CHARLES DUNOYER,

"On the Public Spirit in France, and particularly on the spirit of public officials" (Part 1) (July 1814)

Charles Dunoyer (1786-1862) |

|

[Created: 11 May, 2025]

[Updated: 11 May, 2025] |

Source

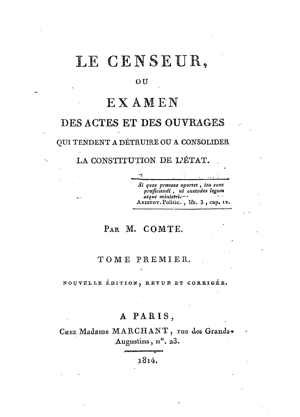

, "On the Public Spirit in France, and particularly on the spirit of public officials", Le Censeur. T. 1, No. 4. (33(sic)-28 July 1814), pp. 156-72.http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Comte/CenseurAnthology/EnglishTranslation/C1-02-Dunoyer_PublicSpirit1_T1_1814.html

"O" (Charles Dunoyer), "On the Public Spirit in France, and particularly on the spirit of public officials", Le Censeur. T. 1, No. 4. (33(sic)-28 July 1814), pp. 156-72.

A translation of "O" (Charles Dunoyer), ”De L’esprit public en France, et particulièrement de l’esprit des fonctionnaires publics.” Le Censeur, T. 1, No. 4. (33(sic)-28 July 1814), pp. 156-72.

This is part of an Anthology (in French originally) of writings by Charles Comte (1782-1837), Charles Dunoyer (1786-1862), and others from their journal Le Censeur (1814-15) [ToC] and Le Censeur européen (1817-1819) [ToC].

See also other works by Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer.

[156]

On the Public Spirit in France, and particularly on the Spirit of Public Officials.

Nothing is more different, one might even say more opposed, than the social spirit of modern people and that of the people of antiquity. [1] The most striking and profound trait of the character of ancient people is their patriotism. This sentiment, which serves as the foundation of their morality, blends with all their personal affections [157] and in some sense identifies them with the political bodies to which they belong. Love of country, by contrast, forms only a barely perceptible feature in the moral physiognomy of modern people. They are connected to the State only remotely, by an extremely weak thread; all the activity of their soul is exercised within the narrow circle of their individual affections and is exhausted upon petty personal interests. The citizens of the ancient republics were particularly bound together by their shared attachment to the homeland; those of modern states are connected to public affairs only through the private sentiments that unite them with one another, and in exact proportion to the strength of those sentiments. A citizen in the ancient world referred everything to the State; a citizen in the modern world brings everything back to himself or to the small number of individuals with whom he shares affections or interests. The ancients possessed public spirit; the moderns have rarely risen above the spirit of caste, sect, or clique, and for a long time now egoism has isolated the great majority of men.

This essential difference between the morals of ancient and modern times had to be an inevitable consequence of the difference in the political institutions of the two eras. Not only had the legislators of antiquity recognized the sovereignty of the people, but they had even left them the direct exercise of sovereign power; and as this exercise had become their most habitual occupation [158] and their keenest pleasure, one easily understands how they came to regard public affairs as their most personal affair, and the interest of the State as their most immediate interest.

In our modern times, by contrast, not only have very few people exercised sovereignty, either directly or by delegation, but their governments have almost always denied that sovereignty resided in them; they have made the most sustained and best-coordinated efforts to prevent them from seizing supreme power or sharing in its exercise. They have called them their subjects, and often treated them as slaves. From that point on, the people of modern states, having no public existence and being connected to their governments by no immediate interest, were bound to withdraw back upon themselves and concern themselves only with their domestic and private lives.

On the other hand, whereas the institutions of the ancient states formed a coherent system, all parts of which, conceived in the same spirit, acted upon men in a uniform manner and led them to a common goal, those of our modern governments, crafted at different times and often with contrary intentions, push them in a thousand opposing directions, producing only diverse interests and sentiments. Finally, while among the celebrated people of antiquity all institutions aimed to form citizens, [159] the sole common objective of those in modern states has almost always been to prevent men from becoming such. With this in view, governments have proscribed everything that might enlighten men as to their political rights; they have favored the prejudices most apt to keep them in ignorance or error on this point; they have granted special support to vain sciences and frivolous arts, to everything that can distort the mind or soften the heart; and they have succeeded in producing clever and corrupt men, who know everything except how to conduct themselves; civilized men who can be bound with ribbons; compliant and polished men who sacrifice the interests of the State to their most trifling self-interest without the slightest remorse; charming men, in short, who seem animated by a spirit of universal benevolence, and whose narrow and arid souls form no great or generous thought.

The French people are said to be the most civilized, the most polished, and the least capable of patriotism among all people. Even if that were true, it would be scarcely surprising, considering the particular circumstances in which they have found themselves and the efforts that have been made, over fourteen centuries, to enslave and corrupt them. Their history demonstrates clearly that public spirit could never take root among them at any time, and that their government, their laws, their religion, their prejudices, and their customs have consistently opposed its development and its progress.

[160]

The Franks formed a national body before their establishment in Gaul. Upon settling among the Gauls, the bond that had united them until then began to loosen and soon broke entirely. For a time they did not mix with the conquered; but while several causes kept them separate, other causes drew them closer together. As a result, without yet forming a single body with the people of Gaul, they were nonetheless less tightly united among themselves. The immediate effect of the conquest, then, was to weaken their national spirit. Soon, new factors further contributed to this weakening; the Franks, instead of remaining together in a single region, spread out and settled here and there in various provinces; as they thus mixed with the Gauls, their national character faded, their patriotism grew tepid, they no longer felt the common interest that bound them, and they eventually ceased to form a distinct national body.

However, they could not form one with a people who had been shaped by long domination under the yoke of slavery, and who for nearly five centuries had thought and acted only as it pleased the emperors of Rome. Thus, by blending in with the Gauls, they lost their character without acquiring a new one. Love of ease and riches subdued their once independent spirits; they took on all the weaknesses of the conquered people and became as suited to servitude as they. Their chiefs took advantage of these tendencies to [161] seize the sovereign authority they alone had exercised until then; from that moment the government became nothing but a tyranny, the nation was divided into two classes: the rulers and the ruled; [2] and since their interests were no longer shared, any national spirit became in a sense impossible.

Soon, contrary interests multiplied within the State and made the birth of a public spirit ever more difficult. The great lords, whom the kings had showered with wealth because they had needed their help to subjugate the people, believed themselves powerful enough to resist the kings and to free themselves from their authority. The priests, who had contributed no less than the great lords to establishing the kings’ dominion on earth by attributing their power to heaven, and who had received immense rewards for this service; the priests, who had engaged in such a lucrative trade in divine justice with them, thought themselves able to follow the example of the great lords and proclaimed their own independence. From that moment, kings, nobles, and priests waged furious wars against one another; and amid their bloody disagreements a new kind of domination formed, which soon produced new disorders. The leudes (a land owner who owed services to a lord), the bishops, and the abbots introduced seigneuries (feudal domains) on their lands; these seigneuries multiplied and became so many subordinate tyrannies, tyrannies all the more severe as [162] their action was more immediate and the oppressed was placed closer to the oppressor. [3] France was then divided into as many enemy states as there were individual seigneuries; and within each of these small despotic states, there still existed two opposing interests: that of the masters and that of the slaves. Finally, a way was found to perpetuate the divisions and to embed anarchy within the heart of France. The privileges granted to or usurped by individuals were made hereditary within families. Benefices and seigneuries became hereditary; as a result, the children of a leude were considered leudes, the children of a seigneury (feudal lord) were considered seigneuries (feudal lords); certain individuals thus found themselves endowed from birth with a certain preeminence, and their families, called nobles, formed a privileged caste that was to remain forever separate from the rest of the French.

Such is our history under the kings of the first dynasty. It is one of the periods in which the formation of a national spirit encountered the greatest obstacles, owing to the number, harshness, and violence of the opposing interests.

The institutions of Charlemagne gave legal sanction to distinctions of orders which until then had existed only in fact among the French. To form national assemblies, he divided the nation into three classes: the clergy, the nobility, and the people, a distinction which, it would seem, was to be eternal and to form an invincible obstacle to the union [163] of interests and to the birth of a public spirit. At the same time, he allowed seigneurial courts and benefices to continue. Nevertheless, he considerably modified the effect of these anarchic institutions. He curbed the abuses of judicial power exercised by the lords and, through his example, encouraged them to renounce the most odious of the rights established on their lands. By including the people in national assemblies, he sought to bring them closer to the great lords, to enlighten them as to their rights, and to rekindle within them the sense of their dignity and independence. Had our ancestors been less brutalized by slavery and poverty, perhaps this great man would have succeeded in restoring to them some virtue and inspiring them with some patriotism. But although he spared them many abuses, and although in certain respects his institutions were quite mild, they were still too strong for the French of that time, and they proved incapable of bearing them. On the other hand, the successors of this prince, far from supporting his work, only hastened its ruin through their weakness and incompetence.

As soon as disorders reemerged, with renewed violence, the nobles cast off all forms of subordination, and the people fell back into their former servitude. It was then that the monstrous system of feudalism took shape, a system that gave a semblance of order to the anarchy reigning among the lords, and which, of all the particular tyrannies, formed an immense chain of oppression, the [164] first link of which was attached to the throne, and which descended to weigh down even the lowest classes of the people. In this system, the King was the suzerain lord of the great men who held their fiefs from the crown, and these great men were his direct vassals; the King’s vassals in turn were suzerains of lesser nobles, to whom they granted lands as fiefs; these latter were again suzerains of new vassals to whom they had likewise ceded fiefs, and so on. This arrangement, which seemed destined to unite all the holders of fiefs by placing them in a sort of hierarchical dependence, not only further separated them from the people by tightening the chains upon the latter, but also became a new cause of dissension among themselves. The great vassals of the crown, emboldened by the weakness of the kings, made a mockery of the obligations imposed by their feudal engagements; the lesser vassals imitated their example and sought as well to become independent of their suzerains; they all set themselves up as sovereigns on their own lands; the yoke they imposed on their subjects grew heavier than ever; they formed coalitions, they waged war against the King, and against each other, they constantly encroached on one another's domains, in a word, the conduct of our petty lords of the time was a complete parody of that of so many great princes who, in all ages, have thought only of maintaining servitude within their states and waging war abroad to enlarge their suzerainty.

[165]

This state of violence, dissension, and brigandage lasted as long as the Carolingian dynasty, whose fall it brought about, and for two more centuries, the population of France consisted only of two equally degraded classes, some degraded by the tyranny they exercised, others by the yoke they bore, and all equally incapable of forming any idea of a (patrie) homeland or the public good. One could compare this period and the one preceding it, in terms of the utter absence of national spirit, only to our own era, an era in which the French, though outwardly more united, are perhaps in reality even more divided, and in which egoism, which separates men even more effectively than anarchy and civil war, has succeeded in making every individual the secretly irreconcilable enemy of all whose interests conflict with his own.

Feudalism persisted for a long time under the kings of the third dynasty, it even grew stronger under the early Capetians. Its code took shape then; the lords, weary of settling their disputes by the sword, established customs to regulate their relations with one another and with their vassals. These customs confirmed all their previous usurpations. They secured their independence from the king and the subjugation of their subjects; they invested them, within their domains, with all the attributes of sovereignty: legislative power, judicial authority, the right to mint coins, the right to make war or peace at will, and to compel their vassals and subjects [166] to take up arms for their quarrels, in short, they organized within the state countless mini-states and entangled interests in a thousand ways.

We say that the lords had the right of justice. Since they knew only how to fight and understood nothing of the science of law, they introduced into their feudal courts the monstrous practice of judicial duels and other ordeals known as judgments of God, a practice that placed right in physical strength, and crime or innocence in the way one endured equally absurd and barbaric trials. This completed the demoralization of the spirit (minds) and closed them, for centuries, to all ideas of legislation, justice, and order, without which there can be neither homeland nor patriotism. The practice of judicial duels had the additional effect of maintaining barbaric manners and a culture of fighting; it remained a constant cause of quarrels, banditry, and division among the citizens.

It is this practice of judicial duels that gave birth to that infamous notion of the point of honor, which has ever since been one of the chief rules of conduct for the French. Pride and ferocity dictated its earliest rules. Vanity of rank determined what would count as an insult, and the barbarism of manners dictated how it would be avenged. Since commoners or villeins, in legal disputes, could only use a staff, while gentlemen used their swords, to strike [167] someone with a staff was to commit an injury that demanded blood, because it meant treating him like a commoner. Since only commoners fought with uncovered faces, to slap a man was an insult that could only be washed away with blood, because it was again treating him like a commoner. Thus, according to the principles of the point of honor, an offense is an offense to the person receiving it only because he is treated like a commoner. From this it is clear that the point of honor is nothing but a false and exaggerated sentiment of the superiority of rank, that it reveals, with obnoxious intensity, the contempt of the upper-classes for those of lower classes, and that it establishes insurmountable barriers between citizens. That is all I will say about it here: I will later show how this sentiment, so quick to be outraged by a trivial word, tolerates things far more dishonorable, how many base acts it can coexist with, and in how many other respects it harms the public spirit.

The order of chivalry, which originated under the early Capetians, greatly encouraged the use of duels and, from this point of view, was, like judicial combat, a cause of disorder and division among the French. It extended the code of the point of honor and enriched it with some useful and noble principles; but it also introduced several false or bizarre rules and preserved within it the antisocial principle on which it was based. — The gallantry [168] that the knights invented, and which became one of their foremost duties, was a puerile and exaggerated sentiment that distorted their minds, diminished their souls, led them to perform with great flourish a thousand trivialities, many foolish extravagances, sometimes criminal acts, and gave their most heroic feats a motive that was almost always ridiculous. I will show elsewhere more clearly the influence that gallantry, and the refinement of manners that it gave us, have had on our public spirit.

Religion had not been the least of the factors which, since the beginning of the monarchy, helped prevent the birth of public spirit in France. The clergy had at first preached passive obedience; soon after, it gave the example of the most unbridled insubordination. Always orthodox in belief, it showed itself even more depraved in morals, and its conduct presented the monstrous alliance of purity of faith with all the vices of the soul. It preached control of the body and set the example of a licentious life; it preached humility and exercised with pride a usurped domination; it preached contempt for riches, and its insatiable greed threatened France with universal usurpation. [4] There were no efforts it did not make, no means it did not employ, to grab all the wealth of the State. It persuaded the people that there were no crimes so heinous they could not be expiated by gifts to the churches. [5] It got heaven to intervene directly in the establishment of the [169] tithe, [6] and ensured its payment by filling the souls of the faithful with pointless terrors. It instituted penance as a means of expiation, and these penances became a commercial resource for the monks, [7] who undertook them for money; finally, it employed the force of arms and stained itself with blood in order to acquire new riches or retain those it had plundered from the citizens. Thus, to become rich and powerful, it gave rise to the most pernicious moral errors and simultaneously reinforced ignorance, barbarity of manners, and the habit of every vice; causes which, as we can see, had the most harmful influence on public spirit.

Plundered of its property by Charles Martel, compensated for its losses by Charlemagne, but plundered a second time by the nobles under that prince’s successors, the clergy lost its preeminence during the second dynasty. It schemed to recover it under the early Capetians. Judicial duels offered the opportunity. It loudly condemned them in the name of heaven; and under the pretext that in every trial one of the litigants defends an injustice, that every injustice is a sin, that every sin concerns religion, and that everything concerning religion falls within the competence of its ministers, it usurped from the lords the right to render justice, and this right soon became for it a fertile source of wealth and authority. In this way, it succeeded in forming once again a power within the State, and thus a [170] new source of division in sentiments and interests.

This skillful usurpation by the clergy encouraged another, even more remarkable, on the part of the popes. As the temporal power they had acquired since Charlemagne had allowed them to assert absolute authority over the bishops of all Catholic countries, they demanded that all judgments made by the ecclesiastical courts of the kingdom be submitted for their review, and they thus became among us the supreme judges of all affairs and the highest magistrates of the State. It was then in particular that the ultramontane spirit began to reign in France, and we know how little that spirit was suited to the formation of citizens.

Such, up to the beginning of the twelfth century, are the causes that opposed the unification of sentiments, interests, and opinions, and the birth of a patriotic spirit in France. Here begins a great revolution in government, a revolution carried out over nearly five centuries with as much skill as perseverance, and which ends by transferring into the hands of the successor of Capet all the power that the lords had seized from the descendants of Charlemagne. In this slow transition from feudal anarchy to the almost absolute authority of our later kings, beneficial changes were made in our institutions; yet they were far from taking a direction suited to the formation of citizens. Previously useful to the tyranny [171] of the nobles, they now served only to protect the power of kings, and left the nation in its dependency, its apathy, and its eternal indifference to itself.

However, alongside this revolution in government and political institutions, another gradually unfolded in opinions and manners, a revolution whose terrible climax, after six centuries, was to throw out the descendants of the Capets from the throne, to raise the long-oppressed Third Estate above the nobles and the kings, and to invest it in turn with sovereign power; a revolution accomplished in the name of the homeland and the public good, and one whose results were perhaps as damaging to morals and to patriotism as the ones that came before.

I will briefly follow, in a second article, the progress of both these matters. I will show the obstacles that the formation of public spirit continues to encounter during the course of their development. I will show the state in which the last government left our morals. I will expose, without disguising the fact, the particular degradation of most public officials, [8] and the impossibility that anything solid can be established as long as they make the care of their own fortunes their first duty. Finally, I will demonstrate that a faithful observance of the laws is the only regime capable of giving us a truly national character and of allowing us at last to enjoy real and lasting happiness.

O.

Endnotes

[1] Compare with Benjamin Constant's lecture on “De la liberté des anciens comparée à celle des modernes" which he gave at the Athénée royal in Paris” in 1819. It was published in Collection complète des ouvrages publiés sur le gouvernement représentatif et la constitution actuelle de la France, formant une espèce de cours de politique constitutionnelle. Quatrième volume, septième partie. (Paris/Rouen: Béchet, 1820), pp. 238-274. Online.

[2] He says "les gouvernans" and "les gouvernés".

[3] He says "l’opprimé" and "l'oppresseur".

[4] (Note by Dunoyer.) Every man who died without giving a portion of his property to the Church, which was called dying déconfès, was deprived of communion and burial. If one died without making a will, the relatives had to have the bishop appoint, jointly with them, arbiters to determine what the deceased ought to have given, in case he had made a will. One could not lie together on the first night of the wedding, nor even on the two following nights, without having bought permission: it was indeed those three nights that had to be chosen, for as to the others, one would not have paid much money. Esprit des lois, Book 28, Chapter 48.

[5] (Note by Dunoyer.) … Alms were especially the penance of the rich. They erased their sins by increasing the wealth of a church, or by founding a monastery. When Charlemagne gave the Exarchate of Ravenna to the pope, he believed he was working for his salvation. Histoire moderne de Condillac, Book 2, Chapter 1.

[6] (Note by Dunoyer.) The clergy preached in support of the tithe; they preached it in the name of Saint Peter; the monks even made Jesus Christ speak in its favor. They forged a letter that the Savior was writing to the faithful, in which he threatened the pagans, the sorcerers, and those who did not pay the tithe, to strike their fields with barrenness, to overwhelm them with infirmities, and to send into their houses winged serpents who would devour the breasts of their wives. Ibid.

[7] (Note by Dunoyer.) … Penances became a source of income for the monks, who undertook to perform them in exchange for a certain sum. Thus, a rich man sinned, and a monk administered the discipline to himself. Ibid.

[8] He says "les fonctionnaires publics".