CHARLES DUNOYER,

"On Public Spirit in France, and particularly on the Spirit of Public Officials" (Part 2)

Le Censeur (August 1814)

Charles Dunoyer (1786-1862) |

|

[Created: 11 May, 2025]

[Updated: 11 May, 2025] |

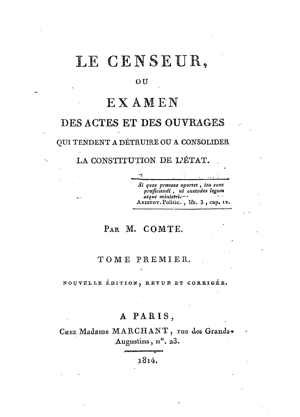

Source

, "On Public Spirit in France, and particularly on the Spirit of Public Officials" (Part 2), Le Censeur. T. 1, No. 6. (3-14 August 1814), pp. 217-29.http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Comte/CenseurAnthology/EnglishTranslation/C1-03-Dunoyer_PublicSpirit2_T1_1814.html

Charles Dunoyer, "On Public Spirit in France, and particularly on the Spirit of Public Officials" (Part 2), Le Censeur. T. 1, No. 6. (3-14 August 1814), pp. 217-29.

A translation of Charles Dunoyer, "De L’esprit public en France, et particulièrement de l’esprit des fonctionnaires publics," Le Censeur. T. 1, No. 6. (3-14 August 1814), pp. 217-29.

This is part of an Anthology (in French originally) of writings by Charles Comte (1782-1837), Charles Dunoyer (1786-1862), and others from their journal Le Censeur (1814-15) [ToC] and Le Censeur européen (1817-1819) [ToC].

See also other works by Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer.

[217]

"On Public Spirit in France, and particularly on the Spirit of Public Officials" [1]↩

France, during the reign of feudalism, presented, from a certain point of view, the aspect which Europe presents today. Its kings, reduced to a mere right of suzerainty that the insubordination of the lords rendered even illusory, exercised real power only in their capacity as lords over the inhabitants of their private domains. Each province, each seigneury formed a separate state, and all these small states were, either in themselves or in relation to one another, in a situation roughly similar to that in which the various European states have long found themselves. The authority of the lords rested, as [218] that of the kings did later, on the sovereignty of their jurisdiction, on the passive obedience of their subjects, on the balance existing between the powers of the principal fiefs, a balance which ensured the independence of the lesser lords in much the same way that the balance established between the great powers of Europe protects the authority of the lesser princes. A powerful lord who might have wished to become sole ruler of France would thus have had to undertake roughly what a prince aspiring today to universal monarchy would have to undertake in Europe.

This task did not deter the policy of the descendants of Hugh Capet. They focused on understanding the flaws of the feudal system, and they skillfully exploited them to destroy all of its supports. They took advantage of the state of distress and want in which the lords found themselves, as a result of their domestic wars, to persuade them, by their own example, to emancipate, for a sum of money, the inhabitants of their lands, and to sell them communal charters; they took advantage of the state of servitude and poverty in which they had always kept them, to persuade them to place themselves under royal protection, and to take the king as guarantor of the commitments the lords made to them. They used the rivalries between the lords to make them all subject to their special courts, and to have judgments carried out by some lords which was used to strip others of their credit and [219] wealth. The barbarity of judicial duels offered them the most fortunate pretext for establishing procedures for the conduct of trials in writing and with witnesses, which disgusted the lords at the thought of having to take on the role of judge; the doctrine of appeals to the suzerain, which led all cases gradually to the king’s supreme court; the bailiwicks, which were tasked with reviewing the judgments of the lords, and which, through the clever doctrine of royal cases, completed the ruin of the seigneurial courts. They justified themselves by the disorder caused by the oddities and contradictions of the customs established in the various seigneuries, to enact general laws, and they enlisted the lords’ greed in the observance of these laws by granting them the proceeds of fines pronounced against violators. Taking advantage of the discontent aroused by the successive debasements of coinage imposed by the lords, they stripped them of the right to continue minting them. In short, there was no abuse from which they did not cleverly draw some benefit to extend their authority, and in the progress it made, they found the means to ensure it advanced further each day.

As the power of the kings expanded, the quarrels among the lords lost their intensity, the people’s servitude became less harsh, and institutions and manners ceased to be as barbaric. However, this change did not favor the development of public spirit, because the kings were more concerned with making subjects than citizens. Far from seeking to unite the French, they used the very clever skill of dividing them in order [220] to subjugate them more effectively. Louis the Fat armed the communes against the lords; Philip Augustus set the lesser nobility against the great lords; Philip the Fair, aware of the resentment that clergy, lords, and communes bore toward one another, summoned the Estates-General, to which he called the three orders, and he brought them together only to divide them more thoroughly. While rejecting all their demands on the pretext that they were not in agreement, he sold to each, at a high price, charters that served only to intensify their mutual hatreds. Finally, at the same time that the kings maintained the disunity of the different classes within France, they sought to bring them all under their power, or rather, they divided them only in order to make them all equally interested in currying favor with them and seeking their protection: thus, at the Estates-General convened by Philip the Fair, the three orders, in the midst of their disagreements, made equal efforts to win over this prince and obtain his support, so that the Nation seemed to have been assembled only to acknowledge his supreme power. The policy the kings used to extend their authority thus posed no less of an obstacle to the birth and progress of patriotism through the jealousies and hatreds it fomented among the different orders of citizens, than through the spirit of servitude it inspired in them all.

This cunning approach was too useful to the authority of the kings for them not to [221] persevere with it. Already in the reign of Philip the Fair, it had transferred into their hands the highest prerogatives of sovereignty, legislative power, judicial power, the exclusive right to mint coins, to make peace and war, to recruit armies, along with the means of having them regularly in their pay. It was by means of the same tactic of opposing bishops to popes and popes to bishops in turn that they had succeeded in almost entirely ruining the power of both, and in stripping them of the right of justice which they had usurped from the lords at the beginning of the reigning dynasty; it was by this conduct, in a word, that they had succeeded in wresting from the lords nearly all their prerogatives, in seizing all powers, in securing recognition of their authority from citizens of all classes, and in having in France hardly anything but subjects, even among their most powerful vassals.

To preserve their power and to make it gain further ground, they used the same means they had employed to acquire it. They turned to its profit even those things that seemed most likely to destroy it. The reckless, capricious, and harsh administration of the early Valois, the violent rumours it aroused, and the civil war it eventually ignited, served, in the end, only to render their authority more absolute. If the nation wished to take steps to recover its rights, being insufficiently enlightened to do this wisely, it was turned against them to its own misfortune and disgrace; and [222] its resistance to oppression was no less harmful to its liberty than its submission to arbitrary power.

Soon the great lords, who had been completely defeated by the ascendency of royal power and who no longer dared to exercise sovereignty within their own domains,changed their views and conduct, and gave their ambition an entirely new direction. They aspired only to extend and strengthen the power of the kings, which they had made so many efforts to destroy, and to become their ministers after having been for so long their rivals; hoping thereby no doubt to exercise in their name the authority they had lost, and perhaps to regain it. At the same time, the clergy broke away from the nation, and conspired with the great lords to increase the authority of the kings, from whom alone henceforth they could hope for honors and wealth.

However, while the great lords and the clergy acted in concert to extend the royal prerogative, a humble group of magistrates, envious of their influence, dared to conceive the idea of halting its progress and taking over one of its most important functions. The Parlement, which the kings had established solely to judge lawsuits, claimed the right of subjecting the laws to its approval and to the formality of registering them as a condition without which they could have no force. They were able to do this by using with skill the esteem it had earned by its learning, the prestige that the kings had conferred upon it by holding the "lits de justice" (the sitting of judges/court) in his presence and ruling upon the greatest affairs of state, the popularity it had acquired by receiving petitions from individuals and provinces who appealed to it against arbitrary acts of authority, and especially [223] the habit ministers had formed of having their ordinances published by it, and of getting them transcribed into its registers to give them greater force. It thereby associated itself with legislative power, and succeeded in having this usurpation recognized. Later, it also succeeded in subjecting the great lords to its jurisdiction and in having itself acknowledged as the Court of Peers of the kingdom. These two high prerogative powers placed it in a position to struggle against the great lords to its benefit; but this struggle, in which both parties cloaked themselves in the king’s name, and from which the king skillfully took advantage to keep both in check, served only to consolidate his power; and the nation, which the Parlement did not defend in good faith, and whose interest was sacrificed to all its ambitions, found itself more surely oppressed than ever, and each day further away from possessing any public spirit.

Such was the state of France at the end of the 15th century. At that time, the princes of Europe gave their politics an entirely new direction, and this revolution succeeded in making the authority of our kings absolute.

Feudal anarchy had reigned in all the states of Europe just as in France, and everywhere it had inflicted the same damage on royal prerogative. As long as kings were forced to struggle against their vassals and to contest their authority, they [224] remained neighbors without thinking of making war on one another; but as soon as they succeeded in recovering their power and establishing it within their states, they wanted to make themselves great abroad, and to expand their empires by force of arms. The successes that France, Spain, and Austria achieved in turn during the war of conquest that Charles VIII conducted in Italy suddenly gave rise in nearly all the crowned heads to the mad passion for conquest.

“Miserable ideas of fortune, of aggrandizement, and of defense were conceived,” says Thouret, “and all Europe was swept away by the rapid movement of a ruinous prejudice which has neither been suspended nor calmed by two centuries of fruitless wars.”

This revolution gave rise to a kind of public spirit in France; but it took such a false direction, it so greatly reinforced our chains, and made the birth of true patriotism so difficult, that it might have been better for the nation had it not emerged from its habitual state of torpor and apathy. Far from this being the case, the nation shared in the delirium of its leaders and allowed itself to be swept away entirely by the shallowest ideas of grandeur and glory. It believed its honor to be bound up in seeing its kings dominate foreign nations. It seemed to seek to elevate them to a very high level in order to make its dependence less humiliating, even to cloak itself in a certain splendor, and to console itself for its domestic servitude by having a great empire beyond its borders. This moral condition, which disposed the nation to obedience through admiration, [225] and thus ennobled its dependence, was suited only to make it ever less capable of patriotism. On the other hand, war, by putting at the disposal of our kings large armies composed of men accustomed to the most blind obedience, it put into their hands a terrible instrument, which they could use to subject France as they pleased. The spirit of war and conquest [2] thus offered our princes two equally powerful means of making their authority absolute. Accordingly, they gave all their attention to sustaining war; they placed military virtues above all other virtues; they cast upon them the brightest luster; they were the first to set an example for it; and nearly all sought to make the nation triumph abroad in order to subjugate it more easily at home.

This new policy advanced royal authority so greatly that, already under the reign of Francis I, it crushed everything around it and encountered almost no obstacles. This prince was powerful enough to treat all the orders of his kingdom as a master would. He dismissed without consequence the great men who cast a shadow over him; he repressed the ambition of the Parlement, reminded it of its origin, and forced it to return to the purpose of its creation; he wrested from the popes the power they had usurped in France to appoint bishops and abbots; he had at his disposal, under cover of that power, the prelates of his kingdom, and assured himself through them of the submission of the entire clergy; [226] in a word, he held all the French equally in dependence and gave an entirely new force to what has since been called the spirit of the monarchy, a spirit which was certainly anything but patriotism.

The successors of this prince did not know how to retain a power that would have been so easy for them to preserve. Their extreme weakness gave rise to civil wars that threatened to drive their family from the throne—wars kindled by fanaticism in the service of ambition, and which, for nearly half a century, caused dreadful divisions in France without improving public spirit.

The doctrines of Luther had entered the kingdom during the reign of Francis I, and the protection that this prince extended to it in Germany contributed no less than the depravity of his court to gaining it some adherents in France. As the contagion could not be stopped by the example of morals and piety, it was necessary to oppose it with fire and sword, and the violence of these means served only to make it more active. The successors of Francis wished to combat the evil in the same way, and like him, they did nothing but spread and intensify it. Persecution made it gain ground more rapidly each day; it inflamed equally those who inflicted it and those who suffered it; and France found itself divided into two enemy nations, equally eager to tear each other apart. Factions took advantage of these conditions to try to seize power. [227] The Guises placed themselves at the head of the Catholics; Condé became the lead of the Huguenots; the leaders of both parties vied at first to wrest the sceptre from the hands of the Valois; later the Guises sought to push the Bourbons away from the now vacant throne to which heredity called them; and while the people believed they were shedding their blood for religion, they served only the ambition of a few great men. In the midst of the excesses to which they were driven, their disordered minds retained no idea of homeland or of public good. If a few men, who remained calm in the midst of the general frenzy, dared to consider a reconciliation between Catholics and Reformers, and to try to make their bloody quarrels be used for the establishment of liberty and public happiness, their party became an object of horror and scorn for the other two, and the nation emerged from its pious frenzy only to fall once again, under Henry IV, into the languor of servitude.

This prince made use of the same policy that his predecessors had so skillfully exploited to restore royal authority. He took advantage of the divisions among the Leaguers to conquer the throne; he took advantage of the rivalries among the great lords to bring them all back into obedience; he left, in the famous edict intended to pacify the two religious parties, some grounds for anxiety and discontent for both sides, in order to make them both feel the necessity of his protection and the need to seek it; and he succeeded in making his power as absolute as that of Francis I. Thus, although Henry [228] sincerely desired the good of his people, the blind submission he required of them did not allow public spirit to develop under his reign. He allowed all the principles of disorder that had accumulated in the State since the origin of the monarchy to persist: the mutual hostility of the three orders, the ambition and rivalries of the great lords, an equal disposition of the people to servitude and revolt, the particular ambition of the Parlement, and the poorly extinguished hatreds born of religious quarrels.

All these elements of disorder fermented simultaneously under the regency of Marie de Médicis and during the early years of the reign of Louis XIII; and they would inevitably have produced new civil wars, had there not appeared in the king’s council a man capable not of destroying them—for despotism is always itself a more or less immediate cause of anarchy—but at least of halting their development.

The Edict of Nantes inspired in the Calvinists anxieties that kept them in a perpetual state of insurrection. Richelieu calmed their agitation by undermining their strength; he thus deprived the great nobles of the only support that remained for their ambition; he broke all those he could not bend, or forced them into exile; he deeply humiliated the Parlement; he enslaved minds both by the charm of the arts and by the terror of his tortures; he overwhelmed the nation with all the ascendency that he gave it over the other powers of Europe, and bowed it so thoroughly beneath [229] despotism that after his death it continued to be docile under the uncertain hand of Louis XIII, and that the seeds of discord it still harbored could produce, during the minority of Louis XIV, nothing but the ridiculous war of the Fronde.

The reign of this last prince is, in many respects, only a continuation of Richelieu’s ministry. His despotism is less grim, but no less forceful. Never has a prince held his people in chains at once more brilliant and more unbreakable; never has absolute power appeared under forms more grand, more noble, more seductive—I would almost dare say more corrupting; and so the nation under this prince lost any idea of independence, and the will of the monarch became for it the supreme law.

To be continued in a future issue.

D….r.

Notes↩

[1] (Note by Dunoyer.) See the fourth installment, page 156.

[2] Compare the essay by Benjamin Constant, De l'esprit de conquête et de l'usurpation, dans leurs rapports avec la civilisation européenne. Quatrième édition (Paris: H. Nicolle, 1814). Online.