Jean-Baptiste Say, A Treatise on Political Economy (1803, 1819, 1821)

|

|

| Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832) |

This is part of a collection of works by Jean-Baptiste Say.

Source

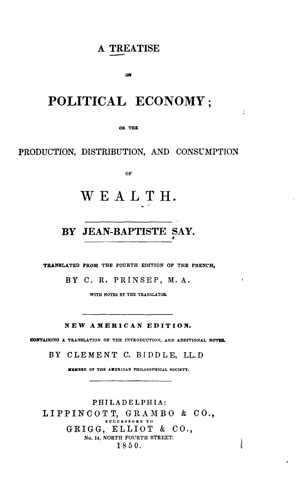

Jean-Baptiste Say, A Treatise on Political Economy; or the Production, Distribution, and Consumption of Wealth. Translated from the Fourth Edition of the French, by C. R. Prinsep with Notes by the Translator. New American Edition of the Introduction, and Additional Notes by Clement C. Biddle (Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co., 1850). 6th edition.

See also the facs. PDF of the original 1821 edition [vol.1 and vol.2] and the 6th edtion of 1850 [facs. PDF]

This is a translation of the 4th French edition of 1819 [facs. PDF of vol.1 and vol.2]. The 1st edtion was in 1803 [facs. PDF of vol. 1 and vol. 2]. The "final" definitive edition was that of 1841: Jean-Baptiste Say,Traité d’économie politique ou simple exposition de la manière dont se forment, se distribuent et se consomment les richesses. Sixième édition entièrement revue par l'auteur, et publiée sur les manuscrits qu'il a laissés, par Horace Say, son fils (Paris: Guillaumin, 1841). [HTML and facs. PDF]

Table of Contents

- ADVERTISEMENT by THE AMERICAN EDITOR, to the SIXTH EDITION.

- ADVERTISEMENT by THE AMERICAN EDITOR, TO THE FIFTH EDITION.

- Introduction

- BOOK I: OF THE PRODUCTION OF WEALTH.

- CHAPTER I.: OF WHAT IS TO BE UNDERSTOOD BY THE TERM, PRODUCTION.

- CHAPTER II.: OF THE DIFFERENT KINDS OF INDUSTRY, AND THE MODE IN WHICH THEY CONCUR IN PRODUCTION.

- CHAPTER III: OF THE NATURE OF CAPITAL, AND THE MODE IN WHICH IT CONCURS IN THE BUSINESS OF PRODUCTION.

- CHAPTER IV: ON NATURAL AGENTS THAT ASSIST IN THE PRODUCTION OF WEALTH, AND SPECIALLY OF LAND.

- CHAPTER V: ON THE MODE IN WHICH INDUSTRY, CAPITAL, AND NATURAL AGENTS UNITE IN PRODUCTION.

- CHAPTER VI: OF OPERATIONS ALIKE COMMON TO ALL BRANCHES OF INDUSTRY.

- CHAPTER VII: OF THE LABOUR OF MANKIND, OF NATURE, AND OF MACHINERY RESPECTIVELY.

- CHAPTER VIII: OF THE ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES RESULTING FROM DIVISION OF LABOUR, AND OF THE EXTENT TO WHICH IT MAY BE CARRIED.

- CHAPTER IX: OF THE DIFFERENT METHODS OF EMPLOYING COMMERCIAL INDUSTRY, AND THE MODE IN WHICH THEY CONCUR IN PRODUCTION.

- CHAPTER X: OF THE TRANSFORMATIONS UNDERGONE BY CAPITAL IN THE PROGRESS OF PRODUCTION

- CHAPTER XI: OF THE FORMATION AND MULTIPLICATION OF CAPITAL.

- CHAPTER XII: OF UNPRODUCTIVE CAPITAL

- CHAPTER XIII: OF IMMATERIAL PRODUCTS, OR VALUES CONSUMED AT THE MOMENT OF PRODUCTION.

- CHAPTER XIV: OF THE RIGHT OF PROPERTY.

- CHAPTER XV: OF THE DEMAND OR MARKET FOR PRODUCTS.

- CHAPTER XVI: OF THE BENEFITS RESULTING FROM THE QUICK CIRCULATION OF MONEY AND COMMODITIES.

- CHAPTER XVII: OF THE EFFECT OF GOVERNMENT REGULATIONS INTENDED TO INFLUENCE PRODUCTION.

- CHAPTER XVIII: OF THE EFFECT UPON NATIONAL WEALTH, RESULTING FROM THE PRODUCTIVE EFFORTS OF PUBLIC AUTHORITY.

- CHAPTER XIX: OF COLONIES AND THEIR PRODUCTS.

- CHAPTER XX: OF TEMPORARY AND PERMANENT EMIGRATION, CONSIDERED IN REFERENCE TO NATIONAL WEALTH.

- CHAPTER XXI: OF THE NATURE AND USES OF MONEY.

- SECTION I.: General Remarks.

- SECTION II.: Of the Material of Money.

- SECTION III.: Of the Accession of Value a Commodity receives by being Vested with the Character of Money.

- SECTION IV.: Of the Utility of Coinage, and of the Charge of its Execution.

- SECTION V.: Of Alterations of the Standard Money.

- SECTION VI.: Of the reason why Money is neither a Sign nor a Measure.

- SECTION VII.: Of a Peculiarity that should be attended to, in estimating the Sums mentioned in History.

- SECTION VIII.: Of the Absence of any fixed ratio of Value between one Metal and another.

- SECTION IX.: Of Money as it ought to be.

- SECTION X.: Of a Copper and Base Metal83 Coinage.

- SECTION XI.: Of the preferable Form of Coined Money.

- SECTION XII.: Of the Party, on whom the Loss of the Coin by Wear should properly fall

- CHAPTER XXII: OF SIGNS OR REPRESENTATIVES OF MONEY.

- BOOK II: OF THE DISTRIBUTION OF WEALTH

- CHAPTER I: OF THE BASIS OF VALUE; AND OF SUPPLY AND DEMAND.

- CHAPTER II: THE SOURCES OF REVENUE.

- CHAPTER III: OF REAL AND RELATIVE VARIATION OF PRICE.

- CHAPTER IV: OF NOMINAL VARIATION OF PRICE, AND OF THE PECULIAR VALUE OF BULLION AND OF COIN.

- CHAPTER V: OF THE MANNER IN WHICH REVENUE IS DISTRIBUTED AMONGST SOCIETY.

- CHAPTER VI: OF WHAT BRANCHES OF PRODUCTION YIELD THE MOST LIBERAL RECOMPENSE TO PRODUCTIVE AGENCY.

- CHAPTER VII: OF THE REVENUE OF INDUSTRY

- SECTION I.: Of the Profits of Industry in general.

- SECTION II.: Of the Profits of the Man of Science.

- SECTION III.: Of the Profits of the Master-agent, or Adventurer, in Industry.

- SECTION IV.: Of the Profits of the Operative Labourer.47

- SECTION V.: Of the Independence accruing to the Moderns from the Advancement of Industry.

- CHAPTER VIII: OF THE REVENUE OF CAPITAL.

- CHAPTER IX: OF THE REVENUE OF LAND.

- CHAPTER X: OF THE EFFECT OF REVENUE DERIVED BY ONE NATION FROM ANOTHER.

- CHAPTER XI: OF THE MODE IN WHICH THE QUANTITY OF THE PRODUCT AFFECTS POPULATION.

- BOOK III: OF THE CONSUMPTION OF WEALTH

- CHAPTER I: OF THE DIFFERENT KINDS OF CONSUMPTION.

- CHAPTER II: OF THE EFFECT OF CONSUMPTION IN GENERAL.

- CHAPTER III: OF THE EFFECT OF PRODUCTIVE CONSUMPTION.

- CHAPTER IV: OF THE EFFECT OF UNPRODUCTIVE CONSUMPTION IN GENERAL.

- CHAPTER V: OF INDIVIDUAL CONSUMPTION—ITS MOTIVES AND ITS EFFECTS.

- CHAPTER VI: ON PUBLIC CONSUMPTION

- SECTION I.: Of the Nature and general Effect of Public Consumption.

- SECTION II.: Of the principal Objects of National Expenditure.

- Of the Charge of Civil and Judicial Administration.

- Of Charges, Military and Naval.

- Of the Charges of Public Instruction.

- Of the Charges of Public Benevolent Institutions.

- Of the Charges of Public Edifices and Works.

- CHAPTER VII: OF THE ACTUAL CONTRIBUTORS TO PUBLIC CONSUMPTION.

- CHAPTER VIII: OF TAXATION.

- CHAPTER IX: OF NATIONAL DEBT.

- APPENDIX A: A Table, Showing the Result of Value Lent to the State.

- APPENDIX B: A table, showing the comparative condition of France, Great Britain and Ireland, and the United States of America, in respect to Population, Debt, and Taxation, at the close of the year 1831.

ADVERTISEMENT by THE AMERICAN EDITOR to the SIXTH EDITION. ↩

A NEW edition of this translation of the popular treatise of M. Say having been called for, the five previous American editions being entirely out of print, the editor has endeavoured to render the work more deserving of the favour it has received, by subjecting every part of it to a careful revision. As the translation of Mr. Prinsep was made in the year 1821, from an earlier edition of the original treatise, namely, the fourth, which had not received the last corrections and improvements of the author, wherever an essential principle had been involved in obscurity, or an error had crept in, which had been subsequently cleared up and removed, the American editor has, in this impression, reconciled the language of the text and notes to the fifth improved edition, published in 1826, the last which M. Say lived to give to the world. It has not, however, been deemed necessary to extend these alterations in the translation any further than to the correction of such discrepancies and errors as are here alluded to; and the editor has not ventured to recast the translation, as given by Mr. Prinsep, merely with a view to accommodate its phraseology, in point of neatness of expression or diction, to the last touches of the author. The translation of Mr. Prinsep, the editor must again be permitted to observe, has been executed with sufficient fidelity, and with considerable spirit and elegance; and in his opinion it could not be much improved by even remoulding it after the last edition. The translation of the introduction, given by the present editor, has received various verbal corrections; and such alterations and additions as were introduced by the author into his fifth edition, will now be found translated.

It is, moreover, proper to state, that at the suggestion of the American proprietors and publishers of this edition of the work, the French moneys, weights and measures, throughout the text and notes, have been converted into the current coins, weights and measures of the United States, when the context strictly required it by a rigorous reduction, and when merely assumed as a politico-arithmetical illustration, by a simple approximation to a nearly equivalent quantity of our own coins, weights or measures. This has been done to render the work as extensively useful as possible, and will, no doubt, make the author's general principles and reasonings more easily comprehended, as well as more readily remembered, by the American student of political economy.

Many new notes, it will be seen, have been added by the American editor, in further illustration or correction of those portions of the text which still required elucidation. The statistical data now incorporated in these notes, have been brought down to the most recent period, both in this country and in Europe. No pains have been spared in getting access to authentic channels of information, and the American editor trusts that the present edition will be found much improved throughout.

The death of M. Say took place, in Paris, during the third week of November, 1832, on which occasion, according to the statements in the French journals, such funeral honours were paid to his memory as are due to eminent personages, and Odilon-Barrot, de Sacy, de Laborde, Blanqui, and Charles Dupin, his distinguished countrymen and admirers, pronounced discourses at the interment in the cemetery of Pêre Lachaise.

The account of his decease, here subjoined, is taken from the London Political Examiner of the 25th of November, 1832, and is from the pen of its able editor, Mr. Fonblanque, one of the most powerful political writers in England. Mr. Fonblanque, it appears, was the personal friend, as well as the warm admirer, of the genius and writings of M. Say, and was well qualified to appreciate his high intellectual endowments, his profound knowledge and political wisdom, his manly independence, his mild yet dignified consistency of character, and above all, his rare and shining private virtues. There hardly could be a more interesting and instructive task assigned to the philosophical biographer, than a faithful portraiture of the life and labours of this illustrious man, which were so ardently and efficiently devoted to the advancement of the happiness and prosperity of his fellow-men. Perhaps the writings of no authors, however great their celebrity may be, are exerting a more powerful and enduring influence on the well-being of the people of Europe and America, than those of Adam Smith, and John Baptiste Say.

"France has this week lost another of her most distinguished writers and citizens, the celebrated political economist, M. Say. The invaluable branch of knowledge to which the greatest of his intellectual exertions were devoted, is indebted to him, amongst others, for those great and all-pervading truths which have elevated it to the rank of a science; and to him, far more than to any others, for its popularization and diffusion. Nor was M. Say a mere political economist; else had he been necessarily a bad one. He knew that a subject so 'immersed in matter,' (to use the fine expression of Lord Bacon,) as a nation's prosperity, must be looked at on many sides, in order to be seen rightly even on one. M. Say was one of the most accomplished minds of his age and country. Though he had given his chief attention to one particular aspect of human affairs, all their aspects were interesting to him; not one was excluded from his survey. His private life was a model of the domestic virtues. From the time when, with Chamfort and Ginguenê, he founded the Decade Philosophique, the first work which attempted to revive literary and scientific pursuits during the storms of the French Revolution—alike when courted by Napoleon, and when persecuted by him (he was expelled from the Tribunat for presuming to have an independent opinion); unchanged equally during the sixteen years of the Bourbons, and the two of Louis Philippe—he passed unsullied through all the trials and temptations which have left a stain on every man of feeble virtue among his conspicuous contemporaries. He kept aloof from public life, but was the friend and trusted adviser of some of its brightest ornaments; and few have contributed more, though in a private station, to keep alive in the hearts and in the contemplation of men, a lofty standard of public virtue. If this feeble testimony, from one not wholly unknown to him, should meet the eye of any one who loved him, may it, in so far as such things can, afford that comfort under the loss, which can be derived from the knowledge that others know and feel all its irreparableness!"

ADVERTISEMENT by THE AMERICAN EDITOR TO THE FIFTH EDITION. ↩

No work upon political economy, since the publication of Dr. Adam Smith's profound and original Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, has attracted such general attention, and received such distinguished marks of approbation from competent judges, as the "Traite D'Economie Politique," of M. Say. It was first printed in Paris in the year 1803; and, subsequently, has passed through five large editions, that have received various corrections and improvements from the author. Translations of the work have been made into the German, Spanish, Italian, and other languages; and it has been adopted as a textbook in all the universities of the continent of Europe, in which this new but essential branch of liberal education is now taught. The four former American editions of this translation have also been introduced into many of the most respectable of our own seminaries of learning.

It is unquestionably the most methodical, comprehensive and best digested treatise on the elements of political economy, that has yet been presented to the world. It exhibits a clear and systematical view of all the solid and important doctrines of this very extensive and difficult science, unfolded in their proper order and connexion. In the establishment of his principles, the author's reasonings, with but few exceptions, are logical and accurate, delivered with distinctness and perspicuity, and generally supported by the fullest and most satisfactory illustrations. A rigid adherence to the inductive method of investigation, in the prosecution of almost every part of his inquiry, has enabled M. Say to effect a nearly complete analysis of the numerous and complicated phenomena of wealth, and to enunciate and establish, with all the evidence of demonstration, the simple and general laws on which its production, distribution, and consumption depend. The few slight and inconsiderable errors into which the author has fallen, do not affect the general soundness and consistency of his text, although, it is true, they are blemishes that thus far darken and disfigure it. But these are of rare occurrence, and the false conclusions involved in them may be easily detected and refuted by recurrence to the fundamental principles of the work, with which they manifestly are at variance, and contradict.

The foundation of the science of political economy was firmly laid, and the only successful method of conducting our inquiries in it pointed out and exemplified by the illustrious author of the Wealth of Nations; a number of its leading doctrines were also developed and explained by other eminent writers on the continent of Europe, who, about the same time, were engaged in investigating the nature and causes of social riches. But neither the scientific genius and penetrating sagacity of the former, nor the profound acuteness and extensive research of many of the latter, enabled them to obtain a complete discovery of all the actual phenomena of wealth, and thus to effect an entire solution of the most abstruse and difficult problems in political economy; those, namely, which demonstrate the true theory of value, and unfold the real sources of production. Aided, however, by the valuable materials collected and arranged by the labours of his distinguished predecessors, here referred to, and proceeding in the same path, our author, with the closeness and minutenes of attention due to this important study, has succeeded in examining under all their aspects, the general facts which the groundwork of the science presents, and by rejecting and excluding the accidental circumstances connected with them, has thus established its ultimate laws or principles.

Accordingly, by pursuing the inductive method of investigation, M. Say, in the most strict and philosophical manner, has deduced the true nature of value, traced up its origin, and presented a clear and accurate explanation of its theory. His definition of wealth, therefore, is more precise and correct than that of any of his predecessors in this inquiry. The agency of human industry, which Dr. Adam Smith, not with the strictest propriety, denominated labour, the important operation of natural powers, especially land, and the functions of capital, as well as the relative services of these three instruments, and the modes in which they all concur in the business of production, were first distinctly and fully pointed out and illustrated by our author. In this way he successfully unfolded the manner in which production is carried on, and imparts value to the products of agriculture, manufactures, and commerce. By, also, distinguishing reproductive from unproductive consumption, M. Say has exhibited the exact nature of capital, and its consequent important agency in production, and thus has shown why economy is a source of national wealth. Such are this author's peculiar and original speculations, the fruits of deep and patient meditation on the phenomena observed. The elementary principles derived from them, with others previously ascertained, he has combined into one harmonious, consistent, and beautiful system.

But a few of these solid and well-established positions have been criticised and objected to as inconclusive and inadmissible, by Mr. Ricardo and by Mr. Malthus, two of the ablest and most distinguished political economists among our author's contemporaries. Other doctrines in relation to the nature and origin of value have been advanced by them, and with so much plausibility too, that some of the most acute reasoners of the present day have not been sufficiently on their guard against the fallacies involved in them. The mathematical cast given to their reasonings by these writers, has captivated and led astray the understandings of intelligent and sagacious readers, and induced them to adopt, as scientific truths, what, when properly investigated and analyzed, are found to be merely specious hypotheses. Hence it is that a theory of value, purely gratuitous, has been extolled in one of the principal literary journals of Great Britain, as being "no less logical and conclusive than it was profound and important." Our author, accordingly, deemed it necessary to examine the arguments brought forward in support of these views of his opponents, in order to test their soundness and accuracy, and to submit his own principles to a further review, that he might become satisfied that the conclusions he had deduced from them had not been in any manner invalidated.

In the notes appended by M. Say to the French translation of Mr. Ricardo's Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, the reader will find what the editor deems a masterly and conclusive refutation of the theoretical errors of this author. M. Say's strictures upon the twentieth chapter of the work, entitled, "Value and Riches, their Distinctive Properties," are in his opinion decisive and unanswerable. The fallacies contained in Mr. Ricardo's theory of value, which, the editor thinks, may be traced to an anxiety to give consistency to the loose and inaccurate proposition of Dr. Adam Smith, that exchangeable value is entirely derived from human labour, are there fully exposed, and his whole train of reasoning, in connection with it, shown to rest upon an unwarrantable assumption. It must, however, be conceded that Mr. Ricardo was an intrepid and uncompromising reasoner, who always proceeded in the most direct and fearless manner from his premises to the conclusion. But not uniting with the strongest powers of reasoning, a capacity for analytical subtilty, he sometimes did not perceive verbal ambiguities in the formation of his premises, and transitions in the signification of his terms in the conduct of his argument, which, in these instances, vitiated his conclusions. The fundamental errors into which he has fallen, accordingly, do not arise from any want of strictness in his deductions, but from undue generalizations and perversions of language. In M. Say's Letters to Mr. Malthus, which have been translated by Mr. Richter, the points at issue between these two eminent political economists are discussed in the most luminous, impartial, and satisfactory manner; and by all candid and unprejudiced critics must be considered as bringing the controversy to a close.

It is not his intention, nor would it be proper on this occasion, for the editor to enter further into the merits of the controversial writings of our author. Any dispassionate inquirer, who will take the pains carefully to review the whole ground in dispute, will, he thinks, find that the disquisitions referred to contain a triumphant vindication of such of the author's general principles as had been assailed by his ingenious opponents. Whenever the study of the science of political economy shall be more generally cultivated as an essential branch of early education, most of the abstruse questions involved in the controversies which now divide the writers on this subject will be brought to a conclusion; the accession of useful knowledge it will occasion will more effectually eradicate the prejudices which have given birth to these disputes and misconceptions, than any direct argumentative refutation.

The great merits of this treatise on political economy are now beginning to be well known and properly estimated by that class of readers who take a deep interest in the progress of a science, which "aims at the improvement of society," as Dugald Stewart so truly remarks, "not by delineating plans of new constitutions, but by enlightening the policy of actual legislators;" a science, therefore, with the right understanding of whose principles, the welfare and happiness of mankind are intimately connected.

In alluding to this admirable work of M. Say, Mr. Ricardo remarks, "that its author not only was the first, or among the first, of continental writers, who justly appreciated and applied the principles of Smith, and who has done more than all other continental writers taken together, to recommend the principles of that enlightened and beneficial system to the nations of Europe; but who has succeeded in placing the science in a more logical, and more instructive order; and has enriched it by several discussions, original, accurate, and profound."

The English public has for some time been in possession of the present excellent translation of this treatise by Mr. Prinsep; the first edition of which was published in London in the spring of 1821. It is executed with spirit, elegance, and general fidelity, and is a performance, in every respect, worthy of the original. It is here given to the American reader without any material alteration.

In various notes which the English translator has thought proper to subjoin to his edition of the text, he has wasted much ingenuity in endeavouring to overthrow some of the author's leading principles, which, notwithstanding these attacks, are as fixed and immutable as the truths which constitute their basis. Had Mr. Prinsep more thoroughly studied M. Say's profound theoretical views on the subject of value, and had he, also, made himself acquainted, which it nowhere appears that he has done, with the powerful and victorious defence of these doctrines, contained in the notes on Mr. Ricardo's work, and in the letters to Mr. Malthus, already referred to, he perhaps might have discovered, that they are the ultimate generalizations of facts, which, agreeably to the most legitimate rules of philosophizing, the author was entitled to lay down as general laws or principles. At all events, Mr. Prinsep should not have ventured upon an attack on these first principles of the science of political economy, without this previous examination.

Such, therefore, of these notes of the English translator as are in opposition to the well-established elements of the science, and have no other support than the hypothesis of Mr. Ricardo and Mr. Malthus, have been entirely omitted; the American editor not deeming himself under any obligation to give currency to errors, which would perpetually interrupt and distract the attention of the reader in a most abstruse and difficult inquiry. Other notes of the translator, which contain interesting and valuable illustrations of other general principles of the work, drawn from the actual state of Great Britain and her colonies, have been retained in this edition, as appropriate and useful. The translator's remarks on the pernicious character and tendency of the restrictive and prohibitive policy, are particularly worthy of regard, confirming as they most fully do, on this subject, all the important conclusions of the author. The folly of attempting, either by extraordinary encouragements, to attract towards some branches of production a larger share of capital and industry than would be naturally employed in them, or by uncommon restraints forcibly to divert from others a portion of the capital and industry that would otherwise be invested in them, is at last beginning to be understood.

The restrictive system, or that which by means of legislative enactments endeavours to give a particular direction to national capital and industry, derived its whole support from the assumption of positions now generally admitted to be gratuitous and unfounded, namely, that in trade whatever is gained by one nation must necessarily be lost by another, that wealth consists exclusively of the precious metals, and consequently, that in all sales of commodities, the great object should be to obtain returns in gold and silver. In Europe these erroneous opinions have now, for some time, been relinquished by political economists of all the various schools, some of whom yet differ and dispute respecting a few of the more recondite and ultimate elements of the science. In the whole range of inquiry in political economy, perhaps there is not a single proposition better established, or one that has obtained a more universal sanction from its enlightened cultivators in every country, than the liberal doctrine, that the most active, general, and profitable employments are given to the industry and capital of every people, by allowing to their direction and application the most perfect freedom, compatible with the security of property. This fundamental position of political economy, and the various principles that flow from it as corollaries, were first systematically developed, explained, and taught by the great father of the science, Dr. Adam Smith; although glimpses of the same important truth had previously, and about the same time, reached the minds of a few eminent individuals in other parts of the world. "The most effectual plan for advancing a people to greatness," says Dr. Smith, "is to maintain that order of things which nature pointed out; by allowing every man, as long as he observes the rules of justice, to pursue his own interest in his own way, and to bring both his industry and his capital into the freest competition with those of his fellow-citizens." Animated by a like desire to promote the improvement and happiness of mankind, with that which actuated the author of the Wealth of Nations, the most profound inquiries among his successors embraced his enlarged and benevolent views, as the only certain means of increasing the general prosperity, and eloquently maintained and enforced them. The doctrines of the freedom of trade and the rights of industry, were vindicated and taught by all the distinguished British political economists; namely, by Dugald Stewart, Ricardo, Malthus, Torrens, Horner, Huskisson, Lauderdale, Bentham, Mills, Craig, Lowe, Tooke, Senior, Bowring, M'Culloch, and Whatley; and, on the continent of Europe, by authors as celebrated, by Say, Droz, Sismondi, Storch, Garnier, Destutt-Tracy, Ganilh, Jovellanos, Sartorius, Queypo, Leider, Von Schlozer, Kraus, Weber, Muller, Scarbeck, Pechio, and Gioja.

"Under a system of perfectly free commerce," says Mr. Ricardo, "each country naturally devotes its capital and labour to such employments as are most beneficial to each. This pursuit of individual advantage is admirably connected with the universal good of the whole. By stimulating industry, by rewarding ingenuity, and by using most efficaciously the powers bestowed by nature, it distributes labour most effectively and most economically: while by increasing the general mass of productions, it diffuses general benefit, and binds together by one common tie of interest and intercourse, the universal society of nations throughout the civilized world. It is this principle which determines that wine shall be made in France and Portugal, that corn shall be grown in America and Poland, and that hardware and other goods shall be manufactured in England."

Our own celebrated countryman, Franklin, too, with a sagacity and force which always characterized his intellect, maintained and exemplified in his "Essay on the Principles of Trade," what he therein repeatedly called "the great principle of freedom in trade." Even before the appearance of the Wealth of Nations, he had with almost intuition anticipated some of the most profound conclusions of the science of political economy, which other inquirers had arrived at only after a patient and laborious analysis of its phenomena. The new and generous commercial policy is not more beholden for support and currency to the arguments and illustrations of any of its early expositors, than to the clear and vigorous pen of the highly gifted American philosopher. "The expressions, Laissez nous faire, and pas trop gouverner," which, to use the language of Dugald Stewart, the highest of all authorities, "comprise in a few words two of the most important lessons of political wisdom, are indebted chiefly for their extensive circulation, to the short and luminous comments of Franklin, which had so extraordinary an influence on public opinion, both in the Old and New World." Nevertheless, strange as it may seem, by a perversion or misconception of a few of his incidental opinions, the name of the first of practical statesmen has been invoked, and its authority employed among us, in aid of a system of restraints and prohibitions on commerce, which it was the chief aim of his politico-economical writings to refute and condemn, as alike repugnant to sound theory and destructive to national prosperity. Whenever American statesmen and legislators shall have as clear and steady perceptions as Franklin of the truth and wisdom of the doctrine of commercial freedom, we may expect that our national and state codes will no longer exhibit so many traces of that empirical spirit of tampering regulation which, instead of invigorating and quickening the development of national wealth, only cramps and retards its natural growth. "Where should we expect," says M. Say, in a letter to the editor, "sound doctrine to be better received than amongst a nation that supports and illustrates the value of free principles, by the most striking examples. The old states of Europe are cankered with prejudices and bad habits; it is America who will teach them the height of prosperity which may be reached when governments follow the counsels of reason, and do not cost too much."

The preliminary discourse has been translated by the American editor, and in his editions of the work restored to its place. The editor must confess that he is at a loss to account for the omission by the English translator of so material a part of the author's treatise as this introduction to his whole inquiry. In itself it is a performance of uncommon merit, has immediate reference to, and sheds much light over, the general views unfolded in the body of the work. The nature and object of the science of political economy, the only certain method of conducting any of our inquiries in it with success, and the causes which have hitherto so much retarded its advancement, are all considered and pointed out with great clearness and ability. The author has also connected with it a highly interesting and instructive historical sketch of the progress of this science during the last and present century, interspersed with numerous judicious and acute criticisms upon the writings and opinions of his predecessors. Moreover, this discourse, throughout every part, is deeply philosophical, and well calculated to prepare the reader for the study on which he is about to enter. The editor has, therefore, he trusts, performed an acceptable service in putting the American student in possession of so important a part of the original work.1

Notes have also been subjoined by the American editor, for the purpose of marking a few inconsiderable errors and inconsistencies into which the author has inadvertently fallen, and of supplying an occasional illustration, drawn from other authors, of such passages of the text as seemed to require further elucidation or correction.

Introduction

A SCIENCE only advances with certainty, when the plan of inquiry and the object of our researches have been clearly defined; otherwise a small number of truths are loosely laid hold of, without their connexion being perceived, and numerous errors, without being enabled to detect their fallacy.

For a long time the science of politics, in strictness limited to the investigation of the principles which lay the foundation of the social order, was confounded with political economy, which unfolds the manner in which wealth is produced, distributed, and consumed. Wealth, nevertheless, is essentially independent of political organization. Under every form of government, a state, whose affairs are well administered, may prosper. Nations have risen to opulence under absolute monarchs, and have been ruined by popular councils. If political liberty is more favourable to the development of wealth, it is indirectly, in the same manner that it is more favourable to general education.

In confounding in the same researches the essential elements of good government with the principles on which the growth of wealth, either public or private, depends, it is by no means surprising that authors should have involved these subjects in obscurity, instead of elucidating them. Stewart, who has entitled his first chapter "Of the Government of Mankind," is liable to this reproach; the sect of "Economists" of the last century, throughout all their writings, and J. J. Rousseau, in the article "Political Economy" in the Encyclopedie, lie under the same imputation.

Since the time of Adam Smith, it appears to me, these two very distinct inquiries have been uniformly separated, the term political economy2 being now confined to the science which treats of wealth, and that of politics, to designate the relations existing between a government and its people, and the relations of different states to each other.

The wide range taken into the field of pure politics, whilst investigating the subject of political economy, seemed to furnish a much stronger reason for including in the same inquiry agriculture, commerce and the arts, the true sources of wealth, and upon which laws have but an accidental and indirect influence. Thence what interminable digressions! If, for example, commerce constitutes a branch of political economy, all the various kinds of commerce form a part; and as a consequence, maritime commerce, navigation, geography—where shall we stop? All human knowledge is connected. Accordingly, it is necessary to ascertain the points of contact, or the articulations by which the different branches are united; by this means, a more exact knowledge will be obtained of whatever is peculiar to each, and where they run into one another.

In the science of political economy, agriculture, commerce and manufactures are considered only in relation to the increase or diminution of wealth, and not in reference to their processes of execution. This science indicates the cases in which commerce is truly productive, where whatever is gained by one is lost by another, and where it is profitable to all; it also teaches us to appreciate its several processes, but simply in their results, at which it stops. Besides this knowledge, the merchant must also understand the processes of his art. He must be acquainted with the commodities in which he deals, their qualities and defects, the countries from which they are derived, their markets, the means of their transportation, the values to be given for them in exchange, and the method of keeping accounts.

The same remark is applicable to the agriculturist, to the manufacturer, and to the practical man of business; to acquire a thorough knowledge of the causes and consequences of each phenomenon, the study of political economy is essentially necessary to them all; and to become expert in his particular pursuit, each one must add thereto a knowledge of its processes. These different subjects of investigation were not, however, confounded by Dr. Smith; but neither he, nor the writers who succeeded him, have guarded themselves against another source of confusion, here important to be noticed, inasmuch as the developments resulting from it, may not be altogether unuseful in the progress of knowledge in general, as well as in the prosecution of our own particular inquiry.

In political economy, as in natural philosophy, and in every other study, systems have been formed before facts have been established; the place of the latter being supplied by purely gratuitous assertions. More recently, the inductive method of philosophizing, which, since the time of Bacon, has so much contributed to the advancement of every other science, has been applied to the conduct of our researches in this. The excellence of this method consists in only admitting facts carefully observed, and the consequences rigorously deduced from them; thereby effectually excluding those prejudices and authorities which, in every department of literature and science, have so often been interposed between man and truth. But, is the whole extent of the meaning of the term, facts, so often made use of, perfectly understood?

It appears to me, that this word at once designates objects that exist, and events that take place; thus presenting two classes of facts: it is, for example, one fact, that such an object exists; another fact, that such an event takes place in such a manner. Objects that exist, in order to serve as the basis of certain reasoning, must be seen exactly as they are, under every point of view, with all their qualities. Otherwise, whilst supposing ourselves to be reasoning respecting the same thing, we may, under the same name, be treating of two different things.

The second class of facts, namely, events that take place, consists of the phenomena exhibited, when we observe the manner in which things take place. It is, for instance, a fact, that metals, when exposed to a certain degree of heat, become fluid.

The manner in which things exist and take place, constitutes what is called the nature of things; and a careful observation of the nature of things is the sole foundation of all truth.

Hence, a twofold classification of sciences; namely, those which may be styled descriptive, which arrange and accurately designate the properties of certain objects, as botany and natural history; and those which may be styled experimental, which unfold the reciprocal action of substances on each other, or in other words, the connexion between cause and effect, as chemistry and natural philosophy. Both departments are founded on facts, and constitute an equally solid and useful portion of knowledge. Political economy belongs to the latter; in showing the manner in which events take place in relation to wealth, it forms a part of experimental science.3

But facts that take place may be considered in two points of view; either as general or constant, or as particular or variable. General facts are the results of the nature of things in all analogous cases; particular facts as truly result from the nature of things, but they are the result of several operations modified by each other in a particular case. The former are not less incontrovertible than the latter, even when apparently they contradict each other. In natural philosophy, it is a general fact, that heavy bodies fall to the earth; the water in a fountain, nevertheless, rises above it. The particular fact of the fountain is a result wherein the laws of equilibrium are combined with those of gravity, but without destroying them.

In our present inquiry, the knowledge of these two classes of facts, namely, of objects that exist and of events that take place, embraces two distinct sciences, political economy and statistics.

Political economy, from facts always carefully observed, makes known to us the nature of wealth; from the knowledge of its nature deduces the means of its creation, unfolds the order of its distribution, and the phenomena at tending its destruction. It is, in other words, an exposition of the general facts observed in relation to this subject. With respect to wealth, it is a knowledge of effects and of their causes. It shows what facts are constantly conjoined with; so that one is always the sequence of the other. But it does not resort for any further explanations to hypothesis: from the nature of particular events their concatenations must be perceived; the science must conduct us from one link to another, so that every intelligent understanding may clearly comprehend in what manner the chain is united. It is this which constitutes the excellence of the modern method of philosophizing.

Statistics exhibit the amount of production and of consumption of a particular country, at a designated period; its population, military force, wealth, and whatever else is susceptible of valuation. It is a description in detail.

Between political economy and statistics there is the same difference as between the science of politics and history.

The study of statistics may gratify curiosity, but it can never be productive of advantage when it does not indicate the origin and consequences of the facts it has collected; and by indicating their origin and consequences, it at once becomes the science of political economy. This doubtless is the reason why these two distinct sciences have hitherto been confounded. The celebrated work of Dr. Adam Smith can only be considered as an immethodical assemblage of the soundest principles of political economy, supported by luminous illustrations; of highly ingenious researches in statistics, blended with instructive reflections; it is not, however, a complete treatise of either science, but an irregular mass of curious and original speculations, and of known demonstrated truths.

A perfect knowledge of the principles of political economy may be obtained, inasmuch as all the general facts which compose this science may be discovered. In statistics this never can be the case; this latter science, like history, being a recital of facts, more or less uncertain, and necessarily incomplete. Of the statistics of former periods and distant countries, only detached and very imperfect accounts can be furnished. With respect to the present time, there are few persons who unite the qualifications of good observers with a situation favourable for accurate observation. The inaccuracy of the statements we are compelled to have recourse to, the restless suspicions of particular governments, and even of individuals, their ill-will and indifference, present obstacles often in surmountable, notwithstanding the toil and care of inquirers to collect minute details with exactness; and which after all, when in their possession, are only true for an instant. Dr. Smith accordingly avows, that he puts no great faith in political arithmetic; which is nothing more than the arrangement of numerous statistical data.

Political economy, on the other hand, whenever the principles which constitute its basis are the rigorous deductions of undeniable general facts, rests upon an immoveable foundation. General facts undoubtedly are founded upon the observation of particular facts; but upon such particular facts as have been selected from those most carefully observed, best established, and witnessed by ourselves. When the results of these facts have uniformly been the same, the cause of their having been so satisfactorily demonstrated, and the exceptions to them even confirming other principles equally well established, we are authorised to give them as ultimate general facts, and to submit them with confidence to the examination of all competent inquirers, who may be again desirous of subjecting them to experiment. A new particular fact, when insulated, and the connexion between its antecedents and consequents not established by reasoning, is not sufficient to shake our confidence in a general fact; for who can say that some unknown circumstance has not produced the difference noticed in their several results? A light feather is seen to mount in the air, and sometimes remain there for a long time before it falls back to the ground. Would it not, nevertheless, be erroneous to conclude that this feather is not affected by the universal law of gravitation? In political economy it is a general fact, that the interest of money rises in proportion to the risk run by the lender of not being repaid. Shall it be inferred that this principle is false, from having seen money lent at a low rate of interest upon hazardous occasions? The lender may have been ignorant of the risk, gratitude or fear may have induced sacrifices, and the general law, disturbed in this particular case, will resume its entire force the moment the causes of its interruption have ceased to operate. Finally, how small a number of particular facts are completely examined, and how few among them are observed under all their aspects? And in supposing them well examined, well observed, and well described, how many of them either prove nothing, or directly the reverse of what is intended to be established by them.

Hence, there is not an absurd theory, or an extravagant opinion that has not been supported by an appeal to facts;4 and it is by facts also that public authorities have been so often misled. But a knowledge of facts, without a knowledge of their mutual relations, without being able to show why the one is a cause, and the other a consequence, is really no better than the crude information of an office-clerk, of whom the most intelligent seldom becomes acquainted with more than one particular series, which only enables him to examine a question in a single point of view.

Nothing can be more idle than the opposition of theory to practice! What is theory, if it be not a knowledge of the laws which connect effects with their causes, or facts with facts? And who can be better acquainted with facts than the theorist who surveys them under all their aspects, and comprehends their relation to each other? And what is practice5 without theory, but the employment of means without knowing how or why they act? In any investigation, to treat dissimilar cases as if they were analogous, is but a dangerous kind of empiricism, leading to conclusions never foreseen.

Hence it is, that after having seen the exclusive or restrictive system of commerce, a system founded on the opinion that one nation can only gain what another loses, almost universally adopted throughout Europe after the revival of arts and letters; after having seen taxation without intermission perpetually increasing, and in some countries extending itself to a most enormous amount; and after having seen these same countries become more opulent, more populous, and more powerful, than at the time they carried on an unrestricted trade, and were almost entirely exempt from public burdens, the generality of mankind have concluded that national wealth and power were attributable to the restraints imposed on the application of industry, and to the taxes levied from the incomes of individuals. Shallow thinkers have even pretended that this opinion was founded on facts, and that every different one was the offspring of a wild and disordered imagination.

It is, however, on the contrary, evident that the supporters of the opposite opinion embraced a wider circle of facts, and understood them much better than their opponents. The very remarkable impulse given, during the middle ages, to the industry of the free states of Italy and of the Hanse towns of the north of Europe, the spectacle of riches it exhibited in both, the shock of opinions occasioned by the crusades, the progress of the arts and sciences, the improvement of navigation and consequent discovery of the route to India, and of the continent of America, as well as a succession of other less important events, were all known to them as the true causes of the increased opulence of the most ingenious nations on the globe. And although they were aware that this activity had received successive checks, they at the same time knew that it had been freed from more oppressive obstacles. In consequence of the authority of the feudal lords and barons declining, the intercourse between the different provinces and states could no longer be interrupted; roads became improved, travelling more secure, and laws less arbitrary; the enfranchised towns, becoming immediately dependent upon the crown, found the sovereign interested in their advancement; and this enfranchisement, which the natural course of things and the progress of civilization had extended to the country, secured to every class of producers the fruits of their industry. In every part of Europe personal freedom became more generally respected; if not from a more improved organization of political society, at least from the influence of public sentiment. Certain prejudices, such as branding with the odious name of usury all loans upon interest, and attaching the importance of nobility to idleness, had begun to decline. Nor is this all. Enlightened individuals have not only remarked the influence of these, but of many other analogous facts; it has been perceived by them, that the decline of prejudices has been favourable to the advancement of science, or to a more exact knowledge of the immutable laws of nature; that this improvement in the cultivation of science has itself been favourable to the progress of industry, and industry to national opulence. From such an induction of facts they have been enabled to conclude, with much greater certainty than the unthinking multitude, that although many modern states in the midst of taxation and restrictions have risen to opulence and power, it is not owing to these restraints on the natural course of human affairs, but in spite of such powerful causes of discouragement. The prosperity of the same countries would have been much greater, had they been governed by a more liberal and enlightened policy.6

To obtain a knowledge of the truth, it is not then so necessary to be acquainted with a great number of facts, as with such as are essential, and have a direct and immediate influence; and, above all, to examine them under all their aspects, to be enabled to deduce from them just conclusions, and be assured that the consequences ascribed to them do not in reality proceed from other causes. Every other knowledge of facts, like the erudition of an almanac, is a mere compilation from which nothing results. And it may be remarked, that this sort of information is peculiar to men of clear memories and clouded judgments; men who declaim against the best established doctrines, the fruits of the most enlarged experience and profoundest reasoning; and whilst inveighing against system, whenever their own routine is departed from, are precisely those most under its influence, and who defend it with stubborn folly, fearful rather of being convinced, than desirous of arriving at certainty.

Thus, if from all the phenomena of production, as well as from the experience of the most extensive commerce, you demonstrate that a free intercourse between nations is reciprocally advantageous, and that the mode found to be most beneficial to individuals transacting business with foreigners, must be equally so to nations, men of contracted views and high presumption will accuse you of system. Ask them for their reasons, and they will immediately talk to you of the balance of trade; will tell you, it is clear that a nation must be ruined by exchanging its money for merchandise—in itself a system. Some will assert that circulation enriches a state, and that a sum of money, by passing through twenty different hands, is equivalent to twenty times its own value; others, that luxury is favourable to industry, and economy ruinous to every branch of commerce—both mere systems; and all will appeal to facts in support of these opinions, like the shepherd, who, upon the faith of his eyes, affirmed that the sun, which he saw rise in the morning and set in the evening, during the day traversed the whole extent of the heavens, treating as an idle dream the laws of the planetary world.

Persons, moreover, distinguished by their attainments in other branches of knowledge, but ignorant of the principles of this, are too apt to suppose that absolute truth is confined to the mathematics and to the results of careful observation and experiment in the physical sciences; imagining that the moral and political sciences contain no invariable facts or indisputable truths, and therefore cannot be considered as genuine sciences, but merely hypothetical systems, more or less ingenious, but purely arbitrary. The opinion of this class of philosophers is founded upon the want of agreement among the writers who have investigated these subjects, and from the wild absurdities taught by some of them. But what science has been free from extravagant hypotheses? How many years have elapsed since those most advanced have been altogether disengaged from system? On the contrary, do we not still see men of perverted understandings attacking the best established positions? Forty years have not elapsed since water, so essential to our very existence, and the atmosphere in which we perpetually breathe, have been accurately analyzed. The experiments and demonstrations, nevertheless, upon which this doctrine is founded, are continually assailed; although repeated a thousand times in different countries by the most acute and cautious experimenters. A want of agreement exists in relation to a description of facts much more simple and obvious than the most part of those in moral and political science. Are not natural philosophy, chemistry, botany, mineralogy, and physiology, still fields of controversy, in which opinions are combated with as much violence and asperity as in political economy? The same facts are, indeed, observed by both parties, but are classed and explained differently by each; and it is worthy of remark, that in these contests genuine philosophers are not arrayed against pretenders. Leibnitz and Newton, Linnæus and Jussieu, Priestley and Lavoisier, Desaussure and Dolomieu, were all men of uncommon genius, who, however, did not agree in their philosophical systems. But have not the sciences they taught an existence, notwithstanding these disagreements?7

In like manner, the general facts constituting the sciences of politics and morals, exist independently of all controversy. Hence the advantage enjoyed by every one who, from distinct and accurate observation, can establish the existence of these general facts, demonstrate their connexion, and deduce their consequences. They as certainly proceed from the nature of things as the laws of the material world. We do not imagine them; they are results disclosed to us by judicious observation and analysis. Sovereigns, as well as their subjects, must bow to their authority, and never can violate them with impunity.

General facts, or, if you please, the general laws which facts follow, are styled principles, whenever it relates to their application; that is to say, the moment we avail ourselves of them in order to ascertain the rule of action of any combination of circumstances presented to us. A knowledge of principles furnishes the only certain means of uniformly conducting any inquiry with success.

Political economy, in the same manner as the exact sciences, is composed of a few fundamental principles, and of a great number of corollaries or conclusions, drawn from these principles. It is essential, therefore, for the advancement of this science that these principles should be strictly deduced from observation; the number of conclusions to be drawn from them may afterwards be either multiplied or diminished at the discretion of the inquirer, according to the object he proposes. To enumerate all their consequences, and give their proper explanations, would be a work of stupendous magnitude, and necessarily incomplete. Besides, the more this science shall become improved, and its influence extended, the less occasion will there be to deduce consequences from its principles, as these will spontaneously present themselves to every eye; and being within the reach of all, their application will be readily made. A treatise on political economy will then be confined to the enunciation of a few general principles, not requiring even the support of proofs or illustrations; because these will be but the expression of what every one will know, arranged in a form convenient for comprehending them, as well in their whole scope as in their relation to each other.

It would, however, be idle to imagine that greater precision, or a more steady direction could be given to this study, by the application of mathematics to the solution of its problems. The values with which political economy is concerned, admitting of the application to them of the terms plus and minus, are indeed within the range of mathematical inquiry; but being at the same time subject to the influence of the faculties, the wants and the desires of mankind, they are not susceptible of any rigorous appreciation, and cannot, therefore, furnish any data for absolute calculations. In political as well as in physical science, all that is essential is a knowledge of the connexion between causes and their consequences. Neither the phenomena of the moral or material world are subject to strict arithmetical computation.8

These considerations respecting the nature and object of political economy, and the best method of obtaining a thorough knowledge of its principles, will supply us with the means of appreciating the efforts hitherto made towards the advancement of this science.

The literature of the ancients, their legislation, their public treaties, and their administration of the conquered provinces, all proclaim their utter ignorance of the nature and origin of wealth, of the manner in which it is distributed, and of the effects of its consumption. They knew, what has always been known wherever the right of property has been sanctioned by laws, that riches are increased by economy, and diminished by extravagance. Xenophon extols order, activity, and intelligence, as certain means of obtaining prosperity; but without deducing these maxims from any general law, or without being able to show the connexion between causes and their consequences. He advises the Athenians to protect commerce, and to receive strangers with kindness; yet so little was he aware to what extent this advice would be proper, that, upon another occasion, he expresses doubts whether commerce be really profitable to the republic.

Plato and Aristotle, it is true, notice some invariable relations between the different modes of production, and the results obtained from them. Plato sketches with tolerable fidelity,9 the effects of the separation of social employments; but it is simply with a view to illustrate man's social character and the necessity he is in, from his multifarious wants, of uniting in extensive societies in which each individual may be exclusively occupied with one species of production. His view is entirely a political one; and he has deduced from it no other conclusion.

In his treatise on Politics, Aristotle goes farther. He distinguishes natural from artificial production. He styles natural, whatever creates those objects of consumption required by a family, or, at most, whatever is obtained by exchanges in kind. No other advantage, according to him, is derived from real production; artificial gain he condemns. Besides, he does not support these opinions by any reasoning founded upon accurate observation. From the manner in which he expresses himself in relation to the effect of savings and loans on interest, it is evident that he knew nothing of the nature and employment of capital.

What can we expect from nations still less advanced in civilization than the Greeks? We may recollect that a law of Egypt obliged the son to adopt the profession of his father. This, in certain cases, was to require the creation of a greater quantity of products than the particular state of society called for; to oblige an individual, in order to obey the law, to ruin himself, and to continue the exercise of his productive functions, whether in possession of capital or not; which is altogether absurd.10 The Romans, in treating every branch of industry, except agriculture (and we know not why,) with contempt, betray the same ignorance. Their pecuniary transactions must be numbered amongst their most unskillful operations.

The moderns, even after having freed themselves from the barbarism of the middle ages, have not for a very long time been more advanced. We shall have occasion to notice the stupidity of a multitude of laws relating to the Jews, to the interest of money, and to money itself. Henry IV. granted to his favourites and mistresses, as favours which cost him nothing, the permission to practise a thousand petty extortions, and to collect for their own benefit, from various branches of commerce, as many petty taxes. He authorized the count of Soissons to levy a duty of fifteen sous upon every bale of merchandise which should be exported from the kingdom.11

In every branch of knowledge, example has preceded precept. The fortunate enterprises of the Portuguese and Spaniards during the fifteenth century, the active industry of Venice, Genoa, Florence, Pisa, the provinces of Flanders, and the free cities of Germany at this same epoch, gradually directed the attention of some philosophers to the theory of wealth.

These inquiries, like almost every other in the arts and sciences, after the revival of letters, originated in Italy. As far back as the sixteenth century, Botero was engaged in investigating the real sources of public prosperity. In the year 1613, Antonio Serra composed a treatise, in which he particularly noticed the productive power of industry; but the title of his work sufficiently indicates its errors. Wealth, according to his hypothesis, consisted only of gold and silver.12 Davanzati wrote upon money and upon exchange; and at the beginning of the eighteenth century, fifty years before the time of Quesnay, Bandini of Sienna had shown, both from reasoning and experience, that there never had been a scarcity of food, except in those countries where the government had itself interfered to supply the people. Belloni, a banker at Rome, in the year 1750, published a dissertation on commerce, evincing his intimate acquaintance with the nature of money and exchanges, although at the same time infected with the theory of the balance of trade. His labours were rewarded by the Pope with the title of marquess. Carli, before Dr. Smith, demonstrated that the balance of trade neither taught nor proved any thing. Algarotti, whose writings on other subjects Voltaire has made known, wrote also upon the science of political economy; and the little he has left exhibits the accuracy and extent of his knowledge, as well as his acuteness. He confines himself so strictly to facts, and so uniformly founds his speculations on the nature of things, that although he did not get possession of the proof of his principles, and of their relation to each other, he has, nevertheless, guarded himself against every thing like hypothesis and system. In 1764, Genovesi commenced a course of public lectures on political economy, in the chair founded at Naples by the care of the highly esteemed and learned Intieri. In consequence of this example, other professorships of political economy were afterwards established at Milan, and more recently in most of the universities in Germany and Russia.

In 1750, the abbé Galiani, so well known since from his connexion with many of the French philosophers, and by his Dialogues on the Corn Trade, although at that time a very young man, published a Treatise on Money, which discovered such uncommon talents and information, as to induce a belief that he had been assisted in the composition of his work by the abbé Intieri and the Marquess of Rinuccini. Its merits, however, appear to be of a description similar to those the author's writings always afterwards displayed; genius united with erudition, carefulness in uniformly ascending to the nature of things; and an animated and elegant style.

One of the most striking peculiarities of this work, is its containing some of the rudiments of the doctrine of Adam Smith; among others, that labour is the sole creator of the value of things or of wealth;13 a principle although not rigorously true, as will be made manifest in the course of this work, but which, pushed to its ultimate consequences, would have put Galiani in the way of discovering and completely unfolding the phenomena of production. Dr. Smith, who was about the same time a professor in the university of Glasgow, and then taught this doctrine, which has since acquired so much celebrity, in all probability had no knowledge of a work in the Italian language, published at Naples by a young man then hardly known, and whom he has never quoted. But even had he known it, a truth cannot with so much propriety be said to belong to its fortunate discoverer, as to the inquirer who first proves that it must be so, and demonstrates its consequences. Although the existence of universal gravitation had been previously conjectured by Kepler and Pascal, the discovery does not the less belong to Newton.14

In Spain, Alvarez Osorio, and Martinez-de-mata, have delivered discourses on political economy, the publication of which we owe to the enlightened patriotism of Campomanes. Moncada, Navarette, Ustaritz, Ward, and Ulloa, have written on the same subject. These esteemed authors, like those of Italy, entertained many sound views, verified various important facts, and supplied a number of laborious calculations; but from their inability to establish them upon fundamental principles of the science, which were not then known, they have often been mistaken both as to the end as well as the means of prosecuting this study; amidst a variety of useless disquisitions, have only cast an uncertain and deceptive light.15

In France, the science of political economy, at first, was only considered in its application to public finances. Sully remarks correctly enough, that agriculture and commerce are the two teats of the state; but from a vague and indistinct conception of the truth. The same observation may be applied to Vauban, a man of a sound practical mind, and although in the army, a philosopher and friend of peace, who, deeply afflicted with the misery into which his country had been plunged by the vain-glory of Louis XIV., proposed a more equitable assessment of the taxes, as a means of alleviating the public burdens.

Under the influence of the regent, opinions became unsettled; bank-notes, supposed to be an inexhaustible source of wealth, were only the means of swallowing up capital, of expending what had never been earned, and of making a bankruptcy of all debts. Moderation and economy were turned into ridicule. The courtiers of the prince, either by persuasion or corruption, encouraged him in every species of extravagance. At this period, the maxim that a state is enriched by luxury was reduced to system. All the talents and wit of the day were exerted in gravely maintaining such a paradox in prose, or in embellishing it with the more attractive charms of poetry. The dissipation of the national treasures was really supposed to merit the public gratitude. The ignorance of first principles, with the debauchery and licentiousness of the duke of Orleans, conspired to effect the ruin of the kingdom. During the long peace maintained by cardinal Fleury, France recovered a little; the insignificant administration of this weak minister at least proving, that the ruler of a nation may achieve much good by abstaining from the commission of evil.

The steadily increasing progress of different branches of industry, the advancement of the sciences, whose influence upon wealth we shall have occasion hereafter to notice, and the direction of public opinion, at length estimating national prosperity as being of some importance, caused the science of political economy to enter into the contemplation of a great number of writers. Its true principles were not then known; but since, according to the observation of Fontenelle, our condition is such, that we are not permitted at once to arrive at the truth, but must previously pass through various species of errors and various grades of follies, ought these false steps to be considered as altogether useless, which have taught us to advance with more steadiness and certainty?

Montesquieu, who was desirous of considering laws in all their relations, inquired into their influence on national wealth. The nature and origin of wealth he should first have ascertained; of which, however, he did not form any opinion. We are, nevertheless, indebted to this distinguished author for the first philosophical examination of the principles of legislation; and, in this point of view, he, perhaps, may be considered as the master of the English writers, who are so generally esteemed as being ours; just in the same manner as Voltaire has been the master of their best historians, who now furnish us with models worthy of imitation.

About the middle of the eighteenth century, certain principles in relation to the origin of wealth, advanced by Doctor Quesnay, made a great number of proselytes. The enthusiastic admiration manifested by these persons for the founder of their doctrines, the scrupulous exactness with which they have uniformly since followed the same dogmas, and the energy and zeal they displayed in maintaining them, have caused them to be considered as a sect, which has received the name of economists. Instead of first observing the nature of things, or the manner in which they take place, of classifying these observations, and deducing from them general propositions, they commenced by laying down certain abstract general propositions, which they styled axioms, from supposing them to contain inherent evidence of their own truth. They then endeavoured to accommodate the particular facts to them, and to infer from them their laws; thus involving themselves in the defence of maxims evidently at variance with common sense and universal experience,16 as will appear hereafter in various parts of this work. Their opponents had not themselves formed any more correct views of the subjects in controversy. With considerable learning and talents on both sides, they were either wrong or right by chance. Points were contested that should have been conceded, and opinions, unquestionably false, acquiesced in; in short, they combated in the clouds. Voltaire, who so well knew how to detect the ridiculous, wherever it was to be found, in his Homme aux quarante ecus, satirised the system of the economists; yet, in exposing the tiresome trash of Mercer de la Riviere, and the absurdities contained in Mirabeau's L'ami des Hommes, he was himself unable to point out the errors of either.

The economists, by promulgating some important truths, directing a more general attention to objects of public utility, and by exciting discussions, which, although at that time of no advantage, subsequently led to more accurate investigations, have unquestionably done much good.17 In representing agricultural industry as productive of wealth, they were not deceived; and, perhaps, the necessity they were in of unfolding the nature of production, caused the further examination of this important phenomenon, which conducted their successors to its entire development. On the other hand, the labours of the economists have been attended with serious evils; the many useful maxims they decried, their sectarian spirit, the dogmatical and abstract language of the greater part of their writings, and the tone of inspiration pervading them, gave currency to the opinion, that all who were engaged in such studies were but idle dreamers, whose theories, at best only gratifying literary curiosity, were wholly inapplicable in practice.18

No one, however, has ever denied that the writings of the economists have uniformly been favourable to the strictest morality, and to the liberty which every human being ought to possess, of disposing of his person, fortune, and talents, according to the bent of his inclination; without which, indeed, individual happiness and national prosperity are but empty and unmeaning sounds. These opinions alone entitle their authors to universal gratitude and esteem. I do not, moreover, believe that a dishonest man or bad citizen can be found among their number.

This doubtless is the reason why, since the year 1760, almost all the French writers of any celebrity on subjects connected with political economy, without absolutely being enrolled under the banners of the economists, have, nevertheless, been influenced by their opinions. Raynal, Condorcet, and many others, will be found among this number. Condillac may also be enumerated among them, notwithstanding his endeavours to found a system of his own in relation to a subject which he did not understand. Many useful hints may be collected from amidst the ingenious trifling of his work;19 but, like the economists, he almost invariably founds a principle upon some gratuitous assumption. Now, an hypothesis may indeed be resorted to, in order to exemplify and elucidate the correctness of an author's general reasoning, but never can be sufficient to establish a fundamental truth. Political economy has only become a science since it has been confined to the results of inductive investigation.

Turgot was himself too good a citizen, not sincerely to esteem as good citizens as the economists; and accordingly, when in power, he deemed it advantageous to countenance them. The economists, in their turn, found their account in passing off so enlightened an individual and minister of state as one of their adepts; the opinions of Turgot, however, were not borrowed from their school, but derived from the nature of things; and although on many important points of doctrine he may have been deceived, the measures of his administration, either planned or executed, are amongst the most brilliant ever conceived by any statesman. There cannot, therefore, be a stronger proof of the incapacity of his sovereign, than his inability to appreciate such exertions, or if capable of appreciating them, in not knowing how to afford them support.

The economists not only exercised a particular sway over French writers, but also had a very remarkable influence over many Italian authors, who even went beyond them. Beccaria, in a course of public lectures at Milan,20 first analysed the true functions of productive capital. The Count de Verri, the countryman and friend of Beccaria, and worthy of being so, both a man of business and an accomplished scholar, in his Meditazione sull' Economia politica, published in 1771, approached nearer than any other writer, before Dr. Smith, to the real laws which regulate the production and consumption of wealth. Filangieri, whose treatise on political and economical laws was not given to the public until the year 1780, appears not to have been acquainted with the work of Dr. Smith, published four years before. The principles de Verri laid down are followed by Filangieri, and even received from him a more complete development; but although guided by the torch of analysis and deduction, he did not proceed from the most fortunate premises to the immediate consequences which confirm them, at the same time that they exhibit their application and utility.

But none of these inquiries could lead to any important result. How, indeed, was it possible to become acquainted with the causes of national prosperity, when no clear or distinct notions had been formed respecting the nature of wealth itself? The object of our investigations must be thoroughly perceived before the means of attaining it are sought after. In the year 1776, Adam Smith, educated in that school in Scotland which has produced so many scholars, historians, and philosophers, of the highest celebrity, published his Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. In this work, its author demonstrated that wealth was the exchangeable value of things; that its extent was proportional to the number of things in our possession having value; and that inasmuch as value could be given or added to matter, that wealth could be created and engrafted on things previously destitute of value, and there be preserved, accumulated, or destroyed.21