Images of Liberty and Power

[Updated June 12, 2011]

Images used by the British Abolitionist

Movement in the 1780s [January 2, 2011] |

|

|

|

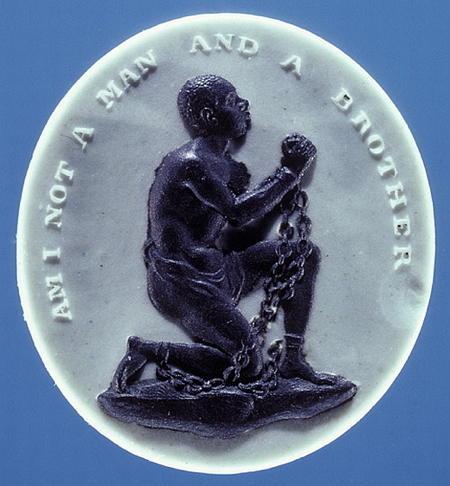

"Am I not a Man and a Brother?" Official Medallion and Motto of the British Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (1787) |

A Jasper-ware cameo of the Society's Motto,

design and production by Josiah Wedgwood (1787) |

|

|

A brass anti-slavery medal with the kneeling

African and a Christian message "whatsoever ye would that men should

do to you, do ye even so to them" (c. 1787) |

A brass seal of the Society's motto (c. 1787) |

| Observations on : The British Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade was founded in 1787 by a group (predominantly Quaker) of committed anti-slavery advocates who attempted to change public opinion about the morality of slavery and to persuade Parliament to enact its abolition throughout the empire. Early members inlcuded William Wilberforce (a member of parliament), Thomas Clarkson (a gifted orator and writer), and Josiah Wedgwood (a successful pottery industrialist). A key to their success was a clever marketing campaign to arouse public opinion in favour of abolition. Using designs created by Wedgwood, the committee disseminated medallions, cameo jewelry, seals, coins, and pamphlets showing the classic image of the kneeling African slave, with chains on his hands and legs, asking the very pertinent question which cut to the heart of the immorality of slavery: "Am I not a man and a brother?" After 20 years of campaigning the British parliament eventually passed legislation ending the slave trade in 1807. The committee then redirected its efforts to abolishing slavery itself in the colonies, which was achieved in 1833.Wedgwood's iconic image was also used in various adaptations in France and the United States in the 1830s as the aboitionist movement developed in the decades leading up to the Civil War. Versions appeared which also showed female slaves asking if they were not sisters of the free Europeans. | |

|

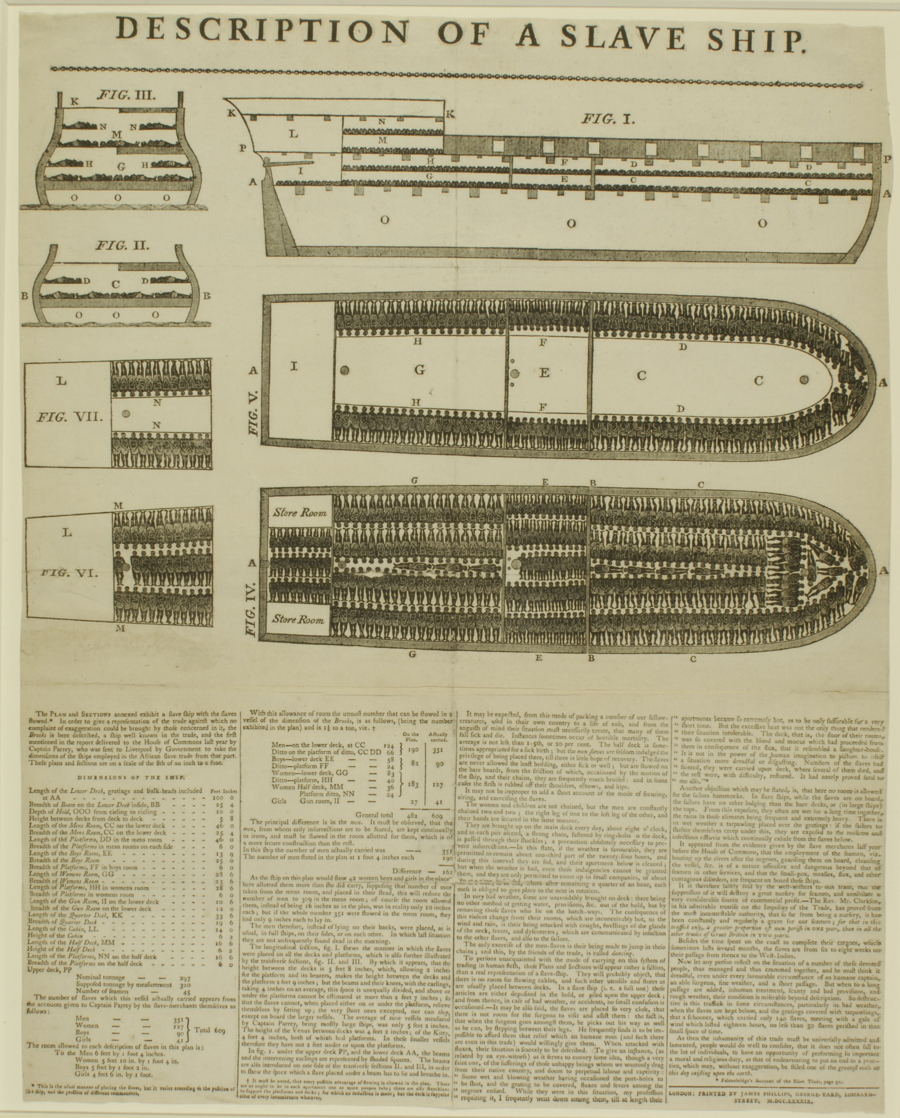

A Broadside sheet, "Description of a

Slave Ship"

(1789) |

| Observations on : Another famous image from the British

anti-slavery movement is this broadside published in London in 1789. It

was published in their thousands in various forms in Plymouth, Philadelphia,

and London as booklets and broadsides and helped spread

information about the condition of slaves in the transport ships that brought

them from Africa to the Americas. It is a clever use of cold, technical

data about a specific slave ship called the "Brooks" (note the

great detail about the size of the decks and the space available for packing

the slaves in tightly) with

a minimal use of emotive language. The data was taken from a Parliamentary

inquiry into the slave ships using British ports. One has to look closely

at the images above the text to discover that the densely packed cargo

is not bales of produce but human beings chained together. After four densely

printed columns of text it is only in the last two paragraphs that a condemnation

of the slave trade is made, the last paragraph reading:

"As then the inhumanity of this trade must be universally admitted

and lamented, people would do well to consider, that it does not often

fall to the lot of individuals, to have an opporunity of performing so

important a moral and religious duty, as that of endeavouring to put an

end to a practice, which may, without exaggeration, be stiled one of the greatest

evils at this day existing upon the earth." These images of the

Brooks and its cargo were taken up by other abolitionist groups in the

19th century, including the American and French. It also appeared in books

like Clarkson's History of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade (1808). A

full transcription of the text is provided below. [See a larger version of the image 1.8 MB JPG]. |

DESCRIPTION OF A SLAVE SHIP. [Column 1] The PLAN and SECTIONS annexed exhibit a slave ship with the slaves stowed.(*) In order to give a representation of the trade against which no complaint of exaggeration could be brought by those concerned in it, the Brooks is here described, a ship well known in the trade, and the first mentioned in the report delivered to the House of Commons last year by Captain Parrey, who was sent to Liverpool by Government to take the dimensions of the ships employed in the African slave trade from that port. The plans and sections are on a scale of the 8th of an inch to a foot. DIMENSIONS OF THE SHIP

Nominal tonnage 297 The room allowed to each description of slaves in this plan is: (*) This is the usual manner of placing the slaves, butx it varies according to the position of the ship, and the practice of different commanders. [Column 2] With this allowance of room the utmost number that can be stowed in a vessel of the dimension of the Brooks, is as follows, (being the number exhibited in the pan) and is 1 1/2 to a ton, viz. (+)

The principal difference is in the men. It must be observed that the men, from whom only insurrections are to be feared, are kept continually in irons, and must be stowed in the room allotted for them, which is of a more secure construction than the rest. In this ship the number of men actually carried was - 351 In fig. I, under the upper deck PP, and the lower deck AA, the beams and the intervening carlings are represented by shaded sqares. The beams are also introduced on one side of the transverse sections II. and III, in order to shew the space which a slave placed under a beam has to lie and breathe in. (+) It must be notd, that every possible advantage of stowing is allowed

in the plan. There are or ought to be in each apartment one of more poopoo

tubs; there are also stanchions to support the platforms and decks; for

which no deduction is made; but the deck is supported clear of every

encumbrance whatever. It may be expected, from this mode of packing a number of our fellow-creatures,

used in their own country to a life of ease, and from the anguish of

mind their situation must necessarily create, that many of them fall

sick and die. Instances sometimes occur of horrible mortality. The average

is not less than 1-5th, or 20 percent. The half deck is sometimes appropriated

for a sick birth, but the men slaves are seldom indulged the

privilege of being placed there, till there is little hope of recovery.

The slaves are never allowed the least bedding, either sick or well;

but are stowed on the bare boards, from the friction of which, occasioned

by the motion of the ship, and their chains, are frequently much bruised;

and in some cases the flesh is rubbed off their shoulders, elbows, and

hips. [Column 4] apartments became so extremely hot, as to be only sufferable for a very

short time. But the excessive heat was not the only thing that rendered

their situation intolerable. The deck, that is, the floor of their rooms,

was so covered with the blood and mucus which had proceded from them

in consequence of the flux, that it resembled a slaughter-house. It is

not in the power of the human imagination to picture to itself a situation

more dreadful or disgusting. Numbers of the slaves had fainted, they

were carried upon deck, where several of them died, and the rest were,

with difficulty, restored. It had nearly proved fatal to me also." (*) (*) Falconbridge's Account of the Slave Trade, page 31.

|