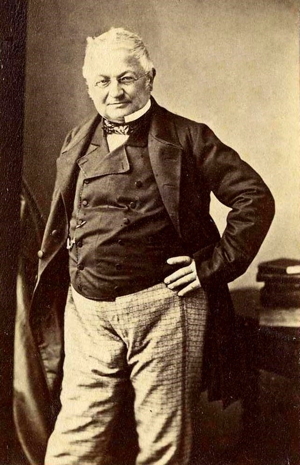

ADOLPHE THIERS,

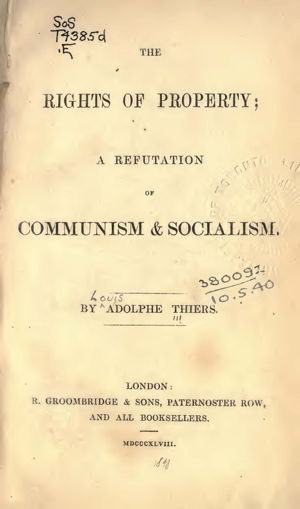

The Rights of Property: A Refutation of Communism & Socialism (1848)

e |

|

| Adolphe Thiers (1797-1877) |

[Created: 9 August, 2014]

[Updated: 9 November, 2023 ] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

, The Rights of Property: A Refutation of Communism & Socialism. By Adolphe Thiers. (London : R. Groombridge & Sons, 1848).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Thiers/Property/index.html

Adolphe Thiers, The Rights of Property: A Refutation of Communism & Socialism. By Adolphe Thiers. (London : R. Groombridge & Sons, Paternoster Row, And All Booksellers. MDCCCXLVIII. (1848)). London : Printed By Waterlow And Sons, 66 & 67 London Wall.

This title is also available in a facsimile PDF of the original [B&W or colour] and various eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub.

See also the French original, simply entitled "De la Propriété" (On Property), in HTML and facs. PDF. Adolphe Thiers, De la Propriété (Paris: Lheureux et Cie., 1848).

This book is part of a collection of works by Adolphe Thiers (1797-1877).

CONTENTS.

BOOK I. ON THE RIGHT OF PROPERTY.

- I. Origin of the Present Controversy 1

- II. Of the Method to be followed 6

- III. On the Universality of Property 10

- IV. On the Faculties of Man 17

- V. On the Employment of Man's Faculties on Labour 21

- VI. On Inequality of Goods 26

- VII. On the Transmission of Property 31

- VIII. On Gift 33

- IX. On Inheritance 35

- X. On the Influence of Inheritance on Labour 39

- XL On the Rich Man 45

- XII. On the True Foundation of the Right of Property 60

- XIII. On Prescription 66

- XIV. On the Invasion of Things by the Extension of Property 74

- I. On the General Principles of Communism 96

- II. On the Conditions inevitable to Communism 98

- III. On Communism with regard to Labour 109

- IV. On Communism with regard to Human Liberty.. 113

- V. On Communism with regard to the Family 119

- VI. On the Cloister, or Life in Common among Christians , 12

- 1. On Socialism 134

- II. On Social Sufferings 139

- III. On Association and its Applicability to the various Classes of Workmen 144

- IV. Of Capital in the System of Association 151

- V. On the Administration of Enterprises in the System of Association 162

- VI. On Piece-work 174

- VII. On the Suppression of Competition 182

- VIII. On Reciprocity 198

- IX. On the Right to Labour 211

- X. On the General Character of the Socialists 220

- I. On the Manner of Reaching Property by Taxation 225

- II. On the Principle of Taxation 227

- III. On the Assessment of Taxation 231

- IV. On the different Forms of Taxation 239

- V. On the Diffusion of Taxation 248

- VI. On the Good and Evil derivable from Taxation.. 256

- VII. On the Evil in the World 269

[v]

ADVERTISEMENT.↩

THE following treatise, intended to refute the dangerous doctrines entertained by a large class of Frenchmen, has recently appeared in the columns of the Constitutionnel ; and as such doctrines are not without their advocates and supporters in our country, it is hoped that this endeavour to present M. Thiers' able work in an English dress, will not be unacceptable to those who may be desirous of gaining information relative to the new movement against Society. Much has been heard of Communism, Socialism, and the Right to Labour, but few, perhaps, are familiar with the meaning of the words. Happily for us their advocates are ignorant and obscure ; yet, as suffering is credulous, they find listeners, whose numbers, according to the testimony of all parties, are rapidly increasing. Such will ever be the case in times of distress : the drowning man catches at a straw ; the starving mechanic is ready for any scheme that promises not only to alleviate but to remove his evils for ever. Fourier, George Sand (Madame Dudevant), Louis Blanc, Cabet, Proudhon, and Considérant are the chief apostles of the new movement : their theories may differ, but their object is the same, — " to suppress the miseries of the people." A most desirable object, and one which should be uppermost in the mind of every statesman and philanthropist ; but the following pages will show to what the schemes of the new school, if carried out, would inevitably lead. [vi] When the poor actually lack their daily bread, is it unnatural that they should listen to the recital of some golden dream, some tale of the Barmecide, if merely to divert their minds from brooding too intensely on their misfortunes? And although each of the multifarious schemes proposed for the re-organization of labour, and the removal of pauperism, contains some weighty points, claiming reflection and consideration, to each is attached such a mass of impracticable phantasies, that common sense rejects them in toto.

M. Thiers' treatise is full of hope ; and while he opposes those who would cut up society, and throw its mangled limbs into the renovating cauldrons of our political Medeas, he deduces the most cheering conclusions from the history of the past. All social improvements must be slow and progressive: as in the physical, so in the political world, violence and destruction go hand in hand. Much of the suffering endured by the working classes may be easily diminished, as it arises from ignorance and bad habits. They are ignorant and do wrong because they know not how to do better; or because they have neither the inclination nor the resolution to do right. In periods of distress, the ignorant labourer thinks to raise his wages by burning his master's ricks, or breaking his machines. Ignorance, during the last visitation of the cholera (and recently at St. Petersburgh) raised the mob against the lives of the physicians, who were endeavouring to stay the progress of the pestilence. Ignorance is the cause of intemperance, and intemperance rums its thousands yearly ; the money spent in the gin-shop or the tap-room would provide a fund for many a "wet day." Remove the ignorance of the people, and you make them provident. Then they will begin to respect themselves, and all virtues follow in the train of self-respect. But the workman cannot do this of himself; it must be done for him by the whole nation embodied in, and represented by, the government. As a [vii] good parent trains up his child to honesty, and virtue, and self-reliance, so should the government, which stands in loco parentis to the State, lead its children in the paths that conduct to happiness and honour.

The chief strength and greatest interest of the treatise we now proceed to lay before the English reader, lie in the rapid and irresistible series of deductions, —a close-linked and brilliant chain of observations and reasoning, which leave no issue for sophistry. The style of the original, which it is almost impossible to transfer to another language, is simple and nervous, lit up now and then by a vivid and touching eloquence, inspired by a profound sentiment of the dignity of human nature, and by a high intelligence of the works of the Creator.

The enemies of the existing state of society have been most active in multiplying the number of their books, and by this means have perverted many minds and deceived many souls. Accordingly it is but right that the defenders of society, in the foremost rank of whom stands M. Thiers, should imitate the zeal of the false philosophers whose doctrines have been so effectually propagated as to procure no less than 66,960 votes in the department of the Seine, for the Communist Raspail, the leader of the tumult of the 15th of May, and a prisoner in Vincennes. The main work, the true policy of the present day, is to strengthen the social principles, and to this M. Thiers has devoted his admirable talents, not only in the tribune by his speech on the Organisation of Labour, but by the present bolder and most original treatise.

In explanation of the concluding words of the author's preface, it may be necessary to observe that General Cavaignac, struck with the ruin caused by false doctrines, requested the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences " to concur in the defence of Social principles, attacked by publications of all sorts, feeling persuaded hat it was not enough to re-establish material order by means [viii] of force, if moral order were not established by means of sound opinions, and that it was necessary to pacify the minds of the people by enlightening them." The Academy accepted the task with alacrity, and on the 12th of August resolved to publish a series of periodical treatises, illustrative of the principles on which are founded the rights of property, the well-being of domestic life, the liberty of nations, and the progress of the world. M. Victor Cousin inaugurated the series by an Essay on Truth and Justice.

[ix]

PREFACE.↩

As society in France has reached that state of moral perturbation, in which ideas the most natural, the most evident, and the most generally recognised, are either doubted or most impudently denied, we may be permitted to demonstrate them as if they required proof. It is a wearisome and difficult task ; for there is nothing more wearisome, nothing more difficult, than the desire of demonstrating evidence. It is put forth, and is not proved. In geometry, for instance, there exist what are called axioms, at which the teacher pauses as he comes to them, and their evidence is allowed to declare itself. Thus the student is told, two parallel lines will never meet each other; and again, the straight line is the shortest line from one point to another. Having arrived at these truths, we reason no longer, we cease all discussion, we allow the clearness of the fact to operate upon the mind, and we spare ourselves the trouble of adding, that if these two lines ever meet, it is because they are not at a constant equal distance from one another ; that is, they are not parallel. In like manner we do not care to add, that if the line traced between two points is not the shortest, [x] it is because it is not straight. In a word, we stop at evidence, we do not go beyond it. i We had attained that point also with regard to certain moral truths, which we considered to be axioms, in consequence of their very clearness. A man labours and receives the reward of his labour; this reward is money; this money he changes into food and clothing; in short, he consumes it, or, if he has too much, he lends it, and interest is paid for it, upon which he lives ; or else, he gives it to whom he pleases, to his wife, children, or friends. We had considered these facts as the simplest, the most legitimate, the most inevitable, the least susceptible of dispute or demonstration. It was not so, however. These facts, we are now told, were acts of usurpation and tyranny. Of the truth of this, a few winters are endeavouring to persuade an excited and suffering multitude ; and while we, relying upon the evidence of certain propositions, allowed the world to go on its way, as it went in the time when a great politician remarked, Il mondo va da se, —we found it undermined by a false science ; and if we wish to prevent society from perishing, we must prove what, out of respect for the human understanding, we should at one time have never thought of demonstrating. Be it so : we must defend society against dangerous sectarians; —we must defend it by force against the armed attempts of their disciples, by reason against their sophisms ; and to that end we must condemn our own mind as well as that of our contemporaries, to a long and methodical demonstration of truths, hitherto the most generally accredited. Yes ! let us confirm those convictions which have been [xi] shaken, by endeavouring to give an account of the most elementary principles. Let us imitate the Dutch, who, when they learn that a devouring insect has began to penetrate their dykes, rush to those dykes to destroy the vermin that is preying on them. Yes ! let us run to the dykes ! Just now it is no question of decorating the homes of our families, but of preventing them from falling into the gulf ; and to do that, we must set our hands to the very foundations by which they are supported.

I shall proceed then to set my hand to the foundations on which society is based. I beg my contemporaries to aid me by their patience, to support me by their attention in the tedious argumentation upon which I shall enter, for their welfare more than for my own ; for having already attained that ripe period, which will in a few years become old age, —having been a witness of several revolutions, —having seen the failure of institutions and characters, —expecting nothing and desiring nothing of any power on earth, —asking Providence only that I may die with honour, if die I must, or live attended by esteem, if my life is spared, I labour not for myself, but for society in peril ; and if, in all that I say, or do, or write, I indulge in a personal feeling, it is, I must confess, owing to the deep indignation inspired by those doctrines, the offspring of the ignorance, pride, and wicked ambition of that faction which aims at rising by destroying, instead of rising by building up. I appeal, therefore, to the patience of my contemporaries. I will endeavour to be clear, brief, and off-hand in proving what they never thought it would be necessary to prove, viz., that what they [xii] earned yesterday is theirs, fairly theirs, and that they are at liberty to support themselves and their children by it. This is the point we have attained, and whither we have been led by false philosophers in coalition with a misguided multitude.

The substance of this work was conceived and drawn up in my mind some three years ago. I repent not having published it then, before the evil had spread its destructive ravages so widely. The pre-occupations of a life, divided between the laborious researches of history and the agitations of politics, alone prevented me. Having retired to the country some three months back, to enjoy the repose which the electors of my native place had procured for me, I drew up this essay, which had only been projected in my mind. The appeal made by the INSTITUTE to all its members, determined me to publish it. I declare, however, that I have not submitted this sketch to the Class of Political and Moral Sciences, to which I belong. I show my obedience to it by this publication; but I by no means render it responsible ; and if I execute its order, it is my own ideas only to which I give utterance, and in my own language free, earnest, and sincere, as it has always been, and always shall be.

Paris, Sept., 1848.

A. THIERS.

ON PROPERTY.

BOOK I.

ON THE RIGHT OF PROPERTY.

[1]

CHAPTER I.

ORIGIN OF THE PRESENT CONTROVERSY.↩

Showing how it has come to pass that property is called in question in our times.

WHAT can have happened, that property, the natural instinct of man, child, and animal, the sole end and indispensable reward of labour, should be called in question ? What can have led to this aberration, unprecedented in any time ar country, not even at Rome, where the contests of the Agrarian Law concerned only the allotment of the lands conquered from the enemy ? What can have done it, we shall see in a few lines.

Towards the close of the last régime, the men who combatted the government of 1830 were divided into several classes. Some, unwilling to destroy, but on the contrary desirous to save, did not place the question in the form of that government, but in its course of proceeding. They demanded real liberty, a liberty guaranteeing the affairs of the commonwealth from the twofold influence of the court and of the streets, a wise [2] financial administration, a powerful organization of the public strength, a prudent but national policy. Others, either from conviction or from zeal, or delighting to distinguish themselves from those against whom they were contending, disliked the very form of the government ; and desired a republic, without daring to give utterance to their wishes. Of the latter, the most sincere consented to wait until the trial of the constitutional monarchy was complete, and they waited with the most perfect good faith. The most ardent, endeavouring to gain distinction even among the republicans, looked forward to a republic with greater impatience ; and, to frame a language for themselves, spoke continually of the interests of the people, interests forgotten, overlooked, and sacrificed. Others, seeking notoriety by still more striking signs, affected to despise all political discussions, called for a social revolution, and, even among the last, there were some who, having a more distant aim, desired a complete and absolute social revolution.

The quarrel became more envenomed as it was protracted ; and at length, when royalty, forewarned too late, would have been willing to transfer the power from one party to the other, in the midst of the general trouble it let the sceptre fall from its hands. It has been taken up. Those who are now its possessors, enlightened by the commencements of experience, are not eager to keep the imprudent engagements which many of them, however, never made. But those who have not the power, and whom no experience has enlightened, persist in demanding a social revolution. A social revolution ! To accomplish this, is it sufficient to will it ? If we had the strength, which may be sometimes acquired by agitating a suffering people, we must find the materials : we must have a society to reform. But if it has been reformed long since, what is to be done ? You emulate the glory of accomplishing a social [3] revolution ; be it so, but you are born sixty years too late ; you should have entered on your career in 1789. Without deceiving, without perverting the people, you would then have had the means of arousing their enthusiasm, and, after arousing, of sustaining it. In those times, every one did not pay taxes. The nobility contributed only a part, the clergy none at all, except when it pleased them to accord voluntary gifts. Every one did not suffer the same penalties for crime : there was the gibbet for some; for others there were a thousand ways of avoiding infamy or death, however richly deserved. All could not, whatever might be their talents, occupy public offices, being prevented some by birth, some by religion. There existed, under the name of feudal rights, a mass of dependences not having their origin in a contract freely entered into, but in a usurpation of the strong over the weak. The peasants were bound to bake their bread at their landlord's oven, grind their corn at his mill, buy exclusively in his markets, suffer the penalties inflicted in his (the manorial) court, and permit their harvests to be devoured by his game. The various trades could not be exercised but by admission into certain companies, and according to the rules laid down by them. Each province had its customs-frontier, with intolerable formalities, for levying the dues. The amount of these was overwhelming. Independently of the enormous estates devolved upon the clergy, an held by mortmain, the cultivators of the soil had pay, under the denomination of tithes, the greater portion of their produce. This concerned the rural population, and for the body of the nation there were censors for those who were tempted to write; the Bastille for the unmanageable ; parliaments for such as Labarre and Galas; [1] and intervals of centuries between the meetings of the StatesGeneral, which might have reformed so many abuses.

[4]

Accordingly, in the immortal night of the 4th of August, 1789, all classes in the nation, nobly represented in the Constituent Assembly, had the power of offering something in sacrifice on the altar of their country. [2] They all had in fact their gift to lay on it : the privileged classes their exemption from taxation, the clergy their wealth, the nobility their feudal rights and their titles, the provinces their separate constitutions. In a word, all classes had a sacrifice to offer, and they did so amidst a joy without example. This joy was, not the joy of a few, but the joy of all, —the joy of a people emancipated from vexations of every kind, —the joy of the third estate upraised from, its humiliation, —the joy even of the nobility, at that time keenly alive to the pleasure of doing good. It was an intoxication without bounds, —a kind of frenzy of humanity, inducing us to embrace the whole world in our ardent patriotism.

For some time past numerous attempts have been made to agitate the popular masses as much as possible. Has the outburst of 1789 been reproduced? Certainly not; and why? Because what has been done, can be done but once ; because in a second 4th of August we should not know what to sacrifice. Does there remain in any quarter a manorial oven or mill to be suppressed? Is there any game which you may not kill, when it comes on your grounds ? Are there any censors, other than an irritated multitude, or the dictatorship which is its representative? Are there any Bastilles ? Are there any disqualifications on account of religious creed or birth ? Is there any elevated post to which you may not aspire ? Is there any inequality beyond that of mind, which is not imputable to the law, or of fortune, which depends on the right of property ? Attempt, if you can, another 4th of August ; erect an altar to your country, and tell us what you will place on it. —Abuses ! [5] Certainly, there is no lack of abuses, and never will be. But a few abuses, on an altar raised to your country, under the open vault of heaven, it is too little ! You must bear other offerings. Seek, then, seek in that society broken up and reconstructed so frequently since '89, and I defy you to discover aught else to sacrifice but property. Accordingly this has not been overlooked, and it is the deplorable origin of the actual controversies on this subject.

All the partisans of a social revolution do not desire, it is true, to sacrifice property to the same degree. Some would abolish it entirely, others in part ; these would be content to remunerate labour in some other way, those would proceed by taxation. But all alike attack property to keep the kind of half-promise they have made to accomplish a social revolution. We must therefore combat all these odious, puerile, ridiculous, but disastrous systems ; sprung, like a swarm of insects, from the decomposition of all governments, and filling the atmosphere in which we live. Such is the origin of this state of things, which will entail upon us, even should society be saved, either the contempt or the compassion of the succeeding generation. God grant that there may be room left for a little esteem in favour of those who may have resisted these errors, the eternal disgrace of the human mind !

CHAPTER II.

OF THE METHOD TO BE FOLLOWED.↩

Showing that the observation of human nature is the true method to be followed in demonstrating the rights of man in society.

BEFORE proceeding to demonstrate that property is a right, a right sacred as the liberty of coming and going, of thinking and writing, it is important to fix on the method of demonstration to be pursued in this matter. When it is said, man has the right of moving, labouring, thinking, and expressing his thoughts freely, what is the foundation for this language ? Whence has the proof of all these rights been derived ? In the wants of man, reply certain philosophers ; his wants constitute his rights. He needs to move freely, to labour in order to live, to think ; when he has thought, to speak in accordance with his thoughts ; therefore he has the right to do these things. Those who reason thus have approached the truth, but not reached it ; from their manner of reasoning it would result —that every want is a right, a true want like a false want, a natural and simple want like one proceeding from perverse habits. If these are true wants, there are also false ones, originating in false habits. Man, by indulging his passions, creates exaggerated and condemnable wants ; such as those of wine, women, expense, dress, idleness, sleep, ill-regulated activity, revolutions, combats, wars. As a man of pleasure, his mistress must be "the cynosure of neighbouring eyes ; " a coarse wine-bibber, he must have hogsheads of drink which will brutalize him ; a, conqueror, he must have the whole world to ravage. [7] If wants were the source of rights, Cæsar at Rome, would have had the right to take the women, the liberty, the wealth, the glory of the Romans, and in that case, vice would have given the right.

I know that the philosophers who have reasoned thus, have distinguished and said, " True wants make rights." It then remains to inquire what are true wants, to distinguish the true from the false, at which end we arrive, how ? by observation of human nature.

The exact observation of human nature is, therefore, the method to be followed in order to discover and demonstrate the rights of man.

Montesquieu has said : " Laws are the relations of things." With due deference to this great genius, he would have spoken with more exactness had he said : " Laws are the permanence of things." Newton observed heavy bodies : he saw an apple fall from a tree (to use popular and familiar language). Comparing this fact with another, with that of the moon attracted towards the earth, of the earth attracted towards tha sun, he perceived in a particular and insignificant fact a general and permanent one, and said : " Heavy bodies are attracted to one another, in proportion to their mass," and called this phenomenon the law of gravitation.

I observe a man ; I compare him with an animal ; I see that, far from obeying vulgar instincts, such as eating, drinking, sleeping, waking, and then repeating the same round, he oversteps these narrow limits, and that to all these natural habitudes he adds others far more elevated, far more complicated. He has a penetrating mind ; with this mind he contrives the means of satisfying his wants ; he makes a selection of these means, not limiting himself to seizing his prey on the wing, like the eagle, or by lying in wait for it, like the tiger; he cultivates the earth, weaves clothing [8] exchanges his own produce with that of another man, traffics, defends or attacks, makes war or peace, rises to the government of states ; then, mounting higher still, attains to a knowledge of God. In proportion to his advance in this various knowledge, he is governed less by brute force and more by reason ; he is worthier of participating in the government of the society of which he is a member ; and all that considered, after having recognised in him the sublime intelligence which is developed by exercise, after having seen that by preventing its exercise I cause him to lose it altogether, making him wretched and almost deserving his wretchedness as a slave, —I express my astonishment and say : " Man has the right to be free, because his noble nature, accurately observed, reveals to me the law, that a thinking being ought to be free ; as the fall of an apple revealed to Newton, that heavy bodies tend towards each other."

I defy then, any one to find any other way of establishing rights than a straight-forward and profound observation of beings. When their constant manner of proceeding has been observed, we infer the law that governs them, and from the law infer the right. Yet I must add one remark to obviate contradiction. " From the law which inclines heavy bodies towards each other," it maybe asked, " do you infer the right ? Will you say : The earth has the right to gravitate towards the sun ? " " No," I reply with Pascal : " Earth, thou knowest not what thou doest. If thou crushest me, thou knowest it not, but I know it. I am then thy superior ! "

No, right is the privilege of moral, of thinking beings. I should almost be tempted to say, but I dare not, that the dog which follows you, and loves you, has the right to be well treated, because that affectionate and attached animal falls down at your feet and licks them tenderly. And yet, were I to express myself [9] thus, I should be wanting in strict accuracy of language. If you owe anything to that faithful creature, it is because you comprehend his wants. As for the dog himself, he has a right to nothing, because he desires without knowledge. This word right has regard solely to themutual relations of thinking beings. All beings, moral as well as physical, have laws in this universe ; but as regards the former, laws constitute rights. After having observed a man, I see that he thinks, that he wants to think, to exercise this faculty ; that by exercise it is developed and enlarged ; and I say that he has the right to think and speak, for thinking and speaking are one. I owe it to him, if I am the government, not as to the dog mentioned above, but as to a being who has the feeling of his right, who is my equal, to whom I give what I know to be his due, and who receives proudly what he knows belongs to him. In a word, it is always the same method, that is to say, the observation of nature. I see that man has such and such a faculty, such and such a want to exercise it. I say that the means must be given him ; and as human language reveals in its infinite shades the infinite shades of things, I say, when speaking of a heavy body, that it tends to gravitate because it is forced thereto. I say of the dog, do not ill-treat him, for he feels your bad treatment, and his amiable nature has not deserved it. Arrived at man, my equal before God, I say, he has the RIGHT. His law, his peculiar law, assumes this sublime word.

[10]

CHAPTER III.

ON THE UNIVERSALITY OF PROPERTY.↩

Showing that property is a permanent fact, universal in all times and in all countries.

THE method of observation being recognised as the only good one for the moral as well as for the physical sciences, I examine, firstly, human nature in every country, in every age, in all states of civilization, and everywhere I find property as a general, universal fact, without any exception.

The publicists of the last century, desirous of making a distinction between the natural and the civil state, imagined an epoch when "wild in woods the naked savage ran," obeying no fixed law, and another epoch in which he had assembled with his fellows and submitted to the restraint of contracts entitled laws. The supposed conditions of the first state were termed natural right; the real and known conditions of the second were styled civil right. This is a mere hypothesis, for man has nowhere and at no time been found isolated, not even among the untutored savages of America or of the islands of the Pacific. As among animals there 'are some which, guided by instinct, live in bodies, (such as herbivorous animals, which graze in company, while carnivorous animals live isolated that they may chase without a rival,) so man has always been observed to live in society. Instinct, that first and oldest of laws, draws him towards his fellows, and constitutes him a social animal. Were it otherwise, what would he do with that intelligent look with which he questions and replies before he can speak ? What would [11] he do with that mind which conceives, generalizes, qualifies things ; with that voice which points them out by sounds ; with that speech, the instrument of thought, the very bond and chain of society ? A being so nobly organized, feeling the want and having the means of communicating with his like, could not be made for isolation. Those wretched inhabitants of Oceania, more nearly resembling the monkey tribe than any others to be met with, occupied with fishing, the least instructive of every kind of existence, have been found drawn near each other, living together, and communicating with one another by harsh and savage sounds.

Nay, more : man has been always found to possess his own dwelling, and in that dwelling his wife and children, forming the first agglomerations, called families ; these being placed in juxta-position to one another form tribes, which by a natural instinct defend one another in common, as they live in common. Observe the stag, the deer, the chamois, grazing quietly in the beautiful glades of our European forests, or on the grassy slopes of the Alps or Pyrenees : if a breath of air carries to their acute senses a sound forewarning them of danger, they give, with voice or foot, a sign of emotion, which is instantly communicated to the whole herd, and they flee in common, for their defence is in the marvellous agility of their legs. Man, born to create and to brave the cannon's mouth, instead of flying, seizes his weapons, be they more or less perfect, takes up a pole, to the end of which he fixes a sharp stone, and armed with this rude lance, unites with his neighbour, opposes the enemy, resists or yields in turn, according to the orders he receives from the most skilful or the most daring member of the tribe.

All these acts are accomplished by instinct, before anything has been written either on laws or acts, before any contract has been thought of. The instinctive rules of this primitive state, —rules the most [12] rudimentary, general, and necessary of all, may well be called natural right. Now property exists from this moment ; for it has never been seen that, in this state, man had not his hut or his tent, his wife, his children, with a few accumulations of the produce of his fishing or hunting, or of his flocks, in the shape of provisions for his family. And if a neighbour, having a precocious instinct of iniquity, should seek to wrest from him some of the simple goods constituting his possessions, he applies to that chief at whose side he has been accustomed to stand during the fight, calls upon him for redress and protection, and the latter decides according to the notions of justice developed among the tribe.

Among every people, then, how rude soever they may be, we find property, at first as a fact and then as an idea, —an idea more or less clear according to the degree of civilization they have attained, but always invariably settled. Thus the savage hunter has at least the property of his bow, his arrows, and of the game he has killed. The nomad, who is a shepherd, has at least the property of his tents, and of his flocks and herds. He has not as yet admitted that of the soil, because as yet he has not thought fit to exert his faculties upon it. But the Arab who has raised numerous herds clearly understands that he is the proprietor of them, and exchanges his produce for the corn which another Arab, already fixed to the soil, has grown elsewhere. He measures with accuracy the value of the object he gives against the value of that which is offered him : he clearly understands that he is the owner (proprietor) of the one before the bargain is struck, and of the other after. To him as yet immovable property has no existence. At times, however, he may be seen, during two or three months of the year, fixing on land which belongs to nobody, tilling it rudely, casting in the seed, gathering it when [13] ripe, and then removing to some other place. But during the time that he is employed in tilling and sowing this land and in harvesting the crop, the nomad feels that he is the owner of it, and would rush to arms against any who should dispute its fruits. His property endures in proportion to his labour. By degrees, however, the wanderer of the desert settles and becomes a husbandman ; for it is in the heart of man to have his home, as a bird has his nest, and the rabbit his burrow. He ends by selecting a territory, by dividing it into patrimonies, where each family settles, labours, cultivates for itself and for its descendants. Just as a man cannot let his affections wander over all the members of his tribe, and that he needs a wife and children of his own, whom he may love, tend, and protect ; in whom are concentrated his fears, his hopes, his life indeed ; he needs a field to himself, which he may cultivate, plant, enclose, or embellish according to his taste, and which he hopes to deliver to his descendants covered with trees that have grown up, not for himself, but for them. Then to the movable property of the nomad succeeds the immovable property of an agricultural people ; the second property arises, and with it complicated laws, indeed, but still such as time renders more just, more foreseeing, but without changing the principle, which is applied by judges and by the public force. Property resulting from a first effect of instinct becomes a social contract, for I protect your property in order that you may protect mine ; I protect it either by my person as a soldier, or by my money, by devoting a part of my revenue to the support of a public force.

Thus man, careless at first, little attached to the soil which affords him wild fruits or numerous animals to devour, without any great trouble to himself, takes his place at nature's table laden with spontaneous viands, and where there is room for all without jealousy or [14] dispute, by turns sitting down, leaving it, and returning to it, as to a banquet always spread by a liberal master, —a master who is none other than God himself. But by degree he acquires a taste for viands more refined ; he must produce them ; he begins to grow attached to them, because they are worth more, because he has had to labour hard to produce them. He thus portions out the earth, becomes strongly attached to his own share, and if nations in a body dispute his right to it, he contends also in nations; if within the city where he dwells, his neighbour disputes his little spot of earth, he pleads before a judge. But his tent and his herds first, his allotment and his farm afterwards, successively attract his affections, and constitute the different modes of his property.

Thus, in proportion as man expands, he becomes more and more attached to what he possesses, or in other words, more proprietary. He is scarcely so at all in a barbarous state ; in the civilized state he is eminently so. It has been said that the idea of property was growing weaker in the world. This is a mistake. Far from being weakened, it is regulated, determined, and strengthened. It ceases, for instance, to be applied to what is not capable of being a possession, that is, to man ; and from that moment slavery ceases. It is a progress in the ideas of justice, not a weakness in the idea of property. For example ; the landlords, the seigneurs, alone had the privilege during the middle ages of killing the game bred on the land belonging to all. Whoever, now-a-days, falls in with a hare on his own grounds may kill it, for it has been bred there. Among the ancients, the land was the property of the republic; in Asia, it belongs to the despot; in the middle ages, it was the property of a few lords. With the progress of the ideas of liberty, by arriving at the enfranchisement of man, his possessions, his goods, were enfranchised also; he was declared proprietor, [15] owner of his land, independently of the republic, the despot, or the lord. From that moment confiscation was abolished. The day that restored to him the use of his faculties, individualized his property still more ; it became still more attached to the individual himself, still more property than it had been.

Let us take another example. In the middle ages, or in despotic states, the surface of the earth was conceded, but not what lay beneath. The right of excavating mines was a royalty, leased out for money and for a season to certain workers of the metals. With the progress of time it was understood, that as the interior of the earth might become the scene of a new kind of labour, it ought to become the scene of a new property, and the property of mines was constituted ; so that now there are two properties connected with the soil, that of the husbandman above, of the miner below.

Property is therefore a general and universal fact, \ increasing and not decreasing. When naturalists obJ serve an animal which, like the bee or the beaver, constructs a habitation, they declare unhesitatingly that the bee and the beaver are constructive animals. On I similar grounds, cannot philosophers, who are the naturalists of the human race, say, and say truly, that property is a law of man, that he is made for property, and that it is a law of his kind ? And it is not enough f to assert that it is a law of his kind, jt is a law of all living things. Has not the rabbit his burrow, the bird his nest, the beaver his hut, and the bee his hive ? Has not the swallow that joy of our climate in the young spring-time her nest, to which she returns, and which she will not yield without a struggle ; and if she had the gift of thought, would she not be disgusted by the theories of our sophists ? Grazing animals live peacefully in a body, like the wanderers of the desert, in certain pastures, from which they never remove, for [16] in them property is manifested by habit. Carnivorous animals, as the lion, like the savage hunter, cannot live in herds ; they would incommode one another ; each has around him a circle of destruction, in which he dwells alone, and from which he expels all of like habits who might wish to share his spoil. He also, if he could think, would declare himself a proprietor. And now, returning to human beings, observe that child, governed by instinct no less than the lion. Notice with what simplicity the inclination for property is revealed in him. I sometimes observe a little boy, sole heir to a considerable fortune, already understanding that he will not have to share with brothers that mansion to which his mother conducts him every summer, —knowing that he is the sole proprietor of that fine park in which his childhood is spent, —he has no sooner arrived, than in these extensive gardens he desires to have his own garden, where he may cultivate fruits which he will not eat, and flowers which he will not gather, but where he will be master —master of a little parcel of the estate until he becomes master of the whole.

After having seen that in all times and in all countries man appropriates all that he touches, first his bow and his arrows, then his land, his house, his palace, —invariably establishes property as the necessary reward of labour, —if we reasoned concerning him, as Pliny and Buffon have reasoned on animals, we should not hesitate to declare, after having observed so general a manner of being, that property is a necessary law of his kind. But this animal is not an ordinary animal ; he is a king, —king of the creation (as would have been said formerly), and yet his titles are contested. This is reasonable ; we must examine them more closely. Fact, it is said, does not constitute right : tyranny also is a fact, a very general fact. We must therefore prove that the fact of property is a right, and deserves the title. We have, however, done something [17] by showing that this fact is increasing instead of diminishing, for tyranny decays and disappears instead of extending. Let us proceed, however, and you will see that this fact is the most deserving of respect, the most fertile of all, the most worthy of being called a right ; for by its means God has civilized the world, and led men from woods and wilds into cities, from cruelty to gentleness, from ignorance to wisdom, from barbarism to civilization.

CHAPTER IV.

ON THE FACULTIES OF MAN.↩

Showing that man possesses in his personal facilities a primary incontestible property, the origin of all others.

PROPERTY, I have said, is a universal fact : let us sub4 mit this fact to the unbiassed judgment of the human, conscience, and examine whether this tendency in man to appropriate either the fish he has caught, the bird he has snared, the fruit he has grown, or the field that he has watered with his sweat, is on his part an act of usurpation, a theft, committed to the injury of the human race.

To leave nothing unexplored, let us begin at home. Let us first consider our own persons, and go as closely as we can. My clothing is very nigh me ; I can, if I have woven or paid him who has woven it, maintain that it is mine ; for to all appearances these garments, which protect me from the wet or the cold, are not such an excess of enjoyment as to be considered prejudicial to the rest of the human race. But I desire to [18] commence still nearer the examination of what does or does not belong to me, and I stay to consider my body, and in my body the living principle by which it is animated.

I feel, I think, I will ; these sensations, these thoughts, this will, I refer to myself. I feel that they are taking place within me, and I regard myself as a being separated from all that surrounds me, distinct from that vast universe which by turns attracts or repels me, charms or amazes me. I feel that I am placed in it, but I distinguish myself clearly from, it, and I confound my person neither with the soil on which I tread, nor with the beings more or less like me who come near me, and with whom I might sometimes be tempted to confound myself, so dear they are to me, —such as my wife and children. I distinguish myself, therefore, from all the rest of the creation, and I feel that I belong to myself.

Let the philosophers who endeavour to search into the reality of our knowledge inquire whether all this spectacle of the universe be true or not, —whether or not the Almighty is making sport of my credulity by placing around me spectres, mere shadows of things, which deceive me, and which have no reality; what has that to do with the subject of which I am treating ? That mass of rock against which my bark founders, —that fiery steed rushing on me to trample me beneath his hoofs, are neither rock nor horse, are a mere image! That rock which threatens my frail boat, that horse which threatens my person ; are sufficient objects of my belief to turn me aside from them : the sensation is sufficient to determine me. From that moment, viewing the spectacle of the world seriously, and leaving to metaphysicians the discussion of its reality, I place myself in that reality, and first appropriate my person, the sensations it experiences, the judgments it forms, the will it conceives ; and I think [19] I may say, without being either tyrant or usurper: the first of my possessions, my properties, is myself.

This recognition once effected, I pass a little from this interior, this centre of my being, —I go forth, and without proceeding far, observe my feet, my hands, my arms. There assuredly I am at the extreme limit of my existence, and I say : These feet, these arms, these hands, incontestibly belong to me. Men may dispute the horses that lend me their active limbs to carry me rapidly over the earth. Perhaps, in the name of the plundered human race, they may be taken from me, and I may be told they do not belong to me, but to all. Well, be it so. But my feet, my hands —no one has yet imagined that they belong to the whole human race. They may tell me so, but I shall not believe it. If any one touched them, or insolently trod upon my feet, I should grow angry, and if strong enough, fall upon the offender to avenge the insult.

These feet, these hands, these varied organs, which put me in communication with the universe, are therefore mine, that is, I make use of them unceasingly, without scruple, without remorse at having the goods of another ; which I never dream of surrendering to any one, unless I desire to aid one that I love, and who is deprived of the use of his limbs. Still, I never confound them with those of another.

Now these feet and hands, which serve me to carry or to seize the objects I want ; these eyes which help me to see ; that mind which helps me to discern all things, and to use them with profit to myself, —these feet, hands, eyes, mind, which are mine and not another's, are they equal to my neighbour's ? Certainly not. I remark in my own faculties and in those of my neighbour very notable differences ; I observe that some, by reason of these differences, are in misery or abundance, unable to defend themselves, or in a position to domineer over others.

[20]

Is it really true that one man has great physical strength, another very little? that one is strong but awkward, another weak but clever ? that one will do but little work, another much ? Is it true that, setting aside the traditional inequalities of birth and fortune, taking two workmen in any manufactory, one will exhibit extreme skill, indefatigable diligence, earn three or four times more than the other, accumulate Ms first gains, and form a capital with which in turn he will speculate and become immensely rich ? These happy faculties, moral or physical, are certainly his own. "This will,, not be denied; and with no misapplication of language, it may be said they are his property. But this property is unequal; for with certain faculties this man remains poor all his life, with certain others that man becomes rich and powerful. They are the essential cause that one has much, the other little.

Here, then, is a primary kind of property, which will not be taxed with usurpation : firstly myself, then my faculties, whether physical or intellectual, my feet, hands, eyes, brain, —in a word, my soul and my body.

This is a primary, incontestable, indivisible property, to which no one has yet thought of applying an agrarian law ; of which no one has ever thought of complaining neither to me, nor to society, nor to its laws ; for which I may be envied or hated, but of which none will ever think of taking away a portion to give it to others, and for which they can complain of God alone, by calling Him unjust, wicked, or powerless, —reproaches, from which I hope to justify Him before the close of this book.

CHAPTER V.

ON THE EMPLOYMENT OF MAN'S FACULTIES, OR LABOUR.↩

Showing, —That by the exercise of man's faculties there is produced a second property, which has labour for its origin, and which society protects for the benefit of all.

A MAN has, therefore, very unequal faculties, relatively to certain members of his race, but which are indisputably his own. Now what shall he do with them ? Has God given them to him, like song to the bird, that he may sing uselessly in the woods, occupy his idleness, or excite the reveries of the solitary wanderer ? One day, perhaps, his voice may be that of a Homer or Tasso, a Demosthenes or Bossuet ; but, meanwhile, God has imposed on him other cares than those of describing nature, or deploring the fall of empires. He has destined him to labour, to labour severely, from sun-rise to 6un-set, to water the earth with the sweat of his brow.

Nudus in nudâ humo, —such is the state in which man was placed on the earth, says Pliny the Elder. By dint of labour man provides for his necessities. He must clothe himself, by tearing from the lion or the tiger the skin which covers them, to hide his own nakedness ; then, as arts are developed, he must spin the fleeces of his sheep, and, weaving the yarn together, form a continuous web to serve him as a garment. This is not sufficient : he must shelter himself from the changes of weather ; construct a dwelling in which he may counteract the irregularities of the seasons, ward [22] off the torrents of rain, the heat of the sun, and the sharp frosts of winter. After having attended to these cares, he must eat, eat every day, several times a-day ; and, while the animal, deprived of reason, but covered with feathers or fur as a protection, finds, if it is a bird, ripe fruit hanging on the trees, if it is a beast of prey, his food prepared in the animals of the pasture, —man is obliged to procure provisions by making them spring out of the ground, or by disputing their possession with animals stronger and fleeter than himself. He must take a branch from the tree, bend it into a bow, discharge from it the winged arrow, which brings down the animal he destines for his meal ; then it must be exposed to the fire, be cooked, —for his stomach is averse to the sight of the blood and the palpitating limbs. Here are bitter fruits, but at their side grow others that are sweeter : he must make a selection from them, that, by cultivation, he may render them still sweeter and more savoury. Of the grains, some are empty or light ; but among the number some are more nourishing than others : some of these he must select, sowing them in a rich soil that will make them more nutritious, and, by cultivation, changing them into wheat. By dint of these cares, man ends by existing, existing tolerably well ; and, with God's help, many revolutions taking place on the earth, empires crumbling one' after the other, generation succeeding generation, mingling with another from the north and the south, the east and the west, exchanging ideas, communicating inventions, daring navigators passing from cape to cape, from the Mediterranean to the ocean, from the ocean to the Indian seas, from Europe to America, collecting, together the productions of the whole world, —the human race attains that point where its misery is changed into wealth, where, instead of the skins of wild beasts, man wears garments of silk and purple, lives on food the most succulent and varied, often the [23] produce of lands situated half the world from the place where they are consumed; and his dwelling, at first little better than the hut of a beaver, assumes the proportions of the Parthenon, the Vatican, or the Tuileries.

That destitute creature, who had nothing . is now in the midst of abundance. By what means ? By labour, indefatigable and intelligent labour.

When he first appears on the earth, he is naked and destitute of all ; but he has faculties, faculties unequally distributed among the beings of his kind ; he employs them, and, by that employment, succeeds in possessing what was deficient, —he becomes the master of the elements, and almost of nature. Man has therefore his faculties to use, not to sport with, as the bird plays with his wings, his beak, or his voice. A time of leisure will some clay arrive ; with that voice he will become a melodious singer ; those feet and hands will be the feet and hands of a skilful dancer ; but he must labour hard and long before he attains this leisure. To this point we are guided by observation of his being, as the observation of the beaver, the sheep, or the lion, leads us to say that the first is a constructive animal, the second a graminivorous, and the third a carnivorous animal.

Let us advance still further. Man must labour. He must, without alternative, that his natural wretchedness may be succeeded by the comforts and enjoyments of civilization. But for whom will you have him labour, for himself or for others ?

My birth-place is an island in the Indian sea. My food is fish. I perceive that at certain hours of the day the fish frequent certain waters. With the twisted fibres of a plant I form a net, which I throw into the water, and draw out filled with fish. Or else my birthplace may be in Asia Minor, near that spot where the ark of Noah rested, and where the grain called wheat was first noticed by man. I am given to agriculture. [24] I force an iron instrument into the earth ; the earth thus disturbed I expose to the fertilizing air ; I scatter the seed over its bosom, and watch while it is growing ; I gather it when ripe, grind it, expose it to the fire, and make bread.

The fish that I have caught with so much patience, the bread that I have made with such exertions, —to whom do they belong ? To me, who have taken such pains, or to the idler who slept while I was toiling at the net or the spade ? The whole human race will reply that they belong to me, for I must live, and on whose labour should I live, if not on my own ? If, just as I was raising to my mouth the bread I had made, some idler should rush upon me and take it away, what should I have to do, but rush in turn on some other, and serving him as I had been served ? He would do the same to a third, and the world, instead of being a theatre of labour, would become a theatre of pillage. And further, as pillage is a sudden and easy act, when we are strong, while production is a slow and difficult act, requiring the employment of a life, plunder would be preferred to fishing, the chase, or cultivation. Man would remain a lion or a tiger, instead of becoming a citizen of Athens, Florence, Paris, or London.

These examples have all been taken from the primitive state of society. But as human nature does not change as it expands, a man may clothe himself in richer apparel, dwell in more sumptuous mansions, live on daintier food, bedeck himself with purple and gold, live in palaces constructed by a Bramante, dine off the most exquisite viands, and uplift his soul to Plato, —his heart has still the same miseries, and requires the same stimulants to rise above them. If he halted a moment in his struggle against nature, she would again become savage. For a brief space, and through a criminal jealousy between two nations, the marvellous road [25] across the Simplon had been neglected, and nature, continually rolling down blocks of ice, showers of snow, and even mere threads, as it were, of water, upon this mountain route, had soon rendered it impassable. If man were to suspend his exertions for a moment, he would be vanquished by nature ; and if, for a single day, he should cease to be urged on by the charms of possession, his arms would fall listlessly down, and he would slumber beside the instruments of his abandoned labour.

All travellers have been struck by the state of languor, misery, and devouring usury of those countries in which property is not sufficiently guaranteed. Travel into the East/,where the despot claims to be the sole proprietor ; or, what comes to the same thing, go back to the middle ages, and you will discern the same features everywhere : the soil neglected because it is the prey most exposed to the greed of tyranny, and reserved for the hands of slaves, who have not the choice of occupation ; commerce preferred, as escaping more easily from exactions ; in commerce, gold, silver, and jewels sought as the property most easily concealed ; all capital ready to be converted into this particular property, and when lent, it is at a most exorbitant rate ; concentrated in the hands of a proscribed class, who, making a public show of their wretchedness, living in houses ruinous without, but sumptuous within, —opposing an invincible obstinacy to the barbarous master that would extort the secret of their treasures —find a recompense in making him pay more for his money, thus avenging tyranny by usury. .

When, on the contrary, either through the course of tune or the wisdom of the ruler, property is respected, at that moment confidence revives, capital resumes its relative importance, the earth again becomes fertile; gold and silver, once so sought for, are now an inconvenient property, and lose their value; their owners [26] have recovered their dignity with security; they no longer conceal their wealth, but show it with confidence, and lend it at a moderate rate of interest. Activity, universal and continuous, prevails ; a general ease follows ; and society, opening like a flower to the dew and the sun, unfolds itself in every direction to the charmed eyes of the beholders. And should there be some who would ascribe this prosperous state of civilized societies to liberty, whose beneficial virtues God forbid that I should dispute, I would reply, that to the respect accorded to property these great results are owing ; for Venice was not free, but as her tyrants respected labour, she became the richest slave on earth.

To resume, then, I say : Man has a primary property in his person and in his faculties ; he has a second, less proximate to his nature, but not less sacred, in the produce of his faculties, which embraces all that is called the goods of this world, and which society is most deeply interested to guarantee ; for without that guarantee there will be no labour ; without labour no civilization, not even the necessaries of life, but wretchedness, robbery, and barbarism.

CHAPTER VI.

ON INEQUALITY OF GOODS.↩

Showing, that the meguality of man's faculties necessarily leads to an inequality of goods.

IT results from the exercise of the human faculties, that, as these faculties are unequal, one man will produce much, another little ; one will be rich, another poor ; in a word, equality will cease to exist in the [27] world. It should be clearly understood that I speak not of that equality which consists in living under the same laws, in obeying the same authorities, incurring the same penalties, obtaining the same rewards, undergoing (in fine) the same social conditions, and which is called equality in the eyes of the law ; but of that equality which would consist in possessing the same amount of property, whether a man be skilful or unskilful, industrious or idle, fortunate or unfortunate in his labour. The former is necessary, indisputable, and, where it is wanting, society is a mere tyranny. Let us see what we should think of the latter.

But first let us return to the fact from which we originally started. These unequal faculties, consisting in greater muscular strength or in greater intellectual energy, in certain aptitudes of body or mind, and sometimes of both, —as in the skilful mechanic, who with his hands adjusts the various parts of a machine, —as in the sculptor, who carves in the marble the idea existing in his mind, —as in the general, whose prompt and sure eye is united with great courage and rude health, —all these faculties, at once physical and moral, belong to the man to whom God gave them. He holds them of God, —of that God whom I will call by what name soever you please, be it god, fatality, chance, —the author, in fact, of all things, either doing them himself or allowing them to be done, either willing or permitting them. You will acknowledge that he is the chief criminal, the main cause of the evil, if evil there be, in the inequalities of which you would be inclined to complain. Even before the time when long accumulated labour, and transmission from generation to generation, has added to the first inequalities, you will acknowledge that even in the savage state the highly gifted man possesses great advantages. In the chase, if he be more skilful, he has twice as much food as his neighbour. In self-defence, if he be stronger, [28] he has twice the means of resistance. Inequality appears, therefore, at the very commencement of the social existence ; it is manifested on the first day. and the ulterior inequalities of the richest society are but the lengthened shadow of a body already highly elevated.

In a question of right, little or much makes no appreciable difference. Equality of goods is or is not the right of the human race : if it is a right, it was as much violated in the younger days of these societies, when the most skilful or most intelligent savage was richest in the productions of the chase, better provided with the means of defence or of subjugating others, as when, in later days, this savage, now a member of a civilized society, is a man of countless wealth, beside a poor man wanting the necessaries of life.

But having recourse to visible facts in order to elicit the will of God, that is, the laws of creation, I affirm that since men are unequally endowed, God has no doubt intended that they should have different enjoyments ; and that when he gave to one a keen sense of hearing, smell, or sight, and to another senses the most obtuse ; to this man the means of producing and eating much, and to that man weak arms and a delicate stomach; when he made one the brilliant Alcibiades, possessing every faculty in perfection, and the other the idiot Crétin, of the valley of Aosta, —he did this that there should be differences in the mode of being in these men, so differently gifted. When, extending my views still farther, I pass from man to the horse or the dog, from the horse or the dog to the mole, the polype, or the plant, —when in the same forest I see the lowly fern beside the lofty oak, and even among these oaks, some more luxuriant than others, which the soil, the sun, the shower have favoured, which have soared proudly above all around, —and then, one more fortunate still, that has escaped the woodman's axe or the lightning's [29] stroke, I say to myself: These inequalities were probably the condition of that sublime plan which a great genius has denned as unity in diversity, and diversity in unity.

But I may be told that this picturesqueness of nature which seduces me may be an injustice, for Cæsar, in the moral order, may be a very interesting object of observation, but he is none the less a tyrant —a seductive tyrant, full of genius, —but still a tyrant.

I understand the objection.

Although we have certainly good grounds for referring to creation itself the principle of all human inequality, yet it is true that God delivers up his own work, charging us to modify or regulate it, as a master delivers to his apprentice a task that he is to finish. Thus, he permitted the existence of a Cæsar, that is, of one man stronger than another, able to oppress the rest ; but he has charged us to restrain this being, to keep him in check by laws.. Well ; but let us see if this tendency to labour much, and consequently to possess much, is one of these despotic tendencies necessary to be kept in check. That is the pith of the matter.

Does that man injure any one who labours energetically and accumulates what he earns ? He toils earnestly, continuously, by the side of another who barely scratches the earth. He possesses well-stored garners by the side of his neighbour whose barns are empty or but half filled. Has he done any harm to this neighbour ? Has he deprived him of his stores ? In that case there would be robbery, violence, evil done to his neighbour. But he has laboured —laboured more or better than another. He has not, therefore, injured him, like a usurper or an oppressor. He has a few more grains on the earth —a little more wealth in society ; and that is all. What harm has he done around him bv enriching himself ? None.

[30]

What interest could society have in preventing him ? None. This prevention, too, would be sheer madness ; for without any corresponding profit, it would have diminished the mass of things necessary or useful to man.

There is, therefore, no harm done either to you or to me, or to society ; and this man should be permitted to exercise his faculties as he pleases.

It is true, nevertheless, that this wealth is a cause of evil to you —the evil of comparison. It galls you, and excites your envy. I agree that this is certainly an evil, a grievous evil, but it is not without compensation ; and all things being soberly examined, society declares the compensation so great that in every time and country it has thought fit to let envy suffer, and the prosperity of individuals increase, in proportion to their skill, and on their application ; —and this is the compensation.

It is by means of exchange that men procure most of the things they require. Accordingly they do not make everything. They make certain things, to which they devote themselves exclusively, and thus succeed in making them better than others. They then give a portion of what they have produced to procure that which the labour of others has produced, and the result is this : when there is more corn or more cloth, both are cheaper. There is more of each for everybody. Whosoever then, by yielding to his taste or his skill in labour, is liable, when he grows rich, to excite your envy, has contributed to the common prosperity, and particularly to yours. If, in consequence of his exertions, there is more corn, or iron, or cloth, or money, there is more of each for all. The abundance which he has helped to create is advantageous to all ; and society permits him to add to his stores, although the result may be an inequality as regards those who labour less strenuously : it is permitted, because the [31] general prosperity increases with his private prosperity. It would check the individual that would oppress his fellows ; but him who employs his faculties to multiply on the soil the objects useful to man, such as food, clothing, or habitations —who renders these objects more plentiful, wholesome, and better, even should he (for himself or his children) convert his aliments into savoury and exquisite viands, his garments into purple and fine linen, his house into a palace —him, I repeat, society encourages and supports, without troubling itself with the contrast ; without compassionating the feelings of the envious ; for even the envious man procures his food, his clothes, his lodging at a cheaper rate, and if he should desire to produce in his turn, he will procure money at a lower interest ; labour will be an easier task to him.

The principle of equality, properly understood, in no respect weakens the principle of property, however unequal that may become by the superiority of one man's labour over another's ; and so far, at least, the chain of our reasoning has been carried on without being weakened.

CHAPTER VII.

ON THE TRANSMISSION OF PROPERTY.↩

Showing that property is not property unless it be transmissible by gift or by inheritance.

NOTHING is more legitimate, say the writers I am arguing against, than that man should enjoy the produce of his labour —that he should eat the fruit gathered from the trees he has planted. They thus grant a [32] personal property to him who has created it by Ms labour. In truth, nature, stronger than they, confounds them ; compels them to be silent in the presence of that fact, so simple, so manifestly irreproachable, of a man eating the fruit that he has caused to grow. They go still further in their concessions ; they admit that a man shall possess more or less, according as he has been during life more or less skilful, more or less industrious, —that one shall have much, another little ; and they grant, consequently, that primary inequality of goods which results from the natural inequality of man's faculties. But here their concessions stop. Nothing is more just, they exclaim, than that a man should enjoy the fruits of his labour ; but that these fruits should be transmitted to another, that this other should enjoy them in idleness, and in the vices that idleness engenders, —this is repugnant to the simplest equity ; this runs counter to the result society had in view by consecrating property, namely, that of exciting labour; this adds to the natural inequalities God has established among men by endowing them unequally, —those artificial inequalities which are the cause that an idle and worthless child, because he is the heir of an industrious and worthy father, lives in the midst of every enjoyment, while at his side another individual, deprived of the same advantages, lives in the greatest misery. Property extended so as to become hereditary thus arrives at consequences which are in contradiction to its principle, and which cannot be admitted.

This is really the point, not a difficult but a complicated one, of the subject under review ; for, like a river, which winds the more the farther it flows from its source, so this question extends, is expanded and mixed up with a multitude of other questions. And yet, what the adversaries of property deny, I affirm ; what they dispute, I maintain to be indispensable ; and these are my assertions as opposed to theirs : —

[33]

Property either is or is not ;

If it is, it carries with it the right of gift ;

If it carries with it the right of gift, it must include the children as well as indifferent persons ;

It is in force during the life of the parent, as well as at his death ;

Far from favouring idleness by this extension, it becomes, on the contrary, a powerful and unlimited excitement to labour, on condition of the privilege of transmitting it from the sire to the son ;

Lastly, the new and the greatest inequalities which follow are absolutely necessary, and compose one of the most beautiful and productive harmonies of human society.

In a word, property produces its best and most productive effects only on condition of being complete, of becoming personal and hereditary.

Such are the propositions which, in the following chapters, I shall endeavour to render so clear as to cut off (I would hope) all opposition.

CHAPTER VIII.

ON GIFT.↩

Showing that gift is one of the necessary manners of using property.

You grant that I can enjoy what I have produced, that I can apply to my wants or my pleasures the fruits of my personal labour. But would it be a robbery, and dangerous to society, if I gave them to another ?

First, suppose that I have produced more than I can consume, which happens to every skilful and industrious [34] man, what will you have me do with the surplus ? My granaries are full of corn, my stores of fruit, and my cellars of wine ; the wool of my flocks has furnished me more garments than I can wear, and all because I have cultivated my fields with more intelligence and activity than another ; what would you have me do with this abundance ? That I should eat and drink more than my hunger and my thirst require, or that I should throw the excess into a lay-stall, appointed for the purpose ; or else that I should not create them at all, which is the simplest course ? If you will not permit me to use the surplus of my labour as I please, I shall be reduced to one of three alternatives : either I must consume more than I want, or destroy the surplus, or not create it at all. But here is a way of employing the superfluity of my goods, which I submit to your judgment.

I observe at the border of my field a poor wretch expiring of hunger and fatigue. I run up to him, and pour into his mouth a little of my surplus wine ; I give him one of those fruits I did not know what to do with ; I throw over his tattered clothes one of those many garments I had produced, and I behold his senses returning, the smile of gratitude imprinted on his features, and in my heart I experience a more lively pleasure than that which I had felt in my mouth when tasting the fruits of my field. Do you mean to restrict to this point the employment of my possessions, so that I cannot use them in the manner that is most pleasing to me ? After having conceded to me the merely physical enjoyment of my property, would you deny me the moral enjoyment, the noblest, the sweetest, the most useful of all ? Odious legislator, you would permit me to eat, to destroy, my possessions, and not allow me to give them away ! Self, self alone, is the paltry aim you would assign to the painful exertions of a life ! you would thus degrade, disenchant, check [35] my labour! But, however, judge of the fact by its consequences. I have said above, that if a man were to fall upon his neighbour, and take away from him the food destined for his support, and he in turn were to do the same to another, society would ere long be a mere scene of plunder, instead of a field of labour. Suppose, on the contrary, that each man who has too much should give to him who has not enough, the world would become a theatre of beneficence. Do not fear, however, that man can ever go too far in this course, and make his neighbour idle by undertaking to labour for him. All the charity that exists in the heart of man is barely on a level with human misery, and the utmost has been done when the continued appeals of morality and religion succeed in making the remedy equal to the disease, the balm sufficient for the wound.

Gift, then, is the noblest way of employing property. It is, I repeat, a moral enjoyment added to a physical enjoyment. " Enough, enough ! " my opponents will say ; " you are demonstrating what needs no demonstration." Agreed : but let us pursue the matter, and they will perhaps be obliged to say as much of all the rest.

CHAPTER IX.

ON INHERITANCE.↩

Showing that from gift the parent derives the right of endowing his children during his life or at his death.

IT has been conceded, that gift is one of the necessary and indispensable ways of employing property. Now let us go a step farther. What ! I may give to persons who are nothing to me, but whose sufferings have touched me, and I cannot give to my wife or children ; [36] to my wife, who shared all the toils of my life ; to my children, my offspring, who are dearer to me than my own person ! When they are hungry or cold, if I am not utterly depraved, I feel hunger and cold more for them than for myself. Their wants are mine, and stimulate me more than my own. Will you not then permit me to make a choice among my wants, to satisfy first those which I feel the most acutely, and to appease a hunger more painful for me to endure than that which I feel in my own stomach ? You will permit me, then, to feed my children before I feed myself. That is not all, however. For a part of their life, some one must support these children, for during onefourth of their existence they are too weak to provide for themselves. In the savage state, for instance, trees must be climbed to gather fruit ; in a civilized state, bread can only be procured after it is earned. But if any one should support them, who will undertake that care, unless it be myself, their father, the author of their days ? The birds of the air set me an example, which, apparently, you will allow me to follow ! " Enough, enough ! " my opponents will say again ; " you are proving what requires no proof ! " Where then must I go in this road to find what needs a demonstration ?

Property is not property, if I cannot give it away as well as consume it : this point is conceded. If I can give it to strangers, a fortiori I can give it to my children, who imperatively require it during part of their life : this is also conceded. I can therefore give it to another, and in another I can, I ought to prefer my children. Where then does the difficulty begin ? At the moment of my decease ; that is, I can give it at all periods of my life, except at the point of death. And is that the only difference between the right I claim and that which is disputed ! But this difference would be either null, or barbarous, or impossible.

[37]