JAMES HARRINGTON,

The Oceana and Other Works (1771)

|

|

| James Harrington (1611–1677) |

[Created: 30 August, 2021]

[Updated: 10 January, 2024 ] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

, The Oceana and Other Works of James Harrington, with an Account of His Life by John Toland (London: Becket and Cadell, 1771).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Levellers/Harrington/1771-Works/index.html

The Oceana and Other Works of James Harrington, with an Account of His Life by John Toland (London: Becket and Cadell, 1771).

This title is also available in a facsimile PDF of the original and various eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub.

This book is part of a collection of works by James Harrington (1611–1677).

CONTENTS.

- 1. TOLAND’s Dedication to the Lord-Mayor, Aldermen, Sheriffs, and Common-Council of the City of London. — — Page i

- 2. His Preface. — — — vii

- 3. The Life of James Harrington. — — xi

- I. The Grounds and Reasons of Monarchy considered, and exemplified in the Scotish Line, out of their own best Authors and Records. (Written by John Hall of Gray’s Inn, Esq;) — — 1

- II. The Commonwealth of Oceana. (First printed in London in the Year 1656 in fol.) 31

- III. The Prerogative of popular Government. (First printed at London in 1658 in 4to.) — — — 213

- IV. The Art of Lawgiving. (First printed at London 1659, in 8vo.) — 359

- V. A Word concerning a House of Peers. (First printed at London 1659, in 8vo.) 439

- Six Political Tracts written on several occasions

- VI. Valerius and Publicola, or the true Form of a Popular Commonwealth extracted è puris Naturalibus. (First printed in 1659, in 4to.) — 445

- VII. A System of Politics delineated in short and easy Aphorisms. (First published from the Author’s own Manuscript by Mr. Toland, with his Oceana and other Works, at London in 1700, in fol.) — — 465

- VIII. Political Aphorisms. (First printed at London 1659, in 4to.) — 483

- IX. Seven Models of a Commonwealth, or brief Directions shewing how a fit and perfect Model of popular Government may be made, found, or understood. (First printed at London 1659, in 4to.) — — 491

- X. The Ways and Means whereby an equal and lasting Commonwealth may be suddenly introduced, and perfectly founded, with the free Consent and actual Confirmation of the whole People of England. (First printed at London 1660, in 4to.) — 506

- XI. The humble Petition of divers well-affected Persons delivered the 6th of July 1659, with the Parliament’s Answer thereto. — — 508

- APPENDIX, containing all the political Tracts of James Harrington Esq; omitted in Mr. Toland’s Edition of his Works.

- XII. Pian Piano, or, Intercourse between H. Ferne, D. D. and J. Harrington, Esq; upon occasion of the Doctor’s Censure of the Commonwealth of Oceana. (First printed at London 1656, in 12mo.) — — 517 [none]

- XIII. The Stumbling-Block of Disobedience and Rebellion, cunningly imputed by P. H. unto Calvin, removed; in a Letter to the said P. H. from J. H. (First printed at London 1659, in 4to.) — — — 534

- XIV. A Letter unto Mr. Stubs, in Answer to his Oceana weighed, &c. (First printed at London 1659, in 4to.) — — 542

- XV. Politicaster, or a comical Discourse, in answer to Mr. Wren’s Book, intitled, Monarchy afferted against Mr. Harrington’s Oceana. (First printed at London 1659, in 12mo.) — — 546

- XVI. Pour enclouer le Canon. (First printed at London 1659, in 4to.) — 562

- XVII. A Discourse upon this Saying, The Spirit of the Nation is not yet to be trusted with Liberty, lest it introduce Monarchy, or invade the Liberty of Conscience. (First printed at London 1659, in 4to.) — 567

- XVIII. A Discourse shewing that the Spirit of Parlaments, with a Council in the Intervals, is not to be trusted for a Settlement, lest it introduce Monarchy and Persecution for Conscience. (First printed at London 1659, in 4to.) — 575

- XIX. A Parallel of the Spirit of the People, with the Spirit of Mr. Rogers; and an Appeal thereupon unto the Reader, whether the Spirit of the People, or the Spirit of Men like Mr. Rogers, be the fitter to be trusted with the Government. (First printed at London 1659, in 4to.) — — — 580

- XX. A sufficient Answer to Mr. Stubs. (First printed at London 1659, in 4to.) 584

- XXI. A Proposition in order to the proposing of a Commonwealth or Democracy. (First printed at London 1659, in fol.) — — 586

- XXII. The Rota, or a Model of a free State or equal Commonwealth, once proposed and debated in brief, and to be again more at large proposed to, and debated by a free and open Society of ingenious Gentlemen. (First printed at London 1660, in 4to.) 587

- Endnotes

respublica, res est populi cum bene ac iuste geritur, sive ab uno rege, sive a paucis optimatibus, sive ab universo populo. cum vero iniustus est rex, quem tyrannum voco, aut iniusti optimates, quorum consensus factio est, aut iniustus ipse populus, cui nomen usitatum nullum reperio nisi ut ipsum tyrannum appellem, non iam vitiosa sed omnino nulla respublica est, quoniam non res est populi cum tyrannus eam factiove capessat; nec ipse populus iam populus est si sit iniustus, quoniam non est multitudo iuris consensu et utilitatis communione sociata.

fragmentum ciceronis, ex lib. iii. de republica, apud augustin. de civ. dei, l. ii. c. xxi.

Advertisement to the Reader. ↩

THE Reputation of Mr. Harrington’s Writings is so well established, that nothing more is necessary than to acquaint the Reader, that no Expence nor Care have been spared to make the former and present Edition as complete as possible. They contain the whole of Mr. Toland’s Edition, which was become extremely scarce, and sold at a very high Price. To these are added the several political Pieces of our Author, which Mr. Toland thought proper to omit in his Edition: a Liberty which few Readers will excuse. Most of these Pieces were republished by Mr. Harrington at London, in one Volume in Quarto, in 1660, under the general Title of Political Discourses, tending to the Introduction of a free and equal Commonwealth in England.

I take this opportunity of acknowledging my Obligation to the Rev. Mr. Thomas Birch, F. R. S. for obliging the Publick with the Political Discourses above-mentioned.

[i]

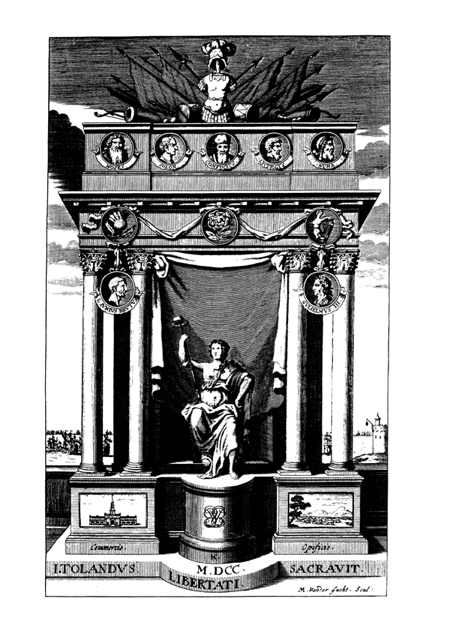

TO THE LORD MAYOR, ALDERMEN, SHERIFS, AND COMMON COUNCIL OF LONDON. ↩

IT is not better known to you, most worthy magistrats, that government is the preserving cause of all societys, than that every society is in a languishing or flourishing condition, answerable to the particular constitution of its government: and if the goodness of the laws in any place be thus distinguishable by the happiness of the people, so the wisdom of the people is best discern’d by the laws they have made, or by which they have chosen to be govern’d. The truth of these observations is no where more conspicuous than in the present state of that most antient and famous society you have the honor to rule, and which reciprocally injoys the chearful influence of your administration. ’Tis solely to its government that London ows being universally acknowleg’d the largest, fairest, richest, and most populous city in the world; all which glorious attributes could have no foundation in history or nature, if it were not likewise the most free. ’Tis confest indeed that it derives infinite advantages above other places from its incomparable situation, as being an inland city, seated in the middle of a vale no less delicious than healthy, and on the banks of a noble river, in respect of which (if we regard how many score miles it is navigable, the clearness and depth of its channel, or its smooth and even course) the Seine is but a brook, and the celebrated Tyber it self a rivulet: yet all this could never raise it to any considerable pitch without the inestimable blessings of Liberty, which has chosen her peculiar residence, and more eminently fixt her throne in this place. Liberty is the true [ii] spring of its prodigious trade and commerce with all the known parts of the universe, and is the original planter of its many fruitful colonys in America, with its numberless factorys in Europe, Asia, and Africa: hence it is that every sea is cover’d with our ships, that the very air is scarce exemted from our inventions, and that all the productions of art or nature are imported to this common storehouse of mankind; or rather as if the whole variety of things wherwith the earth is stockt had bin principally design’d for our profit or delight, and no more of ’em allow’d to the rest of men, than what they must necessarily use as our purveyors or laborers. As Liberty has elevated the native citizens of London to so high a degree of riches and politeness, that for their stately houses, fine equipages, and sumtuous tables, they excede the port of som foren princes; so is it naturally becom every man’s country, and the happy refuge of those in all nations, who prefer the secure injoyment of life and property to the glittering pomp and slavery, as well as to the arbitrary lust and rapine of their several tyrants. To the same cause is owing the splendor and magnificence of the public structures, as palaces, temples, halls, colleges, hospitals, schools, courts of judicature, and a great many others of all kinds, which, tho singly excel’d where the wealth or state of any town cannot reach further than one building, yet, taking them all together, they are to be equal’d no where besides. The delicat country seats, and the large villages crouded on all hands around it, are manifest indications how happily the citizens live, and makes a stranger apt to believe himself in the city before he approaches it by som miles. Nor is it to the felicity of the present times that London is only indebted: for in all ages, and under all changes, it ever shew’d a most passionat love of Liberty, which it has not more bravely preserv’d than wisely manag’d, infusing the same genius into all quarters of the land, which are influenc’d from hence as the several parts of the animal body are duly supply’d with blood and nourishment from the heart. Whenever therfore the execrable design was hatcht to inslave the inhabitants of this country, the first attemts were still made on the government of the city, as there also the strongest and most successful efforts were first us’d to restore freedom: for we may remember (to name one instance for all) when the late king was fled, and every thing in confusion, that then the chief nobility and gentry resorted to Guildhall for protection, and to concert proper methods for settling the nation hereafter on a basis of liberty never to be shaken. But what greater demonstration can the world require concerning the excellency of our national government, or the particular power and freedom of this city, than the Bank of England, which, like the temple of Saturn among the Romans, is esteem’d so sacred a repository, that even soreners think their treasure more safely lodg’d there than with themselves at home; and this not only don by the [iii] subjects of absolute princes, where there can be no room for any public credit, but likewise by the inhabitants of those commonwealths where alone such banks were hitherto reputed secure. I am the more willing to make this remark, because the constitution of our bank is both preferable to that of all others, and comes the nearest of any government to Harrington’s model. In this respect a particular commendation is due to the city which produc’d such persons to whose wisdom we owe so beneficial an establishment: and therfore from my own small observation on men or things I fear not to prophesy, that, before the term of years be expir’d to which the bank is now limited, the desires of all people will gladly concur to have it render’d perpetual. Neither is it one of the last things on which you ought to value your selves, most worthy citizens, that there is scarce a way of honoring the deity known any where, but is either already allow’d, or may be safely exercis’d among you; toleration being only deny’d to immoral practices, and the opinions of men being left as free to them as their possessions, excepting only Popery, and such other rites and notions as directly tend to disturb or dissolve society. Besides the political advantages of union, wealth, and numbers of people, which are the certain consequents of this impartial liberty, ’tis also highly congruous to the nature of true religion; and if any thing on earth can be imagin’d to ingage the interest of heaven, it must be specially that which procures it the sincere and voluntary respect of mankind. I might here display the renown of the city for military glory, and recite those former valiant atchievments which our historians carefully record; but I should never finish if I inlarg’d on those things which I only hint, or if I would mention the extraordinary privileges which London now injoys, and may likely possess hereafter, for which she well deserves the name of a New Rome in the West, and, like the old one, to becom the soverain mistress of the universe.

The government of the city is so wisely and completely contriv’d, that Harrington made very few alterations in it, tho in all the other parts of our national constitution he scarce left any thing as he found it. And without question it is a most excellent model. The lord mayor, as to the solemnity of his election, the magnificence of his state, or the extent of his authority, tho inferior to a Roman consul (to whom in many respects he may be fitly compar’d) yet he far outshines the figure made by an Athenian archon, or the grandeur of any magistrat presiding over the best citys now in the world. During a vacancy of the throne he is the chief person in the nation, and is at all times vested with a very extraordinary trust, which is the reason that this dignity is not often confer’d on undeserving persons; of which we need not go further for an instance than the Right Honorable Sir Richard Levet, who now so worthily fills that eminent post, into which he was not more freely chosen by the suffrages of his fellow-citizens, [iv] than he continues to discharge the functions of it with approv’d moderation and justice. But of the great caution generally us’d in the choice of magistrats, we may give a true judgment by the present worshipful sherifs, Sir Charles Duncomb and Sir Jeffery Jefferies, who are not the creatures of petty factions and cabals, nor (as in the late reigns) illegally obtruded on the city to serve a turn for the court, but unanimously elected for those good qualitys which alone should be the proper recommendations to magistracy; that as having the greatest stakes to lose they will be the more concern’d for securing the property of others, so their willingness to serve their country is known not to be inferior to their zeal for king William; and while they are, for the credit of the city generously equalling the expences of the Roman prætors, such at the same time is their tender care of the distrest, as if to be overseers of the poor were their sole and immediat charge. As the common council is the popular representative, so the court of aldermen is the aristocratical senat of the city. To enter on the particular merits of those names who compose this illustrious assembly, as it must be own’d by all to be a labor no less arduous than extremely nice and invidious, yet to pass it quite over in such a manner as not to give at least a specimen of so much worth, would argue a pusillanimity inconsistent with Liberty, and a disrespect to those I wou’d be always understood to honor. In regard therfore that the eldest alderman is the same at London with what the prince of the senat was at Rome, I shall only presume to mention the honorable Sir Robert Clayton as well in that capacity, as by reason he universally passes for the perfect pattern of a good citizen. That this character is not exaggerated will be evident to all those who consider him, either as raising a plentiful fortune by his industry and merit, or as disposing his estate with no less liberality and judgment than he got it with honesty and care: for as to his public and privat donations, and the provision he has made for his relations or friends, I will not say that he is unequal’d by any, but that he deserves to be imitated by all. Yet these are small commendations if compar’d to his steddy conduct when he supply’d the highest stations of this great city. The danger of defending the liberty of the subject in those calamitous times is not better remember’d than the courage with which he acted, particularly in bringing in the bill for excluding a Popish successor from the crown, his brave appearance on the behalf of your charter, and the general applause with which he discharg’d his trust in all other respects; nor ought the gratitude of the people be forgot, who on this occasion first stil‘d him the father of the city, as Cicero for the like reason was the first of all Romans call’d the father of his country. That he still assists in the government of London as eldest alderman, and in that of the whole nation as a member of the high court of parlament, is not so great an honor as that [v] he deserves it; while the posterity of those familys he supports, and the memory of his other laudable actions, will be the living and eternal monuments of his virtue, when time has consum’d the most durable brass or marble.

To whom therfore shou’d I inscribe a book containing the rules of good polity, but to a society so admirably constituted, and producing such great and excellent men? that elsewhere there may be found who understand government better, distribute justice wiser, or love liberty more, I could never persuade myself to imagin: nor can the person wish for a nobler address, or the subject be made happy in a more suitable patronage than THE SENAT AND PEOPLE OF LONDON; to whose uninterrupted increase of wealth and dignity, none can be a heartier welwisher, than the greatest admirer of their constitution, and their most humble servant,

JOHN TOLAND.

[vi]

[vii]

THE PREFACE. ↩

HOW allowable it is for any man to write the history of another, without intitling himself to his opinions, or becoming answerable for his actions, I have expresly treated in the Life of John Milton, and in the just defence of the same under the title of AMYNTOR. The reasons there alleg’d are excuse and authority enough for the task I have since impos’d on my self, which is, to transmit to posterity the worthy memory of James Harrington, a bright ornament to useful learning, a hearty lover of his native country, and a generous benefactor to the whole world; a person who obscur’d the false lustre of our modern politicians, and that equal’d (if not exceded) all the antient legislators.

BUT there are some people more formidable for their noise than number, and for their number more considerable than their power, who will not fail with open mouths to proclaim, that this is a seditious attemt against the very being of monarchy, and that there’s a pernicious design on foot of speedily introducing a republican form of government into the Britannic islands; in order to which the person (continue they) whom we have for som time distinguisht as a zealous promoter of this cause, has now publisht the Life and Works of Harrington, who was the greatest commonwealthsman in the world. This is the substance of what these roaring and hoarse trumpeters of detraction will sound; for what’s likely to be said by men, who talk all by rote, is as easy to guess as to answer, tho ’tis commonly so silly as to deserve no animadversion. Those who in the late reigns were invidiously nicknam’d Commonwealthsmen, are by this time sufficiently clear’d of that imputation by their actions, a much better apology than any words: for they valiantly rescu’d our antient government from the devouring jaws of arbitrary power, and did not only unanimously concur to fix the imperial crown of England on the most deserving head in the universe, but also settl’d the monarchy for the future, not as if they intended to bring it soon to a period, but under such wife regulations as are most likely to continue it for ever, consisting of such excellent laws as indeed set bounds to the will of the king, but that render him thereby the more safe, equally binding up his and the subjects hands from unjustly seizing one another’s prescrib’d rights or privileges.

’T IS confest, that in every society there will be always found som persons prepar’d to enterprize any thing (tho never so flagitious) grown desperat by their villanies, their profuseness, their ambition, or the more raging madness of superstition; and this evil is not within the compass of art or nature to remedy. But that a whole people, or any considerable number of them, shou’d rebel against a king that well and wisely administers his government, as it cannot be instanc’d out of any history, so it is a thing in it self impossible. An infallible expedient therfore to exclude a commonwealth, is for the king to be the man of his people, and, according to his present Majesty’s glorious example, to find out the secret of so happily uniting two seemingly incompatible things, principality and liberty.

[viii]

’TIS strange that men shou’d be cheated by mere names! yet how frequently are they seen to admire one denomination, what going under another they wou d undoubtedly detest; which observation made Tacitus lay down for a maxim, That the secret of setting up a new state consists in retaining the image of the old. Now if a commonwealth be a government of laws enacted for the common good of all the people, not without their own consent or approbation; and that they are not wholly excluded, as in absolute monarchy, which is a government of men who forcibly rule over others for their own private interest: then it is undeniably manifest that the English government is already a commonwealth, the most free and best constituted in all the world. This was frankly acknowleg’d by King James the First, who stiled himself the great servant of the commonwealth. It is the language of our best lawyers, and allow’d by our author, who only makes it a less perfect and more inequal form than that of his Oceana, wherin, he thinks, better provision is made against external violence or internal diseases. Nor dos it at all import by what names either persons, or places, or things, are call’d, since the commonwealthsman finds he injoys liberty under the security of equal laws, and that the rest of the subjects are fully satisfy’d they live under a government which is a monarchy in effect as well as in name. There’s not a man alive that excedes my affection to a mixt form of government, by the antients counted the most perfect; yet I am not so blinded with admiring the good constitution of our own, but that every day I can discern in it many things deficient, som things redundant, and others that require emendation or change. And of this the supreme legislative powers are so sensible, that we see nothing more frequent with them than the enacting, abrogating, explaining, and altering of laws, with regard to the very form of the administration. Nevertheless I hope the king and both houses of parlament will not be counted republicans; or, if they be, I am the readiest in the world to run the same good or bad fortune with them in this as well as in all other respects.

BUT, what Harrington was oblig’d to say on the like occasion I must now produce for my self. It was in the time of Alexander, the greatest prince and commander of his age, that Aristotle (with scarce inferior applause, and equal fame) wrote that excellent piece of prudence in his closet which is call’d his Politics, going upon far other principles than Alexander’s government, which it has long outliv’d. The like did Livy without disturbance in the time of Augustus, Sir Thomas More in that of Henry the Eighth, and Machiavel when Italy was under princes that afforded him not the ear. If these and many other celebrated men wrote not only with honor and safety, but even of commonwealths under despotic or tyrannical princes, who can be so notoriously stupid as to wonder that in a free government, and under a king that is both the restorer and supporter of the liberty of Europe, I shou’d do justice to an author who far outdos all that went before him, in his exquisit knowlege of the politics?

THIS liberty of writing freely, fully, and impartially, is a part of those rights which in the last reigns were so barbarously invaded by such as had no inclination to hear of their own enormous violations of the laws of God and man; nor is it undeserving observation, that such as raise the loudest clamors against it now, are the known enemys of King William’s title and person, being sure that the abdicated King James can never be reinthron’d so long as the press is open for brave and free spirits to display the mischiefs of tyranny in their true colors, and to shew the infinit advantages of liberty. But not to dismiss even such unreasonable people without perfect satisfaction, let ’em know that I don’t recommend a commonwealth, but write the history of a commonwealthsman, fairly divulging the principles and pretences of that party, and leaving every body to approve or [ix] dislike what he pleases, without imposing on his judgment by the deluding arts of sophistry, eloquence, or any other specious but unfair methods of persuasion. Men, to the best of their ability, ought to be ignorant of nothing; and while they talk so much for and against a commonwealth, ’tis fit they shou’d at least understand the subject of their discourse, which is not every body’s case. Now as Harrington’s Oceana is, in my opinion, the most perfect form of popular government that ever was; so this, with his other writings, contain the history, reasons, nature and effects of all sorts of government, with so much learning and perspicuity, that nothing can be more preferably read on such occasions.

LET not those therfore, who make no opposition to the reprinting or reading of Plato’s Heathen commonwealth, ridiculously declaim against the better and Christian model of Harrington; but peruse both of ’em with as little prejudice, passion, or concern, as they would a book of travels into the Indys for their improvement and diversion. Yet so contrary are the tempers of many to this equitable disposition, that Dionysius the Sicilian tyrant, and such beasts of prey, are the worthy examples they wou’d recommend to the imitation of our governors, tho, if they cou’d be able to persuade ’em, they wou’d still miss of their foolish aim: for it is ever with all books, as formerly with those of Cremutius Cordus, who was condemn’d by that monster Tiberius for speaking honorably of the immortal tyrannicides Brutus and Cassius. Tacitus records the last words of this historian, and subjoins this judicious remark: The senat, says he, order’d his books to be burnt by the ediles; but som copys were conceal’d, and afterwards publish’d; whence we may take occasion to laugh at the sottishness of those who imagin that their present power can also abolish the memory of succeding time: for, on the contrary, authors acquire additional reputation by their punishment; nor have foren kings, and such others as have us’d the like severity, got any thing by it, except to themselves disgrace, and glory to the writers. But the works of Harrington were neither supprest at their first publication under the usurper, nor ever since call’d in by lawful authority, but as inestimable treasures preserv’d by all that had the happiness to possess ’em intire; so that what was a precious rarity before, is now becom a public good, with extraordinary advantages of correctness, paper, and print. What I have perform’d in the history of his life, I leave the readers to judg for themselves; but in that and all my other studys, I constantly aim’d as much at least at the benefit of mankind, and especially of my fellow citizens, as at my own particular entertainment or reputation.

THE politics, no less than arms, are the proper study of a gentleman, tho he shou’d confine himself to nothing, but carefully adorn his mind and body with all useful and becoming accomplishments; and not imitat the servile drudgery of those mean spirits, who, for the sake of som one science, neglect the knowlege of all other matters, and in the end are many times neither masters of what they profess, nor vers’d enough in any thing else to speak of it agreably or pertinently: which renders ’em untractable in conversation, as in dispute they are opinionative and passionate, envious of their fame who eclipse their littleness, and the sworn enemys of what they do not understand.

BUT Heaven be duly prais’d, learning begins to flourish again in its proper soil among our gentlemen, in imitation of the Roman patricians, who did not love to walk in leading-strings, and to be guided blindfold, nor lazily to abandon the care of their proper business to the management of men having a distinct profession and interest: for the greatest part of their best authors were persons of consular dignity, the ablest statesmen, [x] and the most gallant commanders. Wherfore the amplest satisfaction I can injoy of this sort will be, to find those delighted with reading this work, for whose service it was intended by the author; and which, with the study of other good books, but especially a careful perusal of the Greec and Roman historians, will make ’em in reality deserve the title and respect of gentlemen, help ’em to make an advantageous figure in their own time, and perpetuat their illustrious fame and solid worth to be admir’d by future generations.

AS for my self, tho no imployment or condition of life shall make me disrelish the lasting entertainment which books afford; yet I have resolv’d not to write the life of any modern person again, except that only of one man still alive, and whom in the ordinary course of nature I am like to survive a long while, he being already far advanc’d in his declining time, and I but this present day beginning the thirtieth year of my age.

Canon near Banstead, Novemb. 30. 1699.

[xi]

THE LIFE OF JAMES HARRINGTON. ↩

1. JAMES HARRINGTON (who was born in January 1611) was descended of an antient and noble family in Rutlandshire, being great grandson to Sir James Harrington; of whom it is observ’d by the [2] historian of that county, that there were sprung in his time eight dukes, three marquisses, seventy earls, twenty-seven viscounts, and thirty-six barons; of which number sixteen were knights of the garter: to confirm which account, we shall annex a copy of the inscription on his monument and that of his three sons at Exton, with notes on the same by an uncertain hand. As for our author, he was the eldest son of Sir Sapcotes Harrington, and Jane the daughter of Sir William Samuel of Upton in Northamptonshire. His father had children besides him, William, a merchant in London; Elizabeth, marry’d to Sir Ralph Ashton in Lancashire, baronet; Ann, marry’d to Arthur Evelyn, Esq; And by a second wife he had John, kill’d at sea; Edward, a captain in the army, yet living; Frances, marry’d to John Bagshaw of Culworth in Northamptonshire, Esq; and Dorothy, marry’d to Allan Bellingham of Levens in Westmorland, Esq; This lady is still alive, and, when she understood my design, was pleas’d to put me in possession of all the remaining letters, and other manuscript papers of her brother, with the collections and observations relating to him, made by his other sister the lady Ashton, a woman of very extraordinary parts and accomplishments. These, with the account given of him by Anthony Wood, in the second volum of his Athenae Oxonienses, and what I cou’d learn from the mouths of his surviving acquaintance, are the materials whereof I compos’d this insuing history of his life.

2. In his very childhood he gave sure hopes of his future abilitys, as well by his inclination and capacity to learn whatever was propos’d to him, as by a kind of natural gravity; whence his parents and masters were wont to say, That he rather kept them in aw, than needed their correction: yet when grown a man, none could easily surpass him for quickness of wit, and a most facetious temper. He was enter’d a gentleman commoner of Trinity College in Oxford in the year 1629, and became a pupil to that great master of reason Dr. Chillingworth, who discovering the errors, impostures, and tyranny of the Popish church (whereof he was for some time a member) attackt it with more proper and successful arms than all before, or perhaps any since have don. After considerably improving his knowlege in the university, he was more particularly fitting himself for his intended travels, by learning several foren languages, when his father dy’d, leaving him under [xii] age. Tho the court of wards was still in being, yet by the soccage tenure of his estate he was at liberty to chuse his own guardian; and accordingly pitch’d upon his grandmother the lady Samuel, a woman eminent for her wisdom and virtue. Of her and the rest of his governors he soon obtain’d a permission to satisfy his eager desire of seeing som other parts of the world, where he could make such observations on men and manners, as might best fit him in due time to serve and adorn his native country.

3. His first step was into Holland, then the principal school of martial disciplin, and (what toucht him more sensibly) a place wonderfully flourishing under the influence of their liberty, which they had so lately asserted, by breaking the yoke of a severe master, the Spanish tyrant. And here, no doubt, it was that he begun to make government the subject of his meditations: for he was often heard to say, that, before he left England, he knew no more of monarchy, anarchy, aristocracy, democracy, oligarchy, or the like, than as hard words, wherof he learnt the signification in his dictionary. For some months he listed himself in my lord Craven’s regiment and Sir Robert Stone’s; during which time being much at the Hague, he had the opportunity of further accomplishing himself in two courts, namely, those of the prince of Orange and the queen of Bohemia, the daughter of our K. James I. then a fugitive in Holland, her husband having bin abandon’d by his father in law, betray’d by the king of Spain, and stript of all his territorys by the emperor. This excellent princess entertain’d him with extraordinary favor and civility on the account of his uncle the lord Harrington, who had bin her governor; but particularly for the sake of his own merit. The prince elector also courted him into his service, ingag’d him to attend him in a journy he made to the court of Denmark, and, after his return from travelling, committed the chief management of all his affairs in England to his care. Nor were the young princesses less delighted with his company, his conversation being always extremely pleasant, as well as learned and polite; to which good qualitys those unfortunat ladies were far from being strangers, as appears by the letters of the great philosopher Cartesius, and by the other writers of those times.

4. Tho he found many charms inviting his longer stay in this place, yet none were strong enough to keep him from pursuing his main design of travelling; and therfore he went next thro Flanders into France, where having perfected himself in the language, seen what deserv’d his curiosity, and made such remarks on their government as will best appear in his works, he remov’d thence into Italy. It happen’d to be then (as it is now) the year of jubilee. He always us’d to admire the great dexterity wherwith the Popish clergy could maintain their severe government over so great a part of the world, and that men otherwise reasonable enough should be inchanted out of their senses, as well as cheated out of their mony, by these ridiculous tricks of religious pageantry. Except the small respect he shew’d to the miracles they daily told him were perform’d in their churches, he did in all other things behave himself very prudently and inoffensively. But going on a Candlemas day with several other Protestants, to see the Pope perform the ceremony of consecrating wax lights; and perceiving that none could obtain any of those torches, except such as kist the Pope’s toe (which he expos’d to ’em for that purpose) tho he had a great mind to one of the lights, yet he would not accept it on so hard a condition. The rest of his companions were not so scrupulous, and after their return complain’d of his squeamishness to the king; who telling him he might have don [xiii] it only as a respect to a temporal prince, he presently reply’d, that since he had the honor to kiss his majesty’s hand, he thought it beneath him to kiss any other prince’s foot. The king was pleased with his answer, and did afterwards admit him to be one of his privy chamber extraordinary, in which quality he attended him in his first expedition against the Scots.

5. He prefer’d Venice to all other places in Italy, as he did its government to all those of the whole world, it being in his opinion immutable by any external or internal causes, and to finish only with mankind; of which assertion you may find various proofs alleg’d in his works. Here he furnish’d himself with a collection of all the valuable books in the Italian language, especially treating of politics, and contracted acquaintance with every one of whom he might receive any benefit by instruction or otherwise.

6. After having thus seen Italy, France, the Low Countrys, Denmark, and som parts of Germany, he return’d home into England, to the great joy of all his friends and acquaintance. But he was in a special manner the darling of his relations, of whom he acknowleg’d to receive reciprocal satisfaction. His brothers and sisters were now pretty well grown, which made it his next care so to provide for each of ’em as might render ’em independent of others, and easy to themselves. His brother William he bred to be a merchant, in which calling he became a considerable man; he was a good architect, and was so much notic’d for his ingenious contrivances, that he was receiv’d a fellow of the royal society. How his other brothers were dispos’d, we mention’d in the beginning of this discourse. He took all the care of a parent in the education of his sisters, and wou’d himself make large discourses to ’em concerning the reverence that was due to Almighty God; the benevolence they were oblig’d to shew all mankind; how they ought to furnish their minds with knowlege by reading of useful books, and to shew the goodness of their disposition by a constant practice of virtue: in a word, he taught ’em the true rules of humanity and decency, always inculcating to ’em, that good manners did not so much consist in a fashionable carriage (which ought not to be neglected) as in becoming words and actions, an obliging address, and a modest behavior. He treated his mother in law as if she were his own, and made no distinction between her children and the rest of his brothers and sisters; which good example had such effects on ’em all, that no family has bin more remarkable for their mutual friendship.

7. He was of a very liberal and compassionate nature, nor could he indure to see a friend want any thing he might spare; and when the relief that was necessary exceded the bounds of his estate, he persuaded his sisters not only to contribute themselves, but likewise to go about to the rest of their relations to complete what was wanting. And if at any time they alleg’d that this bounty had been thrown away on ungrateful persons, he would answer with a smile, that he saw they were mercenary, and that they plainly sold their gifts, since they expected so great a return as gratitude.

8. His natural inclinations to study kept him from seeking after any public imployments. But in the year 1646, attending out of curiosity the commissioners appointed by parlament to bring King Charles the First from Newcastle nearer to London, he was by som of ’em nam’d to wait on his majesty, as a person known to him before, and ingag’d to no party or faction. The king approv’d the proposal, yet our author would never presume to come into his presence except in public, [xiv] till he was particularly commanded by the king; and that he, with Thomas Herbert (created a baronet after the restoration of the monarchy) were made grooms of the bedchamber at Holmby, together with James Maxwell and Patrick Maule (afterwards earl of Penmoore in Scotland) which two only remain’d of his old servants in that station.

9. He had the good luck to grow very acceptable to the king, who much convers’d with him about books and foren countrys. In his sister’s papers I find it exprest, that at the king’s command he translated into English Dr. Sanderson’s book concerning the obligation of oaths: but Anthony Wood says it was the king’s own doing, and that he shew’d it at different times to Harrington, Herbert, Dr. Juxon, Dr. Hammond, and Dr. Sheldon, for their approbation. However that be, ’tis certain he serv’d his master with untainted fidelity, without doing any thing inconsistent with the liberty of his country; and that he made use of his interest with his friends in parlament to have matters accommodated for the satisfaction of all partys. During the treaty in the Isle of Wight, he frequently warn’d the divines of his acquaintance to take heed how far they prest the king to insist upon any thing which, however it concern’d their dignity, was no essential point of religion; and that such matters driven too far wou’d infallibly ruin all the indeavours us’d for a peace; which prophecy was prov’d too true by the event. His majesty lov’d his company, says Anthony Wood, and, finding him to be an ingenious man, chose rather to converse with him than with others of his chamber: they had often discourses concerning government; but when they happen’d to talk of a commonwealth, the king seem’d not to indure it. Here I know not which most to commend, the king for trusting a man of republican principles, or Harrington for owning his principles while he serv’d a king.

10. After the king was remov’d out of the Isle of Wight to Hurstcastle in Hampshire, Harrington was forcibly turn’d out of service, because he vindicated som of his majesty’s arguments against the parlament commissioners at Newport, and thought his concessions not so unsatisfactory as did som others. As they were taking the king to Windsor, he beg’d admittance to the boot of the coach, that he might bid his master farewel; which being granted, and he preparing to kneel, the king took him by the hand, and pull’d him in to him. He was for three or four days permitted to stay: but because he would not take an oath against assisting or concealing the king’s escape, he was not only discharg’d from his office, but also for som time detain’d in custody, till major-general Ireton obtain’d his liberty. He afterwards found means to see the king at St. James’s, and accompany’d him on the scaffold, where, or a little before, he receiv’d a token of his majesty’s affection.

11. After the king’s death he was observ’d to keep much in his library, and more retir’d than usually, which was by his friends a long time attributed to melancholy or discontent. At length when they weary’d him with their importunitys to change this sort of life, he thought fit to shew ’em at the same time their mistake and a copy of his Oceana, which he was privatly writing all that while: telling ’em withal, that ever since he began to examin things seriously, he had principally addicted himself to the study of civil government, as being of the highest importance to the peace and felicity of mankind; and that he succeded at least to his own satisfaction, being now convinc’d that no government is of so accidental or arbitrary an institution as people are wont to imagin, there being in societys natural causes producing their necessary effects, as well as in the earth or the air. Hence he [xv] frequently argu’d, that the troubles of his time were not to be wholly attributed to wilfulness or faction, neither to the misgovernment of the prince, nor the stubborness of the people; but to change in the balance of property, which ever since Henry the Seventh’s time was daily falling into the scale of the commons from that of the king and the lords, as in his book he evidently demonstrats and explains. Not that hereby he approv’d either the breaches which the king had made on the laws, or excus’d the severity which som of the subjects exercis’d on the king; but to shew that as long as the causes of these disorder’s remain’d, so long would the like effects unavoidably follow: while on the one hand a king would be always indeavoring to govern according to the example of his predecessors when the best part of the national property was in their own hands, and consequently the greatest command of mony and men, as one of a thousand pounds a year can entertain more servants, or influence more tenants than another that has but one hundred, out of which he cannot allow one valet; and on the other hand he said, the people would be sure to struggle for preserving the property wherof they were in possession, never failing to obtain more privileges, and to inlarge the basis of their liberty, as often as they met with any success (which they generally did) in quarrels of this kind. His chief aim therfore was to find out a method of preventing such distempers, or to apply the best remedys when they happen’d to break out. But as long as the balance remain’d in this unequal state, he affirm’d that no king whatsoever could keep himself easy, let him never so much indeavor to please his people; and that though a good king might manage affairs tolerably well during his life, yet this did not prove the government to be good, since under a less prudent prince it would fall to pieces again, while the orders of a well constituted state make wicked men virtuous, and fools to act wisely.

12. That empire follows the balance of property, whether lodg’d in one, in a few, or in many hands, he was the first that ever made out; and is a noble discovery, wherof the honor solely belongs to him, as much as those of the circulation of the blood, of printing, of guns, of the compass, or of optic glasses, to the several authors. ’Tis incredible to think what gross and numberless errors were committed by all the writers before him, even by the best of them, for want of understanding this plain truth, which is the foundation of all politics. He no sooner discours’d publicly of this new doctrin, being a man of universal acquaintance, but it ingag’d all sorts of people to busy themselves about it as they were variously affected. Som, because they understood him, despis’d it, alleging it was plain to every man’s capacity, as if his highest merit did not consist in making it so. Others, and those in number the fewest, disputed with him about it, merely to be better inform’d; with which he was well pleas’d, as reckoning a pertinent objection of greater advantage to the discovery of truth (which was his aim) than a complaisant applause or approbation. But a third sort, of which there never wants in all places a numerous company, did out of pure envy strive all they could to lessen or defame him; and one of ’em (since they could not find any precedent writer out of whose works they might make him a plagiary) did endeavor, after a very singular manner, to rob him of the glory of this invention: for our author having friendly lent him a part of his papers, he publish’d a small piece to the same purpose, intitled, A letter from an officer of the army in Ireland, &c. Major Wildman was then reputed the author by som, and Henry Nevil by others; which latter, by reason of this thing, and his great intimacy with Harrington, was by his detractors reported to be the [xvi] author of his works, or that at least he had a principal hand in composing of them. Notwithstanding which provocations, so true was he to the friendship he profest to Nevil and Wildman, that he avoided all harsh expressions or public censures on this occasion, contenting himself with the justice which the world was soon oblig’d to yield to him by reason of his other writings, where no such clubbing of brains could be reasonably suspected.

13. But the publication of his book met with greater difficultys from the opposition of the several partys then set against one another, and all against him; but none more than som of those who pretended to be for a commonwealth, which was the specious name under which they cover’d the rankest tyranny of Oliver Cromwel, while Harrington, like Paul at Athens, indeavor’d to make known to the people what they ignorantly ador’d. By shewing that a commonwealth was a government of laws, and not of the sword, he could not but detect the violent administration of the protector by his bashaws, intendants, or majors general, which created him no small danger: while the cavaliers on the other side tax’d him with ingratitude to the memory of the late king, and prefer’d the monarchy even of a usurper to the best order’d commonwealth. To these he answer’d, that it was enough for him to forbear publishing his sentiments during that king’s life; but the monarchy being now quite dissolv’d, and the nation in a state of anarchy, or (what was worse) groaning under a horrid usurpation, he was not only at liberty, but even oblig’d as a good citizen to offer a helping hand to his countrymen, and to shew ’em such a model of government as he thought most conducing to their tranquillity, wealth and power: that the cavaliers ought of all people to be best pleas’d with him, since if his model succeded, they were sure to enjoy equal privileges with others, and so be deliver’d from their present oppression; for in a well-constituted commonwealth there can be no distinction of partys, the passage to preferment is open to merit in all persons, and no honest man can be uneasy: but that if the prince should happen to be restor’d, his doctrin of the balance would be a light to shew him what and with whom he had to do, and so either to amend or avoid the miscarriages of his father; since all that is said of this doctrin may as well be accommodated to a monarchy regulated by laws, as to a democracy or more popular form of a commonwealth. He us’d to add on such occasions another reason of writing this model, which was, That if it should ever be the fate of this nation to be, like Italy of old, overrun by any barbarous people, or to have its government and records destroy’d by the rage of som merciless conqueror, they might not be then left to their own invention in framing a new government; for few people can be expected to succede so happily as the Venetians have don in such a case.

14. In the mean time it was known to som of the courtiers, that the book was a printing; whereupon, after hunting it from one press to another, they seiz’d their prey at last, and convey’d it to Whitehall. All the sollicitations he could make were not able to relieve his papers, till he remember’d that Oliver’s favorit daughter, the lady Claypole, acted the part of a princess very naturally, obliging all persons with her civility, and frequently interceding for the unhappy. To this lady, tho an absolute stranger to him, he thought fit to make his application; and being led into her antichamber, he sent in his name, with his humble request that she would admit him to her presence. While he attended, som of her women coming into the room were follow’d by her little daughter about three years old, [xvii] who staid behind them. He entertain’d the child so divertingly, that she suffer’d him to take her up in his arms till her mother came; whereupon he stepping towards her, and setting the child down at her feet, said, Madam, ’tis well you are com at this nick of time, or I had certainly stolen this pretty little lady. Stolen her, reply’d the mother! pray, what to do with her? for she is yet too young to becom your mistress. Madam, said he, tho her charms assure her of a more considerable conquest, yet I must confess it is not love but revenge that promted me to commit this theft. Lord, answer’d the lady again, what injury have I don you that you should steal my child? none at all, reply’d he, but that you might be induc’d to prevail with your father to do me justice, by restoring my child that he has stolen. But she urging it was impossible, because her father had children enough of his own; he told her at last it was the issue of his brain which was misrepresented to the protector, and taken out of the press by his order. She immediately promis’d to procure it for him, if it contain’d nothing prejudicial to her father’s government; and he assur’d her it was only a kind of a political romance, so far from any treason against her father, that he hop’d she would acquaint him that he design’d to dedicat it to him, and promis’d that she her self should be presented with one of the first copys. The lady was so well pleas’d with his manner of address, that he had his book speedily restor’d to him; and he did accordingly inscribe it to Oliver Cromwel, who, after the perusal of it, said, the gentleman had like to trapan him out of his power, but that what he got by the sword he would not quit for a little paper shot: adding in his usual cant, that he approv’d the government of a single person as little as any of ’em, but that he was forc’d to take upon him the office of a high constable, to preserve the peace among the several partys in the nation, since he saw that being left to themselves, they would never agree to any certain form of government, and would only spend their whole power in defeating the designs, or destroying the persons of one another.

15. But nothing in the world could better discover Cromwel’s dissimulation than this speech, since Harrington had demonstrated in his book, that no commonwealth could be so easily or perfectly establish’d as one by a sole legislator, it being in his power (if he were a man of good invention himself, or had a good model propos’d to him by others) to set up a government in the whole piece at once, and in perfection; but an assembly, being of better judgment than invention, generally make patching work in forming a government, and are whole ages about that which is seldom or never brought by ’em to any perfection; but is commonly ruin’d by the way, leaving the noblest attemts under reproach, and the authors of ’em expos’d to the greatest dangers while they live, and to a certain infamy when dead. Wherfore the wisest assemblys, in mending or making a government, have pitch’d upon a sole legislator, whose model they could rightly approve, tho not so well digest; as musicians can play in consort, and judg of an air that is laid before them, tho to invent a part of music they could never agree, nor succede so happily as one person. If Cromwel therfore had meant as he spoke, no man had ever such an opportunity of reforming what was amiss in the old government, or setting up one wholly new, either according to the plan of Oceana, or any other. This would have made him indeed a hero superior in lasting fame to Solon, Lycurgus, Zaleucus, and Charondas; and render his glory far more resplendent, his security greater, and his renown more durable than all the pomp of his ill acquir’d greatness could afford: whereas on the contrary he liv’d in continual fears of those [xviii] he had inslav’d, dy’d abhor’d as a monstrous betrayer of those libertys with which he was intrusted by his country, and his posterity not possessing a foot of what for their only sakes he was generally thought to usurp But this last is a mistaken notion, for som of the most notorious tyrants liv’d and dy’d without any hopes of children; which is a good reason why no mortal ought to be trusted with too much power on that score. Lycurgus and Andrew Doria, who, when it was in their power to continue princes, chose rather to be the founders of their countrys liberty, will be celebrated for their virtue thro the course of all ages, and their very names convey the highest ideas of Godlike generosity; while Julius Cæsar, Oliver Cromwel, and such others as at any time inslav’d their fellow citizens, will be for ever remember’d with detestation, and cited as the most execrable examples of the vilest treachery and ingratitude. It is only a refin’d and excellent genius, a noble soul ambitious of solid praise, a sincere lover of virtue and the good of all mankind, that is capable of executing so glorious an undertaking as making a people free. ’Tis my fix’d opinion, that if the protector’s mind had the least tincture of true greatness, he could not be proof against the incomparable rewards propos’d by Harrington in the corollary of his Oceana; as no prince truly generous, whether with or without heirs, is able to resist their charms, provided he has opportunity to advance the happiness of his people. ’Twas this disposition that brought the prince of Orange to head us when we lately contended for our libesty; to this we ow those inestimable laws we have obtain’d, since out of a grateful confidence we made him our king; and how great things, or after what manner, we may expect from him in time to com, is as hard to be truly conceiv’d as worthily express’d.

16. I shall now give som account of the book itself, intitl’d by the author, The Commonwealth of Oceana, a name by which he design’d England, as being the noblest iland of the Northern ocean. But before I procede further, I must explain som other words occurring in this book, which is written after the manner of a romance, in imitation of Plato’s Atlantic story, and is a method ordinarily follow’d by lawgivers.

| Adoxus | King JOHN. |

| Alma | The palace of St. JAMES. |

| Convallium | Hamton Court. |

| Coraunus | HENRY VIII. |

| Dicotome | RICHARD II. |

| Emporium | London. |

| Halcionia | The Thames. |

| Halo | Whitehall. |

| Hemisua | The river Trent. |

| Hiera | Westminster. |

| Leviathan | HOBBES. |

| Marpesia | Scotland. |

| Morpheus | JAMES I. |

| Mount Celia | Windsor. |

| Neustrians | Normans. |

| Olphaus Megaletor | OLIVER CROMWEL. |

| Panopæa | Ireland. |

[xix]

| Pantheon | Westminster Hall. |

| Panurgus | HENRY VII. |

| Parthenia | Queen ELIZABETH. |

| Scandians | Danes. |

| Teutons | Saxons. |

| Turbo | WILLIAM the Conqueror. |

| Verulamius | Lord Chancellor BACON. |

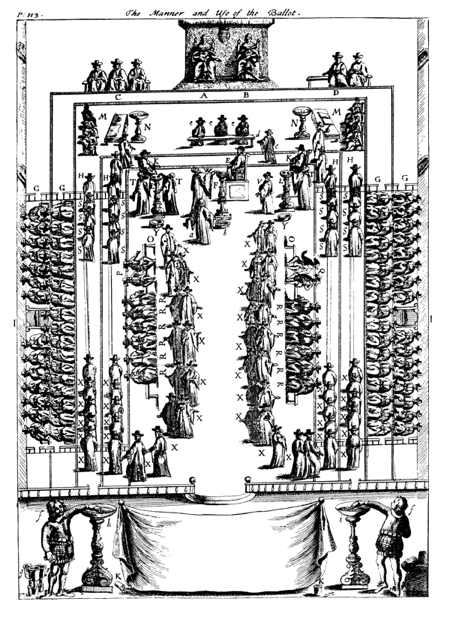

17. The book consists of Preliminarys divided into two parts, and a third section called the Council of Legislators; then follows the Model of the Commonwealth, or the body of the book; and lastly coms the Corollary or Conclusion. The preliminary discourses contain the principles, generation, and effects of all governments, whether monarchical, aristocratical, or popular, and their several corruptions, as tyranny, oligarchy, and anarchy, with all the good or bad mixtures that naturally result from them. But the first part dos in a more particular manner treat of antient prudence, or that genius of government which most prevail’d in the world till the time of Julius Cæsar. None can consult a more certain oracle that would conceive the nature of foren or domestic empire; the balance of land or mony; arms or contracts; magistracy and judicatures; agrarian laws; elections by the ballot; rotation of officers, with a great many such heads, especially the inconveniences and preeminences of each kind of government, or the true comparison of ’em all together. These subjects have bin generally treated distinctly, and every one of them seems to require a volum; yet I am of opinion that in this short discourse there is a more full and clearer account of them, than can be easily found elsewhere: at least I must own to have receiv’d greater satisfaction here than in all my reading before, and the same thing has bin frankly own’d to me by others.

18. The second part of the Preliminarys treats of modern prudence, or that genius of government which has most obtain’d in the world since the expiration of the Roman liberty, particularly the Gothic constitution, beginning with the inundation of the barbarous northern nations over the Roman empire. In this discourse there is a very clear account of the English government under the Romans, Saxons, Danes, and Normans, till the foundations of it were cunningly undermin’d by Henry VII. terribly shaken by Henry VIII. and utterly ruin’d under Charles I. Here he must read, who in a little compass would completely understand the antient feuds and tenures, the original and degrees of our nobility, with the inferior orders of the rest of the people: under the Saxons, what was meant by ealdorman, or earls; king’s thane; middle thane or vavasors; their shiremoots, sherifs, and viscounts; their halymoots, weidenagemoots, and such others. Here likewise one may learn to understand the baronage of the Normans, as the barons by their possessions, by writ, or by letters patent; with many other particulars which give an insight into the springs and management of the barons wars, so frequent and famous in our annals. The rest of this discourse is spent in shewing the natural causes of the dissolution of the Norman monarchy under Charles the First, and the generation of the commonwealth, or rather the anarchy that succeded.

19. Next follows the Council of Legislators: for Harrington being about to give the most perfect model of government, he made himself master of all the antient and modern politicians, that he might as well imitat whatever was excellent or practicable in them, as his care was to avoid all things which were impracticable [xx] or inconvenient. These were the justest measures that could possibly be taken by any body, whether he design’d to be rightly inform’d, and sufficiently furnish’d with the best materials; or whether he would have his model meet with an easy reception: for since his own sentiments (tho’ never so true) were sure to be rejected as privat speculations or impracticable chimeras, this was the readiest way to make ’em pass currently, as both authoriz’d by the wisest men in all nations, and as what in all times and places had bin practis’d with success. To this end therefore he introduces, under feign’d names, nine legislators, who perfectly understood the several governments, they were appointed to represent. The province of the first was the commonwealth of Israel; that of the second, Athens; of the third, Sparta; of the fourth, Carthage; of the fifth, the Achæans, Ætolians, and Lycians; of the sixth, Rome; of the seventh, Venice; of the eighth, Switzerland; and of the ninth, Holland. Out of the excellencys of all these, supply’d with the fruits of his own invention, he fram’d the model of his Oceana; and indeed he shews himself in that work so throly vers’d in their several historys and constitutions, that to any man who would rightly understand them, I could not easily recommend a more proper teacher: for here they are dissected and laid open to all capacitys, their perfections applauded, their inconveniencys expos’d, and parallels frequently made between ’em no less entertaining than usual. Nor are the antient and modern Eastern or European monarchys forgot, but exhibited with all their advantages and corruptions, without the least dissimulation or partiality.

20. As for the model, I shall say nothing of it in particular, as well because I would not forestal the pleasure of the reader, as by reason an abridgment of it is once or twice made by himself, and inserted among his works. The method he observes is to lay down his orders or laws in so many positive propositions, to each of which he subjoins an explanatory discourse; and if there be occasion, adds a speech suppos’d to be deliver’d by the lord Archon, or som of the legislators. These speeches are extraordinary fine, contain a world of good learning and observation, and are perpetual commentarys on his laws. In the Corollary, which is the conclusion of the whole work, he shews how the last hand was put to his commonwealth; which we must not imagin to treat only of the form of the senat and affemblys of the people, or the manner of waging war and governing in peace. It contains besides, the disciplin of a national religion, and the security of a liberty of conscience: a form of government for Scotland, for Ireland, and the other provinces of the commonwealth; governments for London and Westminster, proportionably to which the other corporations of the nation are to be model’d; directions for the incouraging of trade; laws for regulating academys; and most excellent rules for the education of our youth, as well to the wars or the sea, to manufactures or husbandry, as to law, physic, or divinity, and chiefly to the breeding and true figure of accomplish’d gentlemen: there are admirable orders for reforming the stage; the number, choice and business of the officers of state and the revenue, with all sorts of officers; and an exact account both of their salarys, and the ordinary yearly charge of the whole commonwealth, which for two rarely consistent things, the grandeur of its state, and the frugal management of its revenues, excedes all the governments that ever were. I ought not to omit telling here, that this model gives a full answer to those who imagin that there can be no distinctions, or degrees, neither nobility nor gentry in a democracy, being led into this mistake, because they ignorantly think all commonwealths to be constituted alike; when, [xxi] if they were but never so little vers’d in history, they might know that no order of men now in the world can com near the figure that was made by the noblemen and gentlemen of the Roman state: nor in this respect dos the commonwealth of Oceana com any thing behind them; for, as Harrington says very truly, an army may as well consist of soldiers without officers, or of officers without soldiers, as a commonwealth (especially such an one as is capable of greatness) consist of a people without a gentry, or of a gentry without a people. So much may suffice for understanding the scope of this book: I shall only add, that none ought to be offended with a few odd terms in it, such as the prime magnitude, the pillar of Nilus, the galaxy, and the tropic of magistrats, since the author explains what he means by ’em, and that any other may call ’em by what more significative names he pleases; for t’ e things themselves are absolutely necessary.

21. No sooner did this treatise appear in public, but it was greedily bought up, and becom the subject of all men’s discourse. The first that made exceptions to it was Dr. Henry Ferne, afterwards bishop of Chester. The lady Ashton presented him with one of the books, and desir’d his opinion of it, which he quickly sent in such a manner as shew’d he did not approve of the doctrin, tho he treated the person and his learning with due respect. To this letter a reply was made, and som querys sent along with it by Harrington, to every one of which a distinct answer was return’d by the doctor; which being again confuted by Harrington, he publish’d the whole in the year 1656, under the title of Pian Piano, or an Intercourse between H. Ferne doctor in divinity, and James Harrington, Esq; upon occasion of the doctor’s censure of the commonwealth of Oceana. ’Tis a treatise of little importance, and contains nothing but what he has much better discours’d in his answers to other antagonists, which is the reason that I give the reader no more trouble about it.

22. The next that wrote against Oceana was Matthew Wren, eldest son to the bishop of Ely. His book was intitl’d Considerations, and restrain’d only to the first part of the preliminarys. To this our author publish’d an answer in the first book of his Prerogative of Popular Government, where he inlarges, explains, and vindicats his assertions. How inequal this combat was, and after what manner he treated his adversary, I leave the reader to judg; only minding him that as Wren was one of the virtuosi who met at Dr. Wilkins’s (the seminary of the now royal society) Harrington jokingly said, That they had an excellent faculty of magnifying a louse, and diminishing a commonwealth. But the subjects he handles on this occasion are very curious, and reduc’d to the twelve following questions:

(1) Whether prudence (or the politics) be well distinguish’d into antient and modern?

(2.) Whether a commonwealth be rightly defin’d to be a government of laws and not of men; and monarchy to be a government of som men or a few men, and not of laws?

(3.) Whether the balance of dominion in land be the natural cause of empire?

(4.) Whether the balance of empire be well divided into national and provincial? and whether these two, or any nations that are of a distinct balance, coming to depend on one and the same head, such a mixture creates a new balance?

(5.) Whether there be any common right or interest of mankind distinct from the interest of the parts taken severally? and how by the orders of a commonwealth this may best be distinguish’d from privat interest?

[xxii]

(6.) Whether the senatusconsulta, or decrees of the Roman senat, had the power of laws?

(7.) Whether the ten commandments, propos’d by God or Moses, were voted and past into laws by the people of Israel?

(8.) Whether a commonwealth, coming up to the perfection of the kind, coms not up to the perfection of government, and has no flaw in it? that is, whether the best commonwealth be not the best government?

(9.) Whether monarchy, coming up to the perfection of the kind, coms not short of the perfection of government, and has not som flaw in it? that is, whether the best monarchy be not the worst government? Under this head are also explain’d the balance of France, the original of a landed clergy, arms, and their several kinds.

(10.) Whether any commonwealth, that was not first broken or divided by it self, was ever conquer’d by any monarch? where he shews that none ever were, and that the greatest monarchys have bin broken by very small commonwealths.

(11.) Whether there be not an agrarian, or som law or laws to supply the defects of it, in every commonwealth? Whether the agrarian, as it is stated in Oceana, be not equally satisfactory to all interests or partys?

(12.) Whether a rotation, or courses and turns, be necessary to a well-order’d commonwealth? In which is contain’d the parembole or courses of Israel before the captivity, together with an epitome of the commonwealth of Athens, as also another of the commonwealth of Venice.

23. The second book of the Prerogative of Popular Government chiefly concerns ordination in the Christian church, and the orders of the commonwealth of Israel, against the opinions of Dr. Hammond, Dr. Seaman, and the authors they follow. His dispute with these learned persons (the one of the Episcopal, and the other of the Presbyterian communion) is comprehended in five chapters.

(1.) The first, explaining the words chirotonia and chirothesia, paraphrastically relates the story of the perambulation made by the apostles Paul and Barnabas thro the citys of Lycaonia, Pisidia, &c.

(2.) The second shews that those citys, or most of ’em, were at the time of this perambulation under popular government; in which is also contain’d the whole administration of a Roman province.

(3.) The third shews the deduction of the chirotonia, or holding up of hands, from popular government, and that the original of ordination is from this custom; in which is also contain’d the institution of the sanhedrim or senat of Israel by Moses, and of that of Rome by Romulus.

(4.) The fourth shews the deduction of the chirothesia, or the laying on of hands, from monarchical or aristocratical government, and so the second way of ordination proceeds from this custom: here is also declar’d how the commonwealth of the Jews stood after the captivity.

(5.) The fifth debates whether the chirotonia us’d in the citys mention’d was (as is pretended by Dr. Hammond, Dr. Seaman, and the authors they follow) the same with the chirothesia, or a far different thing. In which are contain’d the divers kinds of church government introduc’d and exercis’d in the age of the apostles. By these heads we may perceive that a great deal of useful learning is contain’d in this book; and questionless he makes those subjects more plain and intelligible than any writer I ever yet consulted.

[xxiii]

24. Against Oceana chiefly did Richard Baxter write his Holy Commonwealth, of which our author made so slight, that he vouchsaf’d no other answer to it but half a sheet of cant and ridicule. It dos not appear that he rail’d at all the ministers as a parcel of fools and knaves. But the rest of Baxter’s complaint seems better grounded, as that Harrington maintain’d neither he nor any ministers understood at all what polity was, but prated against they knew not what, &c. This made him publish his Holy Commonwealth in answer to Harrington’s Heathenish Commonwealth; in which, adds he, I plead the cause of monarchy as better than democracy or aristocracy; an odd way of modelling a commonwealth. And yet the royalists were so far from thinking his book for their service, that in the year 1683 it was by a decree of the university of Oxford condemn’d to be publicly burnt; which sentence was accordingly executed upon it, in company with some of the books of Hobbes, Milton, and others; wheras no censure past on Harrington’s Oceana, or the rest of his works. As for divines meddling with politics, he has in the former part of the preliminarys to Oceana deliver’d his opinion, That there is somthing first in the making of a commonwealth, then in the governing of it, and last of all in the leading of its armys, which (tho there be great divines, great lawyers, great men in all professions) seems to be peculiar only to the genius of a gentleman: for it is plain in the universal series of story, that if any man founded a commonwealth, he was first a gentleman; the truth of which assertion he proves from Moses downwards.

25. Being much importun’d from all hands to publish an abridgment of his Oceana, he consented at length; and so, in the year 1659, was printed his Art of Lawgiving (or of legislation) in three books. The first, which treats of the foundation and superstructures of all kinds of government, is an abstract of his preliminarys to the Oceana: and the third book, shewing a model of popular government fitted to the present state or balance of this nation, is an exact epitome of his Oceana, with short discourses explaining the propositions. By the way, the pamphlet called the Rota is nothing else but these propositions without the discourses, and therfore, to avoid a needless repetition, not printed among his works. The second book between these two, is a full account of the commonwealth of Israel, with all the variations it underwent. Without this book it is plainly impossible to understand that admirable government concerning which no author wrote common sense before Harrington, who was persuaded to complete this treatise by such as observ’d his judicious remarks on the same subject in his other writings. To the Art of Lawgiving is annex’d a small dissertation, or a Word concerning a House of Peers, which to abridg were to transcribe.

26. In the same year, 1659, Wren coms out with another book call’d Monarchy asserted, in vindication of his Considerations. If he could not press hard on our author’s reasonings, he was resolv’d to overbear him with impertinence and calumny, treating him neither with the respect due to a gentleman, nor the fair dealing becoming an ingenuous adversary, but on the contrary with the utmost chicanery and insolence. The least thing to be admir’d is, that he would needs make the university a party against him, and bring the heavy weight of the church’s displeasure on his shoulders: for as corrupt ministers stile themselves the government, by which artifice they oblige better men to suppress their complaints, for fear of having their loyalty suspected; so every ignorant pedant that affronts a gentleman, is presently a learned university; or if he is but in deacon’s orders, he’s forthwith transform’d into the catholic church, and it becoms sacrilege to touch him. But [xxiv] as great bodys no less than privat persons, grow wiser by experience, and com to a clearer discernment of their true interest; so I believe that neither the church no universitys will be now so ready to espouse the quarrels of those, who, under pretence of serving them, ingage in disputes they no ways understand, wherby all the discredit redounds to their patrons, themselves being too mean to suffer any diminution of honor. Harrington was not likewise less blamable in being provok’d to such a degree by this pitiful libel, as made him forget his natural character of gravity and greatness of mind. Were not the best of men subject to their peculiar weaknesses, he had never written such a farce as his Politicaster, or Comical Discourse in answer to Mr. Wren. It relates little or nothing to the argument, which was not so much amiss, considering the ignorance of his antagonist: but it is of so very small merit, that I would not insert it among his other works, as a piece not capable to instruct or please any man now alive. I have not omitted his Answer to Dr. Stubbe concerning a select senat, as being so little worth; but as being only a repetition of what he has much better and more amply treated in some of his other pieces. Now we must note, that upon the first appearance of his Oceana this Stubbe was so great an admirer of him, that, in his preface to the Good Old Cause, he says he would inlarge in his praise, did he not think himself too inconsiderable to add any thing to those applauses which the understanding part of the world must bestow upon him, and which, tho eloquence should turn panegyrist, he not only merits but transcends.