FRÉDÉRIC BASTIAT,

Introduction to Cobden and the League (1845)

April 2025 draft - with Bastiat's Notes

|

|

[Created: 23 April, 2025]

[Updated: 23 April, 2025] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

, "Introduction" to Cobden and the League, or the English Movement for the Liberty of Commerce. Translated and with Notes by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2025).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Bastiat/Books/1845-CobdenLigue/EnglishTranslation-Introduction.html

Frédéric Bastiat, "Introduction" to Cobden and the League, or the English Movement for the Liberty of Commerce. Translated and with Notes by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2025).

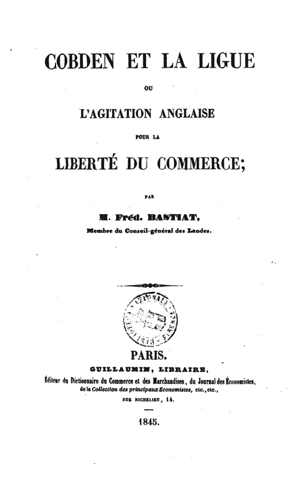

A translation of Frédéric Bastiat, Cobden et la ligue, ou l’Agitation anglaise pour la liberté du commerce (Paris: Guillaumin, 1845). “Introduction,” pp. i-xcvi.

This title is also available in a facsimile PDF of the original and various eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub.

This book is part of a collection of works by Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850).

Table of Contents

[i]

INTRODUCTION.

The person most likely to be deceived about the merit and significance of a book, after the author, is certainly the translator. Perhaps I am not exempt from this rule, for I do not hesitate to say that the book I am publishing, if it were to be read, would be a kind of revelation for my country. In matters of trade, freedom is considered here as a utopia, or something even worse. The principle may well be granted as true in the abstract; it may be conceded that it fits appropriately into a work of theory. But that is where it ends. It is not even honored with being held as true except on one condition: that it remains forever confined, along with the book that contains it, to the dust of libraries; that it exercises no influence on practice, and that it yields the domain of real affairs to its opposite principle — prohibition, restriction, protection — which is thereby admitted to be, abstractly speaking, false. If there are still a few economists who, amid the void that has formed around them, have not entirely let go of their sacred faith in the principle of freedom, they hardly dare, with an uncertain gaze, to seek its doubtful [ii] triumph in the depths of the future. Like those seeds buried under thick layers of inert earth, destined to sprout only when some cataclysm brings them back to the surface, exposing them to the life-giving rays of the sun, they see the sacred seed of liberty buried beneath the harsh shell of passions and prejudices, and they do not dare to count the number of social revolutions that must unfold before it is brought into contact with the light of truth. They do not suspect, or at least do not seem to suspect, that the bread of the strong, turned into milk for the weak, has been lavishly distributed to an entire contemporary generation; that the great principle — the right to exchange — has broken free of its shell, that it has spread like a torrent through the human mind, that it animates an entire great nation, that it has established an indomitable public opinion there, that it is about to take possession of human affairs, that it is preparing to absorb the economic legislation of a great people! That is the good news contained in this book. Will it reach your ears, friends of freedom, advocates of the unity of people, apostles of universal human fraternity, defenders of the working classes, without rekindling in your hearts confidence, zeal, and courage? Yes. If this book could penetrate beneath the cold stone that covers Tracy, Say, Comte, I believe the bones of these illustrious philanthropists would tremble with joy in their tombs.

But alas! I do not forget the restriction I myself [iii] posed: If this book is read. COBDEN! The League! THE EMANCIPATION OF TRADE! Who is Cobden? Who in France has heard of Cobden? It is true that posterity will attach his name to one of those great social reforms that, from time to time, mark humanity’s progress along the path of civilization: the restoration, not of the so-called right to work, according to the empty rhetoric of the day, but of the sacred right of working for its just and natural remuneration. It is true that Cobden is to Smith what propagation is to invention; that, assisted by his many comrades in labor, he has popularized social science; that, by dispelling from the minds of his countrymen the prejudices that sustain monopoly, this internal plunder, and conquest, this external plunder ; by thus undermining that blind antagonism which pits classes against classes and nations against nations, he has prepared a future of peace and fraternity for humanity, founded not on some utopian self-renunciation, but on the indestructible love of self-preservation and individual progress; a sentiment which some have tried to discredit under the name of self-interest rightly understood, but to which, one must acknowledge, God has entrusted the conservation and progress of the human race. It is true that this calling has taken place in our time, under our sky, at our very doorstep, and that it continues to shake to its very foundation a nation whose slightest movements usually preoccupy us to excess. And yet, who has heard of Cobden? Ah, [iv] good heavens! We have far more important things to concern ourselves with than a movement that, after all, seeks only to change the face of the world! Should we not rather be assisting M. Thiers in replacing M. Guizot, or M. Guizot in replacing M. Thiers? Are we not threatened with a new invasion of barbarians in the form of Egyptian oil or Sardinian meat? And would it not be truly regrettable if we diverted our attention, even for a moment, from such matters to something as trivial as the free communication of people, an attention that has been so usefully absorbed by the affairs of Noukahiva, Papéete, and Muscat?

The League! What League do you mean? Has England produced some Guise or Mayenne? Are the Catholics and Anglicans about to fight another Battle of Ivry? Is the unrest you talk about linked to the Irish unrest? Are there to be wars, battles, bloodshed? Perhaps then our curiosity might be piqued, for we have a profound admiration for displays of brute force! And besides, we take such an exquisite interest in religious questions, we have, after all, become such devoted Catholics, such ardent Papists of late!

The Emancipation of Trade! What a disappointment! What an anticlimax! Is the right to exchange, if it even is a right, worth our attention? Freedom of speech, of writing, of teaching? Very well! These are matters one may occasionally reflect on during idle moments, when the supreme question — the ministerial question — momentarily loosens its grip on our faculties. For, after all, these freedoms interest men of leisure. But the freedom to buy and sell! The [v] freedom to dispose of the fruits of one’s labor and to obtain, through exchange, all that it can justly yield; why, that concerns the people, the working man, the very life of the laborer! Besides, trade and exchange, how prosaic! And at best, it’s a question of well-being and justice. Well-being! Oh! too material, too materialist for an age of such noble self-denial as ours. Justice! Oh! too cold. If only it were a matter of charity, what eloquent speeches we could craft! And how delightful it is to persevere in injustice while simultaneously displaying boundless charity and philanthropy!

"The die is cast," cried Kepler; "I am writing my book; whether it is read in the present age or by posterity, what does it matter? It can wait for its reader." I am not Kepler. I have not wrested any secrets from nature. I am merely a humble and very mediocre translator. And yet, I dare to say, like the great man, this book can wait; its reader will come, sooner or later. For surely, if my country persists a little longer in the voluntary ignorance it seems to cherish regarding the immense revolution shaking all of Britain’s soil, one day it will be struck with astonishment at the sight of this volcanic fire... no, this benevolent light, shining from the North. One day — and that day is not far off — it will learn, suddenly, with no forewarning: England has opened all [vi] her ports; she has torn down every barrier that separated her from other nations; she once had fifty colonies, now she has but one, and that is the world. She trades with all who wish to trade; she buys without demanding to sell; she accepts all relations without imposing any; she invites the invasion of your products; England has freed both labor and trade. So perhaps one will want to know how, by whom, and for how long this revolution was prepared; in what impenetrable underground, in what unknown catacombs it was woven, what mysterious Freemasonry wove its threads; and this book will be here to answer: "And, my God! It happened in broad daylight, or at least in the open air (for they say there is no sun in England). It was accomplished in public, through a debate that lasted ten years, carried on simultaneously across all parts of the country. This debate increased the number of English newspapers and lengthened their format; it gave birth to thousands of tons of brochures and pamphlets; its progress was anxiously followed in the United States, in China, and even among the savage hordes of black Africans. You alone, Frenchmen, were unaware of it. And why? I could say, but is it wise to do so? No matter! Truth urges me, and I will say it. It is because among us, there are two great corrupters who bribe the press. One is called Monopoly, and the other, Party Spirit. The first said: ‘I need hatred to stand between France and foreign nations, for if [vii] nations did not hate one another, they would eventually come to understand, to unite, to love one another, and perhaps — horrible thought! — to exchange with one another the fruits of their industry.’ The second said: ‘I need national enmities, because I aspire to power, and I will reach it if I can surround myself with as much popularity as I can strip from my adversaries; if I portray them as having sold out to a foreigner ready to invade us, and if I present myself as the savior of the homeland.’ Thus, an alliance was formed between Monopoly and Party Spirit, and it was decided that all newspaper articles regarding foreign affairs would consist of two things: concealment and distortion. This is how France was systematically kept in ignorance of the fact that this book aims to reveal. But how could the newspapers succeed? Does that surprise you? It surprises me too. But their success is undeniable.

However, and precisely because I am about to introduce the reader (if I have a reader) to a world entirely foreign to him, I must be allowed to preface this translation with some general considerations on the economic regime of Great Britain, on the causes that gave birth to the League, and on the spirit and significance of this association from a social, moral, and political perspective.

It has often been said and is frequently repeated that the economic school, which entrusts the interests of various social classes to the "natural laws of economic gravitation", was born in England. From this, people have hastily concluded — with astonishing [viii] recklessness — that the terrifying contrast between opulence and poverty that characterizes Great Britain is the result of the ideas proclaimed with such authority by Adam Smith and expounded so methodically by J.-B. Say. People seem to believe that freedom reigns supremely across the Channel and presides over the unequal distribution of wealth there.

"He had witnessed," said M. Mignet a few days ago, speaking of M. Sismondi, "he had witnessed the great economic revolution of our time. He had followed and admired the brilliant effects of doctrines that had freed labor, overturned the barriers that guilds, masterships, internal customs duties, and multiple monopolies had erected against its products and exchanges; that had fostered abundant production and the free circulation of wealth, etc.

"But soon he had delved deeper, and less reassuring spectacles, less conducive to pride in human progress or confidence in human happiness, presented themselves to him in the very country where these new theories had developed most rapidly and completely, in England, where they reigned supreme. What had he seen there? All the grandeur, but also all the excesses, of unlimited production... each closed market reducing entire populations to starvation, the disorders of competition, this state of nature among interests, often more deadly than the ravages of war; he had seen man reduced to being merely a cog in a machine [ix] more intelligent than himself, crammed into unhealthy places where life expectancy did not reach half its natural duration, where family bonds were broken, and moral ideas were lost... In short, he had seen extreme poverty and a frightening degradation sadly counterbalancing and silently threatening the prosperity and splendor of a great people.

"Surprised and troubled, he wondered whether a science that sacrificed human happiness to the production of wealth... was truly a science... From that moment, he claimed that political economy should concern itself far less with the abstract production of wealth than with its just distribution."

Let us note, in passing, that political economy is no more concerned with production (let alone production in the abstract) than it is with the distribution of wealth. It is labor, it is exchange, which are the things with which it is concerned. Political economy is not an art but a science. It imposes nothing, it does not even advise, and therefore it sacrifices nothing; it simply describes how wealth is produced and distributed, just as physiology describes the workings of our organs. And it would be as unjust to blame political economy for the misfortunes of society as it would be to attribute the diseases afflicting the human body to physiology.

Be that as it may, the widely held ideas of which M. Mignet has become the all-too-eloquent interpreter naturally lead to the exercise of arbitrary power. In the face of this revolting inequality that economic theory — [x] let us be blunt — that freedom itself is supposed to have engendered, precisely where it reigns with the greatest authority, it is entirely natural that one should accuse it, reject it, denounce it, and seek refuge in artificial social arrangements, in organized labor systems, in coerced associations of capital and labor, in utopias, in short, where freedom is first sacrificed as being incompatible with the reign of equality and fraternity among men.

It is not part of our purpose here to expound the idea of free trade or to refute the many manifestations of those schools which, in our time, have usurped the name of socialism, and which have nothing in common among themselves except that very usurpation.

But it is important to establish here that, far from the economic regime of Great Britain being founded on the principle of liberty, far from wealth being distributed there in a natural manner, and far indeed from, as M. de Lamartine so aptly put it, each industry achieving through liberty a justice that no arbitrary system (of power) could grant it; there is no country in the world, except for those still afflicted by slavery, where the theory of Smith, the idea of laissez-faire, laissez-passer, is less practiced than in England, or where man has become an object which is more systematically exploited by his fellow man.

Nor should it be believed, as might be objected, that it is precisely free competition that has, over time, led to the subjugation of labor to capital and of the working class to the [xi] idle class. No, this unjust domination cannot be considered the result, nor even the abuse, of a principle that has never guided British industry. To determine its origin, one would have to go back to a time that was certainly not an era of liberty, the Norman conquest of England.

But without retracing here the history of the two races that have trod on British soil and have engaged in so many bloody struggles of a civil, political, and religious kind, it is appropriate to recall their respective positions from an economic point of view.

It is well known that the English aristocracy owns the entire surface of the country. Moreover, it holds legislative power in its hands. The only question is whether it has used this power in the interest of the community or in its own self-interest.

"If our financial code," said Mr. Cobden, addressing the aristocracy itself in Parliament, "if the statute book could reach the moon, alone and without any historical commentary, that alone would be enough for its inhabitants to learn that it is the work of an assembly of landlords."

When an aristocratic race possesses both the right to make the law and the power to enforce it, it is, unfortunately, all too true that it has made the law to its own advantage. This is a painful truth. It will grieve, I know, those benevolent souls who count on the reform of abuses not through the reaction of those who [xii] suffer them, but through the free and fraternal initiative of those who exploit them. We would very much like to be shown an example of such self-denial in history. But no such instance has ever been provided by the ruling castes of India, nor by those Spartans, Athenians, and Romans who are so often held up for our admiration, nor by the feudal lords of the Middle Ages, nor by the plantation owners of the West Indies. Indeed, it is highly doubtful that these oppressors of humanity ever considered their power to be unjust or illegitimate.

If one delves somewhat into the necessities — one might even say the fatal necessities — of aristocratic races, one soon realizes that they are significantly modified and aggravated by what has been called the principle of population.

If aristocratic classes were by nature stationary — if they did not, like all others, possess the ability to multiply — then a certain degree of happiness, and even equality, might perhaps be compatible with the regime of conquest. Once the lands were divided among the noble families, each would pass down its estates from generation to generation to its sole heir, and one could conceive that, under such an arrangement, an industrious class might peacefully rise and prosper alongside the conquering race.

But the conquerors multiply just like ordinary proletarians. While the country’s borders remain unchanged, while the number of noble estates [xiii] remains fixed, because the aristocracy, to maintain its power, takes care not to divide them and ensures they are transmitted intact from male to male, in the system of primogeniture, numerous families of the younger sons form and multiply in turn. These younger sons cannot sustain themselves through labor, since, according to noble tradition, labor is deemed disgraceful. There is, therefore, only one way to provide for them: the exploitation of the working classes. External plunder abroad is called war, conquest, and colonization. Internal plunder is called taxes, government posts, and monopolies. Civilized aristocracies generally engage in both forms of plunder; barbarian aristocracies are forced to forgo the latter for a very simple reason, there is no industrious class around them to rob. But when the resources of external plunder also run dry, what then becomes of the younger aristocratic generations among the barbarians? What becomes of them? They are smothered, for it is in the nature of aristocracies to prefer death itself to labor. [1]

"In the archipelagos of the great ocean, younger sons have no share in the inheritance of their fathers. They can only survive on the food given to them by their elders if they remain within the family, or on what the enslaved population can provide if they join the military association of the arreoys. But whichever path they choose, they cannot hope to perpetuate their race. [xiv] The inability to pass any property to their children and to maintain them in the rank in which they are born is, without a doubt, what has made it a law for them to smother their offspring ."

The English aristocracy, though influenced by the same instincts that drive the Malay aristocracy (for circumstances may vary, but human nature is the same everywhere), has found itself, if I may put it this way, in a more favorable environment. On all sides, it has had the most industrious, the most active, the most persevering, the most energetic, and at the same time the most docile population on the globe; and it has methodically exploited it.

Nothing has been more thoroughly conceived or more energetically executed than this exploitation. The possession of land places legislative power in the hands of the English oligarchy; through legislation, it systematically seizes wealth from industry. This wealth is then used to pursue abroad that policy of encroachment which has brought forty-five colonies under British rule, and these colonies, in turn, serve as a pretext for levying, at the expense of industry and for the benefit of the younger branches of the aristocracy, heavy taxes, large armies, and a powerful naval force.

Justice must be done to the English oligarchy. It has displayed marvelous skill in its dual policy of domestic and foreign plunder. Two words, which imply two prejudices, have been enough to enlist even the very classes that bear the entire [xv] burden: it has called monopoly protection and colonies markets.

Thus, the existence of the British oligarchy — or at least its legislative supremacy — is not only a scourge for England but also a constant danger for Europe.

And if this is the case, how is it possible that France pays no attention to the gigantic struggle unfolding before its eyes between the spirit of civilization and the spirit of feudalism? How is it possible that it does not even know the names of those men who deserve all the blessings of humanity — Cobden, Bright, Moore, Villiers, Thompson, Fox, Wilson, and a thousand others — who have dared to engage in the fight and who sustain it with admirable talent, courage, devotion, and energy? "It is merely a question of free trade," they say; but do they not see that commercial freedom must strip the oligarchy of both the resources it gets from internal plunder — monopolies — and the resources from external plunder — colonies? For monopolies and colonies are so incompatible with the freedom of exchange that they are nothing more than the limitation of that very freedom by arbitrary power!

But what am I saying? If France has any vague awareness of this life-or-death struggle that will decide, for a long time, the fate of human liberty, it does not seem to give its support to its triumph. In recent years, it has been made so afraid of the words liberty, competition, overproduction; it has been [xvi] told so often that these words imply poverty, pauperism, and the degradation of the working classes; it has been so repeatedly assured that there exists an English political economy that uses freedom as an instrument of Machiavellianism and oppression, and a French political economy which, under the names of philanthropy, socialism, and the organization of labor, would restore equality of conditions on earth, that it has come to detest the idea that, after all, is founded only on justice and common sense, and which can be summed up in this axiom: "That men should be free to exchange among themselves, when it suits them, the fruits of their labor." If this crusade against liberty were supported only by men of imagination who seek to formulate a science without having prepared themselves through study, the harm would not be great. But is it not painful to see true economists, driven no doubt by the passion for ephemeral popularity, yielding to these affected statements and pretending to believe what they assuredly do not, that pauperism, proletarian distress, and the suffering of the lowest social classes must be attributed to what is called excessive competition or overproduction?

Would it not, at first glance, be a most astonishing idea that poverty, destitution, and the lack of products should be caused by, what? Precisely an overabundance of products! Is it not strange to be told that if men do not have enough to eat, it is because there is too much food in the world? That if they do not have [xvii] enough to wear, it is because machines are flooding the market with too many clothes? Certainly, pauperism in England is an undeniable fact; the inequality of wealth there is striking. But why seek such a bizarre cause for these phenomena when they can be explained by a much more natural one, the systematic plunder of workers by the idle?

This is the moment to describe the economic regime of Great Britain as it stood in the years just before the partial, and in some respects deceiving, reforms that have been presented to Parliament by the current cabinet since 1842.

The first striking feature of the financial legislation of our neighbors, and one that is particularly significant for landowners on the continent, is the almost complete absence of land tax in a country burdened by such a heavy debt and such a vast administration.

In 1706 (the time of the Union under Queen Anne),...

| Land tax | £1,997,379 |

| Excise | £1,792,763 |

| Tariff | £1,549,351 |

In 1841, under the rein of Victoria:

| Land tax | £2,037,627 |

| Excise | £12,858,014 |

| Tariff | £19,185,217 |

Thus, direct taxation has remained unchanged, while consumption taxes have increased tenfold.

[**xviii**]

And it must be noted that, during this period, land rents or landowners' incomes have increased in the ratio of 1 to 7, so that the same estate which, under Queen Anne, paid 20 percent in taxes on its income now pays no more than 3 percent.

It should also be observed that land tax accounts for only one twenty-fifth of public revenue (2 million out of the 50 million that make up general receipts). In France, as in all of continental Europe, it constitutes the largest portion, especially when annual taxes are combined with the duties levied on property transfers and inheritances, duties from which landed property in Britain is exempt, even though personal and industrial property is strictly subjected to them.

The same partiality is evident in indirect taxes. Since they are uniform rather than adjusted according to the quality of the goods they are imposed on, they weigh incomparably more on the poor classes than on the wealthy classes.

Thus, Pekoe tea costs 4 shillings, and Bohea tea 9 pence; since the tax is 2 shillings, the former is taxed at 50 percent, while the latter is taxed at 300 percent.

Similarly, refined sugar, which costs 71 shillings, and raw sugar, which costs 25 shillings, are both subject to a fixed tax of 24 shillings, amounting to 34 percent for the former and 90 percent for the latter.

Likewise, common Virginia tobacco — the tobacco of the [xix] poor — is taxed at 1200 percent, while Havana tobacco is taxed at only 105 percent.

The wine of the rich is taxed at just 28 percent, while the wine of the poor is taxed at 254 percent.

And so it goes for the rest.

Next comes the corn and provisions law (the law on cereals and food), which must be properly understood.

The Corn Law, by excluding foreign wheat or subjecting it to exorbitant import duties, has the purpose of raising the price of domestic wheat, the pretext of protecting agriculture, and the effect of increasing landowners’ rents.

That the Corn Law is intended to raise the price of domestic wheat is acknowledged by all parties. Under the 1815 law, Parliament explicitly sought to maintain wheat at 80 shillings per quarter; under the 1828 law, it aimed to guarantee producers 70 shillings; and the 1842 law (which came after Sir Robert Peel’s reforms and thus does not concern us here) was designed to prevent prices from falling below 56 shillings, which is said to be the minimum for covering the cost of production. It is true that these laws have often failed to achieve their intended purpose, and even at this very moment, farmers who relied on this legislated price of 56 shillings and signed their leases accordingly are being forced to sell at 45 shillings. This is because the natural laws that tend to bring all [xx] profits to a common level have a force that despotism is not able to overcome.

On the other hand, that the so-called protection of agriculture is merely a pretext is equally evident. The number of farms available for rent is limited, whereas the number of farmers — or those who could become farmers — is not. The competition among them forces them to accept the smallest possible profits they can endure. If, as a result of high grain and livestock prices, farming became highly profitable, landlords would waste no time raising the price of leases, something they would be all the more able to do since, according to this hypothesis, a considerable number of entrepreneurs would step forward to take them up.

Finally, that the landowner (landlord) ultimately reaps all the profit from this monopoly is beyond doubt. The surplus price extracted from consumers must end up somewhere, and since it does not stay with the farmer, it must inevitably go to the landowner.

But what exactly is the burden that the wheat monopoly imposes on the English people?

To determine this, one need only compare the price of foreign wheat in bonded warehouses with the price of domestic wheat. The difference, multiplied by the number of quarters consumed annually in England, will provide the exact measure of the legal plunder exercised in this form by the British oligarchy.

Statisticians do not agree on the figures. It is likely that they are prone to some degree [xxi] of exaggeration — either upward or downward — depending on whether they belong to the party of the exploiters or the exploited. The most trustworthy authority is undoubtedly that of the officers of the Board of Trade, who were called upon to give their formal opinion before the House of Commons, called in a committee of inquiry.

Sir Robert Peel, when presenting the first part of his financial plan in 1842, said:

"I believe that full confidence is due to Her Majesty’s government and to the proposals it submits to you, especially since Parliament’s attention has been seriously drawn to these matters in the solemn inquiry of 1839."

In the same speech, the Prime Minister also stated:

"Mr. Deacon Hume, a man whose loss, I am sure, we all deeply regret, established that the country’s consumption amounts to one quarter of wheat per inhabitant."

Nothing is lacking in the authority upon which I am about to rely, neither the competence of the person giving his opinion, nor the solemnity of the circumstances in which he was called upon to express it, nor even the endorsement of the Prime Minister of England.

Here is an excerpt from this remarkable questioning on the question at hand: [2]

The President: How many years have you held positions in the Customs and the Board of Trade?

Mr. Deacon Hume: I served thirty-eight years [xxii] in the Customs and then eleven years at the Board of Trade.

Q. Do you believe that protective duties act as a direct tax on the public by raising the price of consumer goods?

A. Most definitely. I can only break down the cost of an item in the following way: one portion is its natural price; the other portion is the duty or tax, even though this duty ends up in a private individual’s pocket rather than in the public treasury.

Q. Have you ever calculated the amount of tax paid by the public due to the price increase caused by the monopoly on wheat and butcher's meat?

A. I believe we can estimate this additional burden quite accurately. It is estimated that each person consumes one quarter of wheat per year. The protectionist policy is believed to add 10 shillings to its natural price. You cannot estimate at less than double that amount the overall increase in price that it causes for meat, barley, oats, hay, butter, and cheese. This amounts to 36 million pounds sterling per year (900 million francs), and in reality, the people pay this sum out of their own pockets just as surely as if it were going to the treasury in the form of taxes.

Q. Consequently, does this make it harder for them to pay the taxes required for public revenue?

A. Without a doubt. Having already paid personal taxes, they are less able to pay national taxes.

[xxiii]

Q. Does this also result in suffering and a restriction on the industry of our country?

A. I believe that is actually the most pernicious effect. It is less easy to quantify, but if the nation enjoyed the trade that, in my view, would result from the abolition of all these protectionist measures, I believe it could easily bear an increase in taxation of 30 shillings per person.

Q. So, in your opinion, the burden of the protectionist system exceeds that of taxation?

A. I believe so, taking into account both its direct effects and its indirect consequences, which are harder to assess.

Another officer of the Board of Trade, Mr. MacGregor, responded:

"I consider that the taxes levied in this country on wealth production — due to the labor and ingenuity of its people — through restrictive and prohibitive duties far exceed, and probably more than double, the amount of taxes paid to the treasury."

Mr. Porter, another distinguished member of the Board of Trade, well known in France for his statistical work, testified in the same vein.

We can therefore take it as certain that the English aristocracy, through the operation of this single law (Corn and Provisions Law), seizes from the people a portion of the fruits of their labor, or, which amounts to the same thing, the legitimate satisfactions they could otherwise afford, amounting to 1 billion per year, and possibly [xxiv] 2 billion, if we account for the indirect effects of this law. This is, strictly speaking, the share that the aristocratic legislators, the elder sons of noble families, get for themselves.

It remained to provide for the younger sons; for, as we have seen, aristocratic races are no less capable of multiplying than others, and, under pain of dreadful internal disagreements, they must ensure a suitable fate for their younger branches, meaning one that does not involve labor, or, in other words, one that relies on plunder, since there are and can only be two ways to acquire wealth: to produce it or to seize it.

Two fertile sources of revenue were opened to the younger sons: the public treasury and the colonial system. In truth, these two alternatives are one and the same. Armies and navies are raised, in a word, taxes are levied in order to conquer colonies, and colonies are maintained to make the navy, the armies, and the taxes permanent.

As long as people believed that the exchanges taking place under an agreement of reciprocal monopoly between the metropole and its colonies were of a different and more advantageous nature than those occurring between free countries, the colonial system could be sustained by national prejudice. But when science and experience (and science is nothing but methodical experience) revealed and placed beyond doubt this simple truth, that products are exchanged for other products, [xxv] it became evident that sugar, coffee, and cotton imported from foreign countries provide no fewer commercial markets for domestic industry than these same goods which have come from the colonies. From that moment on, this regime, accompanied as it is by so much violence and so many dangers, lost any reasonable or even specious justification. It is nothing more than a pretext and an opportunity for immense injustice. Let us try to assess its impact.

As for the English people — that is, the productive class — they gain nothing from the vast expansion of colonial possessions. Indeed, if the people are wealthy enough to buy sugar, cotton, and timber for construction, what does it matter whether they obtain these things from Jamaica, India, and Canada or from Brazil, the United States, and the Baltic? English manufacturing labor must pay for the agricultural labor of the West Indies just as it would pay for the agricultural labor of the northern nations. It is therefore folly to include in economic calculations the so-called markets in the colonies which are open to England. These markets would exist even if the colonies were emancipated, simply because England buys goods from them. Moreover, England would also have access to foreign markets, which it deprives itself of by limiting its supplies to its own possessions by granting them a monopoly.

When the United States proclaimed its independence, colonial prejudices were at their height, and everyone knows that England believed its commerce would be ruined. It believed this so strongly that it ruined itself [xxvi] in advance with war expenses in an effort to keep that vast continent under its rule. But what happened? In 1776, at the start of the War of Independence, England’s exports to North America were valued at £1,300,000. By 1784, after independence had been recognized, they had risen to £3,600,000. Today, they amount to £12,400,000, a sum nearly equal to the total exports England sends to all of its forty-five colonies combined, which, in 1842, did not exceed £13,200,000. And indeed, why would exchanges of iron for cotton, or textiles for flour, cease between the two nations? Would it be because the citizens of the United States are governed by a president of their own choosing instead of by a lord-lieutenant paid at the expense of the Exchequer? But what does that circumstance have to do with commerce? And if one day we were to elect our mayors and prefects, would that prevent Bordeaux wines from being sent to Elbeuf, or Elbeuf textiles from being sent to Bordeaux?

It may be said that, since the Act of Independence, England and the United States have mutually restricted each other's products, which would not have happened if the colonial bond had not been severed. But those who make this objection surely intend to present an argument in favor of my thesis; they imply that both countries would have benefited from freely exchanging the products of their land and their [xxvii] industry. I ask: how can the exchange of wheat for iron, or tobacco for cloth, be harmful depending on whether the two nations conducting it are or are not politically independent from each other? If the two great Anglo-Saxon families are acting wisely and in accordance with their true interests by restricting their mutual trade, it must be because such exchanges are harmful. And in that case, they would have been just as justified in restricting them even if an English governor still resided in the Capitol. If, on the contrary, they have acted unwisely, then they have made a mistake — they have misunderstood their own interests — and there is no reason to believe that the colonial bond would have made them more perceptive.

Furthermore, note that the exports of 1776, which amounted to £1,300,000, could not have yielded England more than 20 percent in profit, or £260,000. Does one believe that the administration of such a vast continent did not cost ten times that sum?

Moreover, people tend to exaggerate the volume of trade that England conducts with its colonies, and especially the progress of this trade. Despite the fact that the British government compels its citizens to provide itself with goods from the colonies and the colonists to do the same from the metropole, despite the fact that customs barriers between England and other nations have, in recent years, multiplied and been greatly increased, one can see that England's foreign trade has been growing more rapidly than [xxviii] its colonial trade, as demonstrated by the following table:

| 85. | EXPORTS | 86.87. | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| to the Colonies | to foreign countries | ||

| 1831 | £10,254,940 | £26,909,432 | £37,164,372 |

| 1842 | £13,261,436 | £34,119,587 | £47,381,023 |

In both periods, colonial trade accounted for only slightly more than a quarter of total trade. The increase over eleven years amounts to about three million pounds, but it must be noted that the East Indies — where the principles of free trade were applied in the meantime — contributed £1,300,000 to this increase, while Gibraltar, which does not engage in colonial trade but rather foreign trade with Spain, accounted for £600,000. This means that the actual increase in colonial trade over an eleven-year period was only £1,100,000. During the same period, and despite our tariffs, England’s exports to France rose from £602,688 to £3,193,939.

Thus, protected trade grew by 8 percent, while hampered trade increased by 450 percent!

But while the English people did not gain — and indeed lost significantly — from the colonial system, the same cannot be said for the younger branches of the British aristocracy.

First, this system requires an army, a navy, a diplomatic corps, lords-lieutenant, governors, [xxix] residents, and agents of all kinds and titles. Although it is presented as a policy designed to promote agriculture, commerce, and industry, it is not, as far as I know, farmers, merchants, or manufacturers who are entrusted with these high positions. It can be stated with certainty that a large portion of the heavy taxes — burdens that we have seen fall mainly upon the people — are used to pay all these tools of conquest, who are none other than the younger sons of the English aristocracy.

Moreover, it is well known that these noble adventurers have acquired vast estates in the colonies. They have been granted protection, and it is important to calculate what this protection costs the working classes.

Before 1825, English legislation on sugar was highly complex.

Sugar from the West Indies paid the lowest duty; sugar from Mauritius and the East Indies was subject to a higher tax. Foreign sugar was excluded by a prohibitive duty.

On July 5, 1825, Mauritius, and on August 13, 1836, British India, were placed on equal footing with the West Indies.

The simplified legislation then recognized only two types of sugar: colonial sugar and foreign sugar. The former was subject to a duty of 24 shillings per hundredweight, while the latter was taxed at 63 shillings.

If we assume for a moment that the cost of production is the same in the colonies and abroad — for instance, [xxx] 20 shillings — it is easy to understand the effects of such legislation, both for producers and for consumers.

Foreign sugar cannot be sold on the English market for less than 83 shillings, 20 shillings to cover production costs and 63 shillings to pay the tax. If colonial production is even slightly insufficient to meet market demand, or if foreign sugar enters the market, the selling price (for there can only be one selling price) will be set at 83 shillings, and for colonial sugar, this price will be broken down as follows:

| 20 sh. | Reimbursement for cost of production |

| 24 sh. | Share for the Treasury or tax |

| 39 sh. | Amount paid for plunder or monopoly |

| 83 sh. | Price paid by the consumer |

It is clear that English law was designed to make the people pay 83 shillings for what is worth only 20, and to distribute the excess — 63 shillings — in such a way that the treasury's share would be 24 shillings, while the monopoly's share would be 39 shillings.

If things had proceeded in this way, if the law had achieved its intended purpose, then to determine the amount of plunder carried out by monopolists at the expense of the people, it would be enough to multiply 39 shillings by the number of hundredweights of sugar consumed in England.

However, as with cereals, the law failed to achieve its full effect. Limited consumption due to high prices did not turn to foreign sugar to fill the gap, and the price of 83 shillings was not reached.

Let us step out of the realm of hypotheses and consult the [xxxi] facts. Here they are, carefully drawn from official documents.

| YEAR | TOTAL CONSUMPTION | CONSUMPTION PER INHABITANT | PRICE OF COLONIAL SUGAR AT PORT | PRICE OF FOREIGN SUGAR AT PORT |

| sh. d. | sh. d. | |||

| 1837 | 3,954,810 | 16 12/13 | 34 7 | 21 3 |

| 1838 | 3,909,365 | 16 8/13 | 33 8 | 21 3 |

| 1839 | 3,825,599 | 15 12/13 | 39 2 | 22 2 |

| 1840 | 3,594,834 | 14 7/9 | 49 1 | 21 6 |

| 1841 | 4,058,435 | 16 1/2 | 39 8 | 20 6 |

| average | 3,868,668 | 16 1/6 | 39 5 | 21 5 |

From this table, it is very easy to deduce the enormous losses that the monopoly has inflicted, both on the Exchequer and on English consumers.

Let us calculate in French currency and round numbers for the reader’s easier understanding.

At a rate of 49 francs 20 centimes (39 shillings 5 pence), plus 30 francs in duties (24 shillings), it has cost the English people a total of 306.5 million francs to consume 3,868,000 hundredweights of sugar annually, broken down as follows:

- 103.5 million francs, which would have been the cost of the same quantity of foreign sugar at 29 francs 75 centimes (21 shillings 5 pence).

- 116 million francs in taxes for revenue at 30 francs (24 shillings).

- 86.5 million francs, the share of the monopoly resulting from the difference between the colonial price and the foreign price.

- Total: 306 million francs.

[xxxii]

It is clear that, under a regime of equality and with a uniform tax of 30 francs per hundredweight, if the English people had wanted to spend 306 million francs on this type of consumption, they would have received, at a price of 26 francs 75 centimes plus a 30-franc tax, 5,400,000 hundredweights of sugar, or 22 kilograms per person instead of 16.

According to this hypothesis, the Treasury would have collected 162 million francs instead of 116 million.

If the people had chosen to maintain their current level of consumption, they would have saved 86 million francs annually, which could have been used to obtain other satisfactions and open new markets for their industry.

Similar calculations, which we spare the reader, prove that the monopoly granted to Canadian timber owners costs the working classes of Great Britain an excess of 30 million francs, independently of the revenue tax.

The coffee monopoly imposes an additional 6,500,000 francs burden on them.

Thus, from just three colonial commodities alone, a total of 124 million francs is taken directly from consumers’ pockets — over and above the natural price of these goods and the revenue taxes — and transferred, without any compensation, into the hands of the colonists.

I will conclude this already too lengthy discussion with a quotation from Mr. Porter, a member of the Board of Trade:

"In 1840, without even considering import duties, we paid 5 million pounds more than [xxxiii] any other nation would have paid for the same quantity of sugar. In the same year, we exported goods worth £4,000,000 to the sugar colonies. This means that we would have gained a million by following the true principle — which is to buy from the most advantageous market — even if we had simply given the planters all the goods they took from us for free."

M. Charles Comte had already foreseen, as early as 1827, what Mr. Porter has now confirmed in figures:

"If the English were to calculate how much merchandise they must sell to the slaveholders in order to recover the expenses they incur to secure their business, they would realize that their best course of action would be to give them their goods for free and, at that price, purchase commercial freedom."

We are now, it seems to me, in a position to assess the degree of freedom that labor and trade enjoy in England and to judge whether this is truly the country in which one should study the disastrous effects of free competition on the just distribution of wealth and the equality of conditions.

Let us summarize and condense the facts we have established:

- The eldest branches of the English aristocracy own the entire surface of the land.

- The land tax has remained unchanged for 150 years, even though land rents have [xxxiv] increased sevenfold. It accounts for only one twenty-fifth of public revenue.

- Real estate property is exempt from inheritance taxes, while personal property remains subject to them.

- Indirect taxes weigh far less on high-quality goods used by the wealthy than on lower-quality goods consumed by the people.

- Through the Corn Law, these same eldest branches of the aristocracy impose a tax on the people's food supply, which the best authorities estimate at one billion francs.

- The colonial system, when pursued on a very large scale, requires heavy taxation. These taxes, almost entirely paid by the working classes, also almost entirely constitute the patrimony of the younger branches of the idle class.

- Local taxes, such as tithes, also reach these younger branches through the established Church.

- If the colonial system requires a large growth in the size of military force, maintaining this force, in turn, depends on the colonial regime, and this regime brings with it monopolies. We have seen that, from just three products alone, these monopolies cause the English people a direct loss of 124 million francs.

I felt it necessary to give some breadth to the presentation of these facts because they seem to me capable of [xxxv] dispelling many errors, many prejudices, and many blind misconceptions. How many solutions, both obvious and unexpected, do they not offer to economists and politicians alike?

First, how can those modern schools of thought that seem to have taken it upon themselves to drag France into this system of mutual plunder — by making it fear competition — how, I ask, can these schools persist in claiming that freedom is what has caused pauperism in England? Say instead that it has arisen from organized, systematic, persistent, and ruthless plunder. Is this explanation not simpler, truer, and more satisfactory? What do you say! Freedom would lead to pauperism? Free competition, free transactions, and the right to exchange property that one has the right to destroy, would these imply an unjust distribution of wealth? Then providential law itself must be wicked indeed! And should we then hasten to replace it with human law? And what kind of law? A law of restriction and prevention! Instead of "laisser faire" (letting things be), we should prevent them from happening; Instead of "laissez passer" (letting goods circulate), we should prevent their circulation; Instead of "laisser échanger" (allowing exchanges), we should prevent exchanges; Instead of letting workers get paid for the work which they have done, we should give that money to those who have not worked! Is this truly the only way to prevent inequality of wealth among men? "Yes," you say, "experience has shown us: freedom and pauperism coexist in England." But you can no longer say this. [xxxvi] Far from freedom and poverty being linked in a cause-and-effect relationship, one of them — freedom — does not even exist in England. Workers may be free to work, but they are not free to enjoy the fruits of their labor. What coexists in England is not liberty and poverty, but a small number of plunderers and a large number of the plundered, and one does not need to be a great economist to conclude that the opulence of the former is the cause of the poverty of the latter.

Moreover, if we accept the overall situation of Great Britain as we have just described it, and if we recognize the feudal spirit that dominates its economic institutions, we must be convinced that the financial and customs reform now taking place in this country is not only an English question, it is a European and humanitarian issue as well. This is not merely a matter of a change in the distribution of wealth within the United Kingdom; it is about a deep transformation in the actions which it takes abroad. With the fall of the British aristocracy’s unjust privileges, so too will fall the policies for which England has been so often criticized, along with its colonial system, its usurpations, its armies, its navy, and its diplomacy, insofar as they have been oppressive and dangerous to humanity.

This is the glorious triumph that the League aspires to when it demands: [3]

"The total, immediate, and unconditional abolition of all monopolies and all protective duties in favor of agriculture, manufacturing, commerce, and [xxxvii] navigation, in short, the absolute freedom of trade."

I will say little here about this powerful association. The spirit that drives it, its beginnings, progress, struggles, setbacks, victories, ambitions, and means of action, all of this will manifest itself, full of life and movement, in the course of this work. I do not need to meticulously describe this great body, for I am bringing it to life, breathing and acting, before the French public, from whose eyes, by an incomprehensible feat of manipulation, the press subsidized by monopoly has kept it hidden for so long.

In the midst of the distress that the regime we have described inevitably imposed upon the working classes, seven men gathered in Manchester in October 1838. And with the resolute determination that characterizes the Anglo-Saxon race, they resolved to overthrow all monopolies through legal means, to accomplish, without disorder, without bloodshed, and by the sole force of public opinion, a revolution as profound, perhaps even more profound, than the one our fathers carried out in 1789.

Certainly, it required extraordinary courage to embark on such an undertaking. The opponents they had to confront possessed wealth, influence, the legislature, the Church, the State, the public treasury, the land, government positions, and monopolies. Moreover, they [xxxviii] were surrounded by traditional respect and veneration.

And where could they find a foothold against such an imposing array of forces? Among the industrious classes? Alas! In England, as in France, each industry believes its existence is tied to some shred of monopoly. Protectionism has gradually extended to everything. How could one convince people to prefer distant and seemingly uncertain interests over immediate and tangible ones? How could one dispel so many prejudices, so many sophisms, so deeply embedded in people's minds by time and self-interest? And even if public opinion could be enlightened in all ranks and classes — a formidable task in itself — how could it be given enough energy, perseverance, and coordinated action to take control of the legislature through elections?

The magnitude of these challenges did not deter the founders of the League. After facing and assessing them, they believed they had the strength to overcome them. The Movement was launched.

Manchester became the cradle of this great movement. It was natural for it to arise in northern England, among the manufacturing population, just as it is natural that one day, a similar movement will emerge among the agricultural population of southern France. Indeed, in both countries, the industries that provide the means for trade are the ones that suffer most immediately from its prohibition. It is clear that if trade were free, the English would send us [xxxix] iron, coal, machines, textiles — in short, the products of their mines and factories — which we would pay for with grain, silk, wine, oil, and fruits, that is, with the products of our agriculture.

This explains, at least to some extent, the seemingly odd name chosen by the association: Anti-Corn Law League [4] . This narrow designation undoubtedly contributed to diverting Europe’s attention from the full scope of the Movement. We therefore find it essential to explain the reasons behind its adoption.

The French press has rarely spoken of the League (we will explain why elsewhere), and when it could not avoid doing so, it at least made sure to rely on its title — Anti-Corn Law — to suggest that it was merely a specific issue, a simple reform of the law regulating grain imports in England.

But this is not the sole purpose of the League. It aspires to the complete and radical destruction of all privileges and monopolies, to absolute freedom of trade, to unlimited competition, which implies the downfall of aristocratic supremacy in all its injustices, the dissolution of colonial ties insofar as they are exclusive, and a complete revolution in Great Britain’s domestic and foreign policy.

To cite just one example: today, we see the free traders siding with the [xl] United States on the question of Oregon and Texas.What do they care, after all, whether these territories govern themselves under the Union’s jurisdiction rather than being ruled by a Mexican president or an English lord commissioner, so long as everyone is free to sell, buy, acquire property, and work there; so long as every honest transaction is free? Under these conditions, they would gladly cede both Canada and Nova Scotia, and the West Indies to the United States as a bonus; they would even give them up without this condition, firmly convinced that free trade will, sooner or later, become the guiding principle of international transactions [5] .

[xli]

But it is easy to understand why the free-traders began by concentrating all their efforts against a single monopoly, the grain monopoly: it is the keystone of the entire system. It represents the aristocracy’s share, the special privilege that the legislators granted themselves. If this monopoly is taken away from them, they will easily concede all the others.

Moreover, it is the burden that weighs most heavily on the people and the one whose injustice is easiest to demonstrate. A tax on bread! On food! On life itself! This, certainly, is a rallying cry uniquely suited to awaken the sympathy of the masses.

It is undoubtedly a great and noble spectacle to see a small group of men attempting, through hard work, perseverance, and determination, to destroy the most oppressive and most powerfully organized regime — second only to slavery — that has ever weighed upon a great people and upon humanity. And they do so without resorting to brute force, without even seeking to stir up [xlii] public outrage. Instead, they illuminate with a bright light every fold and crease of this system, they refute every sophismon which it rests, and they instill in the masses the knowledge and virtues that alone can free them from the yoke that crushes them.

But this spectacle becomes even more imposing when we see the battlefield expanding every day as new questions and interests enter the struggle one after another.

At first, the aristocracy scorns to enter the arena. It believes that since it holds political power through land ownership, material power through the army and navy, moral power through the Church, legislative power through Parliament, and, finally, the power of public opinion itself, through that false national grandeur that flatters the people and seems tied to the very institutions now under attack.When the aristocracy considers the height, strength, and cohesion of the fortifications in which it has entrenched itself; when it compares its forces to those of a handful of isolated men opposing it; it believes it can remain silent and indifferent.

However, the League makes progress. If the aristocracy has the established Church on its side, the League calls upon all the dissenting churches for support. These churches, unlike the established one, are not tied to the monopoly through tithes; they sustain themselves through voluntary contributions, meaning they depend on public confidence. They soon realized that the [xliii] exploitation of man by man, whether called slavery or protectionism, is contrary to Christian doctrine. Sixteen hundred dissenting ministers responded to the League’s call. Seven hundred of them, coming from all parts of the kingdom, gathered in Manchester. They deliberated, and the result of their discussion is that they will go out and preach throughout England that free trade is in accordance with providential laws, which is their mission to proclaim.

If the aristocracy has property in land and the agricultural class on its side, the League relies on the property in one's labor,in one's faculties, and in one's mind. Nothing equals the zeal with which the manufacturing classes eagerly contribute to this great cause. Spontaneous subscriptions bring 200,000 francs to the League’s funds in 1841, 600,000 francs in 1842, 1 million francs in 1843, 2 million francs in 1844. And in 1845, a sum twice, perhaps three times as large will be devoted to one of the League’s key objectives: registering a great number of free-traders on the electoral lists. Among the facts related to these subscriptions, one in particular made a profound impression on the public: on November 14, 1844, a subscription list was opened in Manchester. By the end of that same day, it had raised £16,000 (400,000 francs). Thanks to these abundant resources, the League, presenting its ideas in varied and accessible forms, distributes them among the people through brochures, pamphlets, posters, and countless newspapers. [xliv] The League divides England into twelve districts, each of which has a professor of political economy. Moreover, the League itself, like a traveling university, holds public meetings in every city and county of Great Britain. It seems, indeed, that he who directs human affairshas provided the League with unexpected means of success: The postal reform allows it to maintain a correspondence with the electoral committees it has established throughout the country, with over 300,000 letters sent annually. The railways give its movements a sense of ubiquity, so that the same men who agitate in Liverpool in the morning are stirring up Edinburgh or Glasgow in the evening. Electoral reform has opened the doors of Parliament to the middle class,allowing the founders of the League — Cobden, Bright, Gibson, Villiers — to confront the monopolists directly, within the very chamber where these monopolies were once enshrined into law. They enter the House of Commons, and there they form — not a Whig party, nor a Tory party, but something unprecedented in constitutional history — a party that refuses to sacrifice absolute truth, absolute justice, and absolute principles for the sake of personal ambition, political maneuvering, or the strategies of ministers and members of the the opposition.

But it was not enough to rally the social classes directly burdened by the monopoly; it was also necessary to open the eyesof those who sincerely believed [xlv] that their well-being, and even their very existence, depended on the protectionist system. Mr. Cobden undertook this difficult and perilous task. In the space of two months, he organized forty meetings in the very heart of the agricultural population. There, often surrounded by thousands of laborers and farmers — among whom, as one might expect, agents of disorder had been sent by the interests which were under threat — he displayed a courage, composure, skill, and eloquence that astonished, if not won over, even his most ardent adversaries. Placed in a situation comparable to that of a Frenchman preaching free trade in the ironworks of Decazeville or among the miners of Anzin, one hardly knows what to admire most in this remarkable man — at once economist, orator, statesman, strategist, and theorist — to whom one might justly apply what was once said of Destutt de Tracy: "By the sheer force of common sense, he attains genius."His efforts earned the reward they deserved, and the aristocracy had the distressing realization that the principle of free trade was rapidly gaining ground among the population which is tied to agriculture.

Thus, the time when it could cloak itself in scornful arrogance is over; the aristocracy has finally emerged from its passivity. It tries to take the offensive, and its first move is to slander the League and its founders. It scrutinizes their public and private lives, but soon, forced to abandon this battlefield of personal attacks, where it might well suffer more casualties and wounds [xlvi] than the League, it summons to its aid the army of sophisms that, in all times and in all countries, have served as the pillars of monopoly. Protection for agriculture, Invasion of foreign products, Falling wages due to cheap food, National independence, Draining of precious metals, Guaranteed colonial markets, Political supremacy, Naval dominance. These are now the questions being debated, not just among scholars, not just from one academic school to another, but directly before the people, in a struggle between democracy and aristocracy.

However, it turns out that the League members are not merely courageous agitators; they are also deeply knowledgeable economists. Not one of these many sophisms withstands the challenge of discussion, and when necessary, parliamentary inquiries, provoked by the League, expose their emptiness.

The aristocracy then adopts a new approach. Poverty is immense, profound, horrible, and its cause is obvious: an unbearable inequality governs the distribution of social wealth. But against the League’s banner, which bears the word “justice,” the aristocracy raises a different banner, bearing the word “charity”. It no longer denies the suffering of the people, but it hopes to create a powerful distraction, through almsgiving.

"You suffer," it tells the people, "because you have multiplied too much. I will prepare a vast system of emigration for you." (Motion by Mr. Butler.) "You are dying of hunger. I will grant each family a small garden and a cow." (Allotments.) "You are exhausted from overwork. That is because too much is demanded of you. I will limit [xlvii] the length of your working hours." (The Ten Hours Bill.)

Then come charitable subscriptions to provide the poor with free public baths, recreation areas, the benefits of national education, and so on. Always almsgiving, always palliatives. But as for the cause that makes them necessary, as for the monopoly, as for the artificial and unjust distribution of wealth, they do not speak of touching it.

Here, the League must defend itself against a particularly insidious attack. The aristocracy, by embracing charity, seems to claim a monopoly on philanthropy. Meanwhile, it seeks to trap the League within the rigid confines of exact, cold justice which, unlike charity (even when impotent or hypocritical), is far less effective in eliciting the impulsive gratitude of those who suffer.

I will not repeat the objections that the League has raised against all these so-called charitable institutions; some of them will be seen throughout this work. It is enough to say that the League has supported those efforts that undeniably serve the public good. For instance, among the free-traders of Manchester, nearly one million francs was collected to provide more space, air, and light to the working-class neighborhoods. An equal sum, also raised through voluntary subscriptions, was dedicated to establishing schools in the city. At the same time, however, the League never ceased to expose the hidden trap beneath this grand display of philanthropy:

"When the English are [xlviii] starving," it said, "it is not enough to tell them: ‘We will send you to America, where food is abundant.’ One must first allow that food to enter England. It is not enough to give working-class families a garden to grow potatoes; above all, one must not deprive them of the earnings they could obtain from more substantial nourishment. It is not enough to limit the excessive labor imposed on them by spoliation; one must abolish spoliation itself, so that ten hours of work will be worth twelve. It is not enough to give them air and water; they must be given bread, or at the very least, the right to buy bread. It is not philanthropy but freedom that must be opposed to oppression; it is not charity but justice that can cure the wounds of injustice. Almsgiving can only ever be insufficient, fleeting, uncertain, and often degrading.

At the end of all its sophisms, its evasions, and its delaying tactics, the aristocracy still had one last resort: its parliamentary majority, the majority that relieves it of the need to be right. Thus, the final act of the Movement had to take place within the electoral colleges. After having popularized sound economic principles, the League now had to channel the practical efforts of its countless supporters. Its mission: to profoundly change the electoral constituencies of the kingdom; to undermine aristocratic influence; to bring the full weight of the law and public opinion against political corruption. This marks the new phase into which [xlix] the Movement has entered, with an energy that only seems to grow with progress. Vires acquirit eundo (It gains strength as it moves forward). At the call of Cobden, Bright, and their allies, thousands of free-traders are registering as voters, while thousands of monopolists are being removed from the electoral lists. The speed of this movement makes it possible to foresee the day when Parliament will no longer represent a single privileged class, but the entire community.

One may ask whether so much effort, so much zeal, and so much dedication have had no influence on public affairs so far, whether the progress of liberal ideas in the country has had any reflection in legislation.

At the beginning of this work, I described the economic regime of England before the commercial crisis that gave birth to the League; I even attempted to calculate the amount of the extortion that the ruling classes imposed on the subjugated classes through the dual mechanism of taxation and monopolies.

Since then, both taxation and monopolies have undergone changes. Who has not heard of the financial plan that Sir Robert Peel has just submitted to the House of Commons, a plan that is merely a continuation of reforms initiated in 1842 and 1844, and whose full implementation is reserved for future sessions of Parliament? I sincerely believe that, in France, the true spirit of these reforms has been misunderstood, alternately exaggerated or underestimated. I hope to be excused, then, if I go into some details here, [l] though I will strive to be as brief as possible.

Plunder (forgive me for frequently repeating this term, but it is necessary to dispel the gross misconception implied by its synonym, protection) ; plunder, when elevated to a system of government, had produced all its natural consequences: extreme inequality of wealth, poverty, crime and disorder among the lower classes, a massive decline in overall consumption, a weakening of public revenues, and a growing deficit that, year after year, threatened to undermine the credit of Great Britain. Clearly, it was impossible to remain in a situation that threatened to sink the ship of state. The Irish unrest, commercial unrest, the incendiary riots in the agricultural districts, the Rebecca riots in Wales, the Chartist movement in industrial cities; these were all merely different symptoms of the same underlying phenomenon: the suffering of the people. But the suffering of the people — that is, the suffering of the masses, which means the vast majority of humanity — will eventually affect every class in society. When the people have nothing, they buy nothing. When they buy nothing, factories shut down. When factories shut down, farmers cannot sell their harvests. When farmers cannot sell, they cannot pay their rents. Thus, even the great landowning legislators found themselves trapped by the very laws they had enacted; they were caught between the bankruptcy of their tenant farmers and the bankruptcy of the state [**li**] and were threatened both in their landholdings and their financial assets. The aristocracy could feel the ground trembling beneath its feet. One of its most distinguished members, Sir James Graham (now Home Secretary), had even written a book warning his colleagues of the dangers surrounding them:

“If you do not yield part, you will lose everything. A revolutionary storm will sweep away from the country, not just your monopolies, but also your honors, your privileges, your influence, and your ill-gotten wealth.”

The first expedient to counter the most immediate threat — the deficit — was, in the well-worn phrase of statesmen, to "demand from taxation all that it can yield." But it so happened that the very taxes they tried to increase were the ones that had already drained the Treasury dry. They were forced to abandon this solution for the foreseeable future, and the first act of the new government, upon assuming power, was to declare that taxation had reached its absolute limit: "I am bound to say that the people of this country have been brought to the utmost limit of taxation." — Peel, speech of May 10, 1842

Anyone who understands the respective positions of the two great classes whose interests and struggles I have described, can easily see what problem each side needed to solve.

For the free-traders, the solution was simple: abolish all monopolies; free imports, which would necessarily increase trade and, consequently, [lii] boost exports; provide both bread and employment for the people; stimulate consumption, thereby increasing indirect tax revenues; and ultimately, restore balance to the state's finances.

For the monopolists, the problem was virtually insoluble: How to alleviate the suffering of the people without giving up monopolies? How to increase public revenue without raising taxes? How to maintain the colonial system without reducing national expenditures?

The Whig government (Russell, Morpeth, Melbourne, Baring, etc.) presented a compromise plan, weakening monopolies and the colonial system without destroying them. It was not accepted either by the monopolists or by the free-traders; the former demanded absolute monopoly, the latter demanded unlimited freedom. The monopolists cried: "No concessions!" The free-traders cried: "No compromises!"

Defeated in Parliament, the Whigs appealed to the electorate, which decisively sided with the Tories, that is, with protectionism and the colonies. The Peel ministry was formed (1841) with the explicit mission of finding the impossible solution I described earlier to the great and terrible problem posed by the deficit and widespread poverty. And it must be admitted that Peel handled this challenge with remarkable foresight and determination.

I will now attempt to explain Sir Robert Peel’s financial plan, at least as I understand it.

[liii]

One must keep in mind the various objectives that this statesman, Sir Robert Peel, had to pursue, considering the party that supported him. They are the following:

- Restore balance to the state's finances.

- Relieve the burden on consumers.

- Revive commerce and industry.

- Preserve, as much as possible, the monopoly which by its very nature was aristocratic, namely the Corn Laws.

- Maintain the colonial system, along with the army, the navy, and high-ranking positions for the younger branches of the aristocracy.

- It is also likely that this remarkable man, who more than anyone else knows how to read the signs of the times and sees the League’s principles spreading rapidly across England, harbored a personal but noble ambition: to secure the support of the free-traders when they won the majority, so that he himself could seal the triumph of free trade, ensuring that no other official name but his own would be attached to the greatest revolution of modern times.

There is not a single measure or speech by Sir Robert Peel that does not align perfectly with the short- or long-term objectives of this program. This will soon become evident.

The pivot around which all the financial and economic reforms we are about to discuss revolve is the income tax.

The income tax, as is well known, is a levy on all forms of income. [liv] This tax is by its nature temporary and patriotic; it has only been imposed in the most serious circumstances, and until now, only in times of war. Sir Robert Peel obtained Parliament’s approval for it in 1842, for a period of three years; it has now been extended until 1849. For the first time in history, instead of being used for the purpose of destruction and to inflict the evils of war on humanity, these useful reforms became the tool which nations could use if they wanted to enjoy the benefits of peace.

It is worth noting that all incomes below £150 sterling (3,700 francs) are exempt, meaning that only the wealthy are taxed. Much has been said — on both sides of the Channel — that the income tax has now been permanently established in England’s financial system. But anyone who understands the nature of this tax and the way it is collected knows that it cannot become a permanent fixture, at least in its current form. If the government harbors any long-term plans regarding this tax, it is likely aiming to accustom the wealthy classes to contributing a larger share to public expenses, perhaps preparing the ground for a land tax that would be more in harmony with the needs of the state and the demands of a equitable form of distributive justice.

Regardless, the first goal of the Tory government — the restoration of balance in the state's finances — was achieved thanks to the resources provided by [lv]the income tax. The deficit, which had threatened England’s credit, at least temporarily disappeared.

By 1842, a surplus in revenue was already anticipated. The question was how to apply it to the second and third objectives of the program: relieving the burden on consumers, reviving commerce and industry.

This led to a long series of trade reforms implemented in 1842, 1843, 1844, and 1845. We do not intend to detail each of these reforms but will instead focus on the principles which lie behind them.