach, which has thus been brought about, will be thoroughly healed for a considerable time, so strong has been the feeling, and so deeply rooted the differences of principle which have been thereby developed.

Who indeed could now say, under such circumstances, whether the Home Rule principle is or is not properly within the lines of Liberalism? Mr. Gladstone has claimed it as such, because, he contends, Liberalism means "trust in the people," and the measure has for its object the enabling the Irish to "govern themselves." Men like Lord Hartington, Mr. Goschen, and Mr. Bright, have expressed opinions equally strong in the opposite direction, showing at least the inconclusiveness of Mr. Gladstone's definition.

I have before me a volume of political speeches, delivered by Mr. Chamberlain during the last few years, and a perusal of them affords endless illustrations of the confusing and bewildering complication which has been produced in the various attempts to modify and adapt to modern circumstances these older party-titles, without having; at the same time, a clear knowledge of the principles which they originally connoted.

"A Liberal Government," says Mr. Chamberlain, "which pretends to represent the Liberal party, must, of necessity, consist of men of different shades of opinion." Speaking of the Conservative party, he says, elsewhere: "They have stolen my ideas, and I forgive them the theft in gratitude for the stimulus they have given to the Radical programme, and for the lesson they have taught to the weak-kneed Liberals, and to those timid politicians, who strained at the [17] Radical gnat, and who now find themselves obliged to swallow the Tory camel."

"You cannot," he observes, "turn over a page of the periodical Press, without finding 'True Conservatives,' or 'Other Conservatives,' or 'an Independent Conservative,' or 'a Conservative below the gangway.'"

Speaking, under the significant title of "Tory transformation," he draws attention to the fact that Sir Michael Hicks-Beach (the then Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer), had announced his government's adhesion to a particular policy, "in terms which any Radical might approve."

In another place the same authority says:—"The old Tory party, with its historic traditions, has disappeared. It has repudiated its name, and it has become Conservative. The Conservatives, in turn, have been seeking for another designation, and sometimes they come before you as 'Constitutionalists,' and then they break out in a new place as 'Liberal Conservatives.'" Alluding to Lord Randolph Churchill, Mr. Chamberlain says: "The Whigs are left in the lurch, and the Tories have come over bodily to the Radical camp, and are carrying out the policy which we have been vainly endeavouring to promote for the last five years…. He (Lord Randolph Churchill) was a Tory-Democrat in opposition, and he is a Tory-Democrat in office."

Who shall make head or tail of this medley of terms, or who shall or could possibly say what, if any, principles are involved in their application?

Some allowance should perhaps be made for the fact that in all of the sentences quoted Mr. Chamberlain was "abusing the other side," but, even after making such an allowance, there remains a substantial residuum of truth in the charges of transformation.

During the most agitated period of the English general elections of 1885, there issued from the London Press a [18] volume entitled, "Why am I a Liberal?" which the Times considered of sufficient importance to refer to at some length in one of its leading articles. A perusal of that volume will show how numerous and various, and how conflicting even, in their fundamental principles, are the definitions, offered by prominent statesmen and politicians in the present day, of the term "Liberalism" as a word of political classification. The author of the book determined (to use the words of the Times) "to heckle as many of the Liberal chiefs as would submit to the process," and, having so far succeeded in that determination, made public the fruits of his cross-questioning. He required "fifty-six reputed Liberals" to ask themselves for a reason for the political faith that was in them, and the result is certainly instructive, if only to show how "doctors differ,"—that is to say, how little unanimity there was among so many "professed Liberals" regarding the very principles upon which their party organisation is supposed to be based.

Let us first take Mr. Gladstone's answer to this pertinent question. "The principle of Liberalism" he says, "is trust in the people, qualified by prudence…. The principle of Conservatism is mistrust of the people qualified by fear." This, it must be admitted, is absolutely unscientific as a definition of a particular political policy; and, inasmuch as it makes use of, and depends upon words of such uncertain signification as "trust" and "prudence," to both of which probably no two minds would attach exactly the same meaning, the definition itself affords no guide on the point which it professes to elucidate. Lord Beaconsfield certainly said in 1872, that "the principles of Liberty, of order, of law and of religion ought not to be entrusted to individual opinion, or to the caprice and passion of multitudes, but should be embodied in a form of permanence and power"; but this can scarcely be fairly interpreted as implying "mistrust" of the people. If, [19] moreover, we consider Mr. Gladstone's definition in the light of his late Home Rule proposals, it would seem as if he had not, during fifty years experience of practical politics, seen the application of his principle of "trust" to the Irish people, until the element of "fear" had become an extremely prominent factor among his own party.

There is a passage in the same speech of Lord Beaconsfield, from which I have already quoted, in which that statesman might well be imagined to be addressing himself to the Home Rule question as a phase of Mr. Gladstone's present-day "Liberalism." "If," says Lord Beaconsfield, "you look to the history of this country since the advent of Liberalism—forty years ago—you will find that there has been no effort so continuous, so subtle, supported by so much energy, and carried on with so much ability and acumen, as the attempts of Liberalism to effect the disintegration of the Empire of England." [4]

In any case Mr. Gladstone's definition is useless as a test by which to gauge any future legislative proposal; and we may fairly infer that Mr. Gladstone's eminently logical mind is not prepared with anything more accurate for the present.

Turn now to the definition offered by Lord Rosebery, which is even more vague, and more useless as a definition. "I am a Liberal" he says, "because I wish to be associated with the best men in the best work." If such a sentence had been composed by any politician as little known as Lord Rosebery is well known, it is very doubtful whether it would have been deemed worth putting into print, not-withstanding its brevity. The author of the book, in which the definition is published, was evidently thankful for small mercies, for he has characterised it as a "magnificent sentence."

[20]

If the "best men" all gravitate to Liberalism as Lord Rosebery understands it, there must surely be some good reason for their so doing; and that very reason involves the definition which Lord Rosebery was evidently at a loss to supply. It might fairly be deduced as a sort of corollary from such a proposition that inasmuch as Mr. Goschen has now dissociated himself from the Liberal party, he is therefore one of the "worst" of men. I shall, however, contend hereafter, that Mr. Goschen's liberalism is based upon an infinitely surer and sounder foundation than that of Lord Rosebery. Mr. Chamberlain says "Progress is the law of the world;" and "Liberalism is the expression of this law in politics." But what is progress? That is the whole question requiring solution. Mr. Chamberlain himself proposed a scheme of granting allottments to the agricultural labourer, out of estates to be compulsorily taken by the Crown at a popular valuation. Even such Liberals as Mr. Goschen and Lord Hartington, as I have said, condemned the scheme as tending towards "Socialism;" and most men of intelligence regard "Socialism" as a theory of society, the adoption of which would involve retrogression. Who then shall judge between the author of this so-called progress, and those who otherwise regard it?

Mr. Joseph Arch begins his answer thus: "Because it was by men like Richard Cobden, John Bright, and other true Liberals, that I, as a working man, am able to obtain a cheap loaf to feed my family with." What a host of anomalies such an answer suggests! Mr. Arch obviously intends, by opening his definition with such a sentence, to convey his belief that Liberalism has, before all things, produced Free Trade. But if that is correct, the whole Liberal party and the whole Liberal Press of the colony of Victoria, to which I have referred, are professing one policy and practising another; for "Liberalism" and "Free Trade," are as I have also shown, regarded by those two interests as [21] absolutely contradictory. That party and that section of the Press would brand as a renegade any fellow "Liberal" who talked of a "cheap loaf" or of "the liberty to buy in the cheapest market." And if they are right, what becomes of Mr. Arch's definition?

I prefer to regard Mr. Arch's position as the more correct; and he certainly displays a consistency of principle for, in a subsequent part of his answer, he says of the Liberals: "Their past service for the good of mankind has established my confidence in them…in the future they will confer upon the nation greater freedom by just, wise, and liberal legislation." It is obvious that "Free Trade," by its very name, as well as by its nature, has, wherever it exists, added to the freedom of citizens—yet it will be seen, these opposite and contradictory interpretations are occurring among "Liberals" themselves! One of those who were interrogated possessed a rhyming tendency, and his answer is quoted in this somewhat mystifying publication. He says:—

"I am a Liberal, because

I would have equal rights and laws,

And comforts, too, for all."

This definition, if such it may be called, is even more comprehensive than that of Mr. Chamberlain, for it practically defines Communism, under which, not only "rights and laws" should be equal, but "comforts," too! which word includes everything calculated to make mankind happy—in fact, such a definition points to a general division! But, turning to another page, we find Mr. Broadhurst taking an entirely different view. He says Liberalism "teaches selfreliance, and gives the best opportunities to the people to promote their individual interest." "Liberalism," he says, "does not seek to make all men equal; nothing," he adds, "can do that. But its object is to remove all obstacles erected by men which prevent all having equal opportunities." [22] "This, in its turn," he continues, "promotes industry, and makes the realisation of reasonably ambitious hopes possible to the poorest man among us."