Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume III: The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole (1894, 1909)

|

|

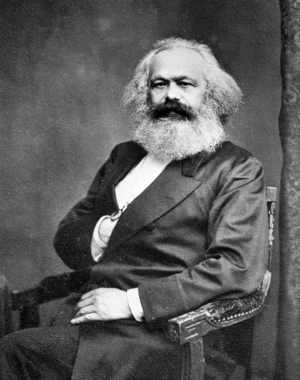

| Karl Marx (1818-1883) |

Source

Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume III: The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole, by Karl Marx. Ed. Frederick Engels. Trans. from the 1st German edition by Ernest Untermann (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr and Co. Cooperative, 1909).

See also:

- vol. 1 in HTML and facs. PDF and in German Band I in HTML and facs. PDF

- vol. 2 in HTML and facs. PDF and in German Band II in HTML and facs. PDF

- vol. 3 in HTML and facs. PDF and in German Band IIIa in HTML and facs. PDF Band IIIb in HTML and facs. PDF

Table of Contents:

- PREFACE by Frederick Engels

- VOLUME III. THE PROCESS OF CAPITALIST PRODUCTION AS A WHOLE.

- PART I.: THE CONVERSION OF SURPLUS-VALUE INTO

PROFIT AND OF THE RATE OF SURPLUS-VALUE INTO

THE RATE OF PROFIT.

- CHAPTER I.: COST PRICE AND PROFIT.

- CHAPTER II.: THE RATE OF PROFIT.

- CHAPTER III.: THE RELATION OF THE RATE OF PROFIT TO THE RATE OF SURPLUS-VALUE.

- CHAPTER IV.: THE EFFECT OF THE TURN-OVER ON THE RATE OF PROFIT.

- CHAPTER V.: ECONOMIES IN THE EMPLOYMENT OF CONSTANT CAPITAL.

- CHAPTER VI.: THE EFFECT OF FLUCTUATIONS IN PRICE.

- CHAPTER VII.: ADDITIONAL REMARKS.

- PART II.: CONVERSION OF PROFIT INTO AVERAGE PROFIT.

- CHAPTER VIII.: DIFFERENT COMPOSITION OF CAPITALS IN DIFFERENT LINES OF PRODUCTION AND RESULTING DIFFERENCES IN THE RATES OF PROFIT.

- CHAPTER IX.: FORMATION OF A GENERAL RATE OF PROFIT (AVERAGE RATE OF PROFIT) AND TRANSFORMATION OF THE VALUES OF COMMODITIES INTO PRICES OF PRODUCTION

- CHAPTER X.: COMPENSATION OF THE AVERAGE RATE OF PROFIT BY COMPETITION. MARKET PRICES AND MARKET VALUES. SURPLUS-PROFIT.

- CHAPTER XI.: EFFECTS OF GENERAL FLUCTUATIONS OF WAGES ON PRICES OF PRODUCTION.

- CHAPTER XII.: SOME AFTER REMARKS.

- PART III.: THE LAW OF THE FALLING TENDENCY OF THE RATE OF PROFIT.

- PART IV.: TRANSFORMATION OF COMMODITY-CAPITAL AND MONEY-CAPITAL INTO COMMERCIAL CAPITAL AND FINANCIAL CAPITAL (MERCHANT'S CAPITAL).

- CHAPTER XVI.: COMMERCIAL CAPITAL.

- CHAPTER XVII.: COMMERCIAL PROFIT.

- CHAPTER XVIII.: THE TURN-OVER OF MERCHANT'S CAPITAL. THE PRICES.

- CHAPTER XIX.: FINANCIAL CAPITAL.

- CHAPTER XX.: HISTORICAL DATA CONCERNING MERCHANTS' CAPITAL.

- PART V.: DIVISION OF PROFIT INTO INTEREST AND PROFITS OF ENTERPRISE. THE INTEREST-BEARING CAPITAL.

- CHAPTER XXI.: THE INTEREST-BEARING CAPITAL.

- CHAPTER XXII.: DIVISION OF PROFIT. RATE OF INTEREST. NATURAL RATE OF INTEREST.

- CHAPTER XXIII.: INTEREST AND PROFIT OF ENTERPRISE.

- CHAPTER XXIV.: EXTERNALISATION OF THE RELATIONS OF CAPITAL IN THE FORM OF INTEREST-BEARING CAPITAL.

- CHAPTER XXV.: CREDIT AND FICTITIOUS CAPITAL.

- CHAPTER XXVI.: ACCUMULATION OF MONEY-CAPITAL. ITS INFLUENCE ON THE RATE OF INTEREST.

- CHAPTER XXVII.: THE ROLE OF CREDIT IN CAPITALIST PRODUCTION.

- CHAPTER XXVIII.: THE MEDIUM OF CIRCULATION (CURRENCY) AND CAPITAL. TOOKE'S AND FULLARTON'S CONCEPTION.

- CHAPTER XXIX.: THE COMPOSITION OF BANKING CAPITAL.

- CHAPTER XXX.: MONEY-CAPITAL AND ACTUAL CAPITAL, I.

- CHAPTER XXXI.: MONEY-CAPITAL AND ACTUAL CAPITAL. II. (Continued.)

- CHAPTER XXXII.: MONEY-CAPITAL AND ACTUAL CAPITAL. III. (Concluded.)

- CHAPTER XXXIII.: THE CURRENCY UNDER THE CREDIT SYSTEM.

- CHAPTER XXXIV.: THE CURRENCY PRINCIPLE AND THE ENGLISH BANK LAWS OF 1844.

- CHAPTER XXXV.: PRECIOUS METALS AND RATES OF EXCHANGE.

- CHAPTER XXXVI.: PRECAPITALIST CONDITIONS.

- PART VI.: TRANSFORMATION OF SURPLUS PROFIT INTO GROUND-RENT.

- CHAPTER XXXVII.: PRELIMINARIES.

- CHAPTER XXXVIII.: DIFFERENTIAL RENT. GENERAL REMARKS.

- CHAPTER XXXIX.: THE FIRST FORM OF DIFFERENTIAL RENT. (Differential Rent I.)

- CHAPTER XL.: THE SECOND FORM OF DIFFERENTIAL RENT. (Differential Rent II.)

- CHAPTER XLI.: DIFFERENTIAL RENT II.—FIRST CASE: CONSTANT PRICE OF PRODUCTION.

- CHAPTER XLII.: DIFFERENTIAL RENT II.—SECOND CASE: FALLING PRICE OF PRODUCTION.

- CHAPTER XLIII.: DIFFERENTIAL RENT NO. II.—THIRD CASE: RISING PRICE OF PRODUCTION.

- CHAPTER XLIV.: DIFFERENTIAL RENT EVEN UPON THE WORST SOIL UNDER CULTIVATION.

- CHAPTER XLV.: ABSOLUTE GROUND-RENT.

- CHAPTER XLVI.: BUILDING LOT RENT. MINING RENT. PRICE OF LAND.

- CHAPTER XLVII.: GENESIS OF CAPITALIST GROUND-RENT.

- PART VII.: THE REVENUES AND THEIR SOURCES.

Text

[9]PREFACE

by Frederick Engels↩

AT last I have the pleasure of making public this third volume of the main work of Marx, the closing part of his economic theories. When I published the second volume, in 1885, I thought that the third would probably offer only technical difficulties, with the exception of a few very important sections. This turned out to be so. But that these exceptional sections, which represent the most valuable parts of the entire work, would give me as much trouble as they did, I could not foresee at that time any more than I anticipated the other obstacles, which retarded the completion of the work to such an extent.

In the first place it was a weakness of my eyes which restricted my time of writing to a minimum for years, and which permits me even now only exceptionally to do any writing by artificial light. There were furthermore other labors which I could not refuse, such as new editions and translations of earlier works of Marx and myself, revisions, prefaces, supplements, which frequently required special study, etc. There was above all the English edition of the first volume of this work, for whose text I am ultimately responsible and which absorbed much of my time. Whoever has followed the colossal growth of international socialist literature during the last ten years, especially the great number of translations of earlier works of Marx and myself, will agree with me in congratulating myself that there is but a limited number of languages in which I am able to assist a translator and which compel me to accede to the request for [10] a revision. This growth of literature, however, was but an evidence of a corresponding growth of the international working class movement itself. And this imposed new obligations on me. From the very first days of our public activity, a good deal of the work of negotiation between the national movements of socialists and working people in the various countries had fallen on the shoulders of Marx and myself. This work increased to the extent that the movement as a whole gained in strength. Up to the time of his death, Marx had borne the brunt of this burden. But after that the ever swelling amount of work had to be done by myself alone. Meanwhile the direct intercourse between the various national labor parties has become the rule, and fortunately it is becoming more and more so. Nevertheless my assistance is still in demand a good deal more than is agreeable to me in view of my theoretical studies. But if a man has been active in the movement for more than fifty years, as I have, he regards the work connected with it as a duty, which must not be shirked, but immediately fulfilled. In our stirring times, as in the 16th century, mere theorizers on public affairs are found only on the side of the reactionaries, and for this reason these gentlemen are not even theoretical scientists, but simply apologists of reaction.

The fact that I live in London implies that my intercourse with the party is limited in winter to correspondence, while in summer time it largely takes place by personal interviews. This fact, and the necessity of following the course of the movement in a steadily growing number of countries and a still more rapidly increasing number of party organs, compelled me to reserve matters which brooked no interruption for the winter months, preferably the first three months of the year. When a man is past seventy, his brain's fibers of association work with a certain disagreeable slowness. He [11] does not overcome interruptions of difficult theoretical problems as easily and quickly as formerly. Thus it came about that the work of one winter, if it was not completed, had to be largely done over the following winter. And this took place particularly in the case of the most difficult section, the fifth.

The reader will observe by the following statements that the work of editing the third was essentially different from that of the second volume. Nothing was available for the third volume but a first draft, and it was very incomplete. The beginnings of the various sections were, as a rule, pretty carefully elaborated, or even polished as to style. But the farther one proceeded, the more sketchy and incomplete was the analysis, the more excursions it contained into side issues whose proper place in the argument was left for later decision, the longer and more complex became the sentences, in which the rising thoughts were deposited as they came. In several places, the handwriting and the treatment of the matter clearly revealed the approach and gradual progress of those attacks of ill health, due to overwork, which at first rendered original work more and more difficult for the author and finally compelled him from time to time to stop work altogether. And no wonder. Between 1863 and 1867, Marx had not only completed the first draft of the two last volumes of Capital and made the first volume ready for the printer, but had also mastered the enormous work connected with the foundation and expansion of the International Workingmen's Association. The result was the appearance of the first symptoms of that ill health which is to blame for the fact that Marx did not himself put the finishing touches to the second and third volumes.

I began my work on these volumes by first dictating the entire manuscript of the original, which was often hard to decipher even for me, into readable copy. This required considerable [12] time to begin with. It was only then that the real work of editing could proceed. I have limited this to the necessary minimum. Wherever it was sufficiently clear, I preserved the character of the first draft as much as possible. I did not even eliminate repetitions of the same thoughts, when they viewed the subject from another standpoint, as was Marx's custom, or at least expressed the same thought in different words. In cases where my alterations or additions are not confined to editing, or where I used the material gathered by Marx for independent conclusions of my own, which, of course, are made as closely as possible in the spirit of Marx, I have enclosed the entire passage in brackets and affixed my initials. My footnotes may not be inclosed in brackets here and there, but wherever my initials are found, I am responsible for the entire note.

It is natural for a first draft, that there should be many passages in the manuscript which indicate points to be elaborated later on, without being followed out in all cases. I have left them, nevertheless, as they are, because they reveal the intentions of the author relative to future elaboration.

Now as to details.

For the first part, the main manuscript was serviceable only with considerable restrictions. The entire mathematical calculation of the relation between the rate of surplus-value and the rate of profit (making up the contents of our chapter III) is introduced in the very beginning, while the subject treated in our chapter I is considered later and incidentally. Two attempts of Marx at rewriting were useful in this case, each of them comprizing eight pages in folio. But even these were not consecutively worked out. They furnished the substance of what is now chapter I. Chapter II is taken from the main manuscript. There were quite a number of incomplete mathematical elaborations of chapter [13] III, and in addition thereto an entire and almost complete manuscript, written in the seventies and dealing with the relation of the rate of surplus-value to the rate of profit, in the form of equations. My friend Samuel Moore, who had done the greater portion of the translation of the first volume, undertook to edit this manuscript for me, a work for which he was certainly better fitted than I, since he graduated from Cambridge in mathematics. By the help of his summary, and with an occasional use of the main manuscript, I completed chapter III. Nothing was available for chapter IV but the title. But as the point of issue, the effect of the turn-over on the rate of profit, is of vital importance, I have elaborated it myself. For this reason the whole chapter has been placed between brackets. It was found in the course of this work, that the formula of chapter III for the rate of profit required some modification, in order to be generally applicable. Beginning with chapter V, the main manuscript is the sole basis for the remainder of Part I, although many transpositions and supplements were needed for it.

For the following three parts I could follow the original manuscript throughout, aside from editing the style. A few passages, referring mostly to the influence of the turn-over, had to be brought into agreement with my elaboration of chapter IV; these passages are likewise placed in brackets and marked with my initials.

The main difficulty was presented by Part V, which treated of the most complicated subject in the entire volume. And it was just at this point that Marx had been overtaken by one of those above-mentioned serious attacks of illness. Here, then, we had no finished draft, nor even an outline which might have been perfected, but only a first attempt at an elaboration, which more than once ended in a disarranged mass of notes, comments and extracts. I tried at first to complete [14] this part, as I had the first one, by filling out vacant spaces and fully elaborating passages that were only indicated, so that it would contain at least approximately everything which the author had intended. I tried this at least three times, but failed every time, and the time lost thereby explains most of the retardation. At last I recognized that I should not accomplish my object in this way. I should have had to go through the entire voluminous literature of this field, and the final result would have been something which would not have been Marx's book. I had no other choice than to cut the matter short, to confine myself to as orderly an arrangement as possible, and to add only the most indispensable supplements. And so I succeeded in completing the principal labors for this part in the spring of 1893.

As for the single chapters, chapters XXI to XXIV were, in the main, elaborated by Marx. Chapters XXV and XXVI required a sifting of the references and an interpolation of material found in other places. Chapters XXVII and XXIX could be taken almost completely from the original manuscript, but chapter XXVIII had to be arranged differently in several places. The real difficulty began with chapter XXX. From now on the task before me was not only the arrangement of the references, but also a connecting of the line of reasoning, which was interrupted every moment by intervening clauses, deviations from the main point, etc., and taken up incidentally in quite another place. Thus chapter XXX came into existence by means of transpositions and eliminations utilized in other places. Chapter XXXI, again, was worked out more connectedly. But then followed a long section in the manuscript, entitled "The Confusion," consisting of nothing but extracts from the reports of Parliament on the crises of 1848 and 1857, in which the statements of twenty-three business men, and writers on economics, especially [15] relative to money and capital, gold exports, over-speculation, etc., are collected and accompanied here and there with short and playful comments. In this collection, all the current views of that time concerning the relation of money to capital are practically represented, either by answers or questions, and Marx intended to analyze critically and satirically the confusion revealed by the ideas as to what was money, and what capital, on the money-market. I convinced myself after many experiments that this chapter could not be composed. I have used its material, particularly that criticized by Marx, wherever I found a connection for it.

Next follows in tolerable order the material which I have placed in chapter XXXII. But this is immediately followed by a new batch of extracts from reports of Parliament on every conceivable subject germane to this part, intermingled with comments of the author. Toward the end these comments are mainly directed toward the movement of money metals and the quotations of bills of exchange, and they close with miscellaneous remarks. On the other hand, chapter XXXV, entitled "Precapitalist Conditions," was fully elaborated.

Of all this material, beginning with the "Confusion," and using as much of it as had not been previously placed otherwise, I made up chapters XXXIII to XXXV. Of course this could not be done without considerable interpolations on my part in order to complete the connections. Unless these interpolations are of a merely formal nature, they are expressly marked as belonging to me. In this way I have succeeded in placing all the relevant statements of the author in the text of this work. Nothing has been left out but a small portion of the extracts, which either repeated statements already made previously, or touched on points which the original manuscript did not treat in detail.

[16]The part dealing with ground-rent was much more fully elaborated, although not properly arranged. This is apparent from the fact that Marx found it necessary to recapitulate the plan of the entire part in chapter XLIII, which was the last portion of the section on rent in the manuscript. This was so much more welcome to the editor, as the manuscript began with chapter XXXVII, which was followed by chapters XLV to XLVII, whereupon chapters XXXVIII to XLIV came next in order. The greatest amount of labor was involved in getting up the tables for the differential rent, II and in the discovery that the third case of this class of rent, which belonged in chapter XLIII, had not been analyzed there.

Marx had made entirely new and special studies for this part on ground rent, in the seventies. He had studied for years the originals of the statistical reports and other publications on real estate, which had become inevitable after the "reform" of 1861 in Russia. He had made extracts from these originals, which had been placed at his disposal to the fullest extent by his Russian friends, and he had intended to use these notes for a new elaboration of this part. Owing to the variety of forms represented by the real estate and the exploitation of the agricultural producers of Russia, this country was to play the same role in the part on ground rent that England did in volume I in the case of industrial wage-labor. Unfortunately he was prevented from carrying out this plan.

The seventh part, finally, was fully written out, but only as a first draft, whose endlessly involved periods had to be dissected, before they could be presented to the printer. Of the last chapter, only the beginning existed. In it the three great classes of developed capitalist society, land owners, capitalists and wage laborers, corresponding to the three great forms of [17] revenue, and the class-struggle necessarily arising with their existence, were to be presented as the actual outcome of the capitalist period. It was a habit of Marx to reserve such concluding summaries for the final revision, so that the latest historical developments furnished him with never failing regularity with the proofs of the correctness of his theoretical analyses.

The quotations and extracts corroborating his statements are considerably less numerous than in the first volume, as they already were in the second. Wherever the manuscript referred to statements of earlier economists, only the name was given as a rule, and the quotations were to be added later. Of course, I had to leave this as it was. Of reports of parliament only four have been used, but these were abundantly exploited. They are the following:

1) Reports from Committees (of the Lower House), Volume VIII, Commercial Distress, Volume II, Part I, 1847-48. Minutes of Evidence. Quoted as "Commercial Distress, 1847-48."

2) Secret Committee of the House of Lords on Commercial Distress, 1847. Report printed 1848. Evidence printed 1857 (because it was considered too hazardous in 1848).—Quoted as "Commercial Distress, 1848-57."

3) 8 4) Report, Bank Acts, 1857.—The same, 1858.—Reports of the Committee of the Lower House on the Effect of the Bank Acts of 1844 and 1845. With evidence.—Quoted as "Bank Acts," or "Bank Committee," 1857 or 1858.

I hope to start on the fourth volume, the history of theories of surplus-value, as soon as conditions will permit me.

In the preface to the second volume of Capital I had to square accounts with those gentlemen, who were making much [18] ado over the alleged fact that they had discovered in the person of Rodbertus the "Secret source and a superior predecessor to Marx." I offered them an opportunity to show what the economics of Rodbertus could accomplish. I asked them to demonstrate the way "in which an equal average rate of profit can and must come about, not only without a violation of the law of value, but by means of it." These same gentlemen, who were then celebrating the brave Rodbertus as an economist star of the first magnitude, either for subjective or objective reasons which were as a rule anything but scientific, have without exception failed to answer the problem. However, other people have thought it worth their while to occupy themselves with this problem.

In his critique of the second volume (Conrad's Jahrbücher, XI, 1885, pages 452-65), Professor Lexis takes up this question, although he does not pretend to give a direct solution of it. He says: "The solution of that contradiction" (namely the contradiction between the law of value of Ricardo-Marx and an equal average rate of profit) "is impossible, if the various classes of commodities are considered individually, if their value is to be equal to their exchange-value, and this again equal or proportional to their price." According to him this solution is possible only, if "the determination of value for the individual commodities according to labor is relinquished, the production of commodities viewed as a whole, and their distribution among the aggregate classes of capitalists and laborers regarded from the same point of view....The laboring class receives but a certain portion of the total product,...the other portion falls to the share of the capitalists and represents the surplus-product, as understood by Marx, and accordingly...the surplus-value. The members of the capitalist class divide this entire surplus-value among themselves, not in proportion to the [19] number of laborers employed by them, but in proportion to the amount of capital invested by each one. The land is thereby regarded as belonging in the class of capital-value." The Marxian ideal values determined by the units of labor incorporated in the commodities do not correspond to the prices, but may be "regarded as points of departure of a movement, which leads to the actual prices. These are conditioned on the fact that capitals of equal magnitude demand equal profits." In consequence some capitalists will secure higher prices for their commodities than the ideal values, and others will secure less. "But since the losses or gains of surplus-value mutually balance one another in the capitalist class, the total amount of the surplus-value is the same as though all prices were proportional to the ideal values."

It is evident that the problem has not been solved by any means through these statements, but it has been at least correctly formulated, although in a somewhat loose and shallow manner. And this is, indeed, more than we had a right to expect from a man who prides himself somewhat on being a "vulgar economist." It is even surprising when compared with the handiwork of some other vulgar economists, which we shall discuss later. The vulgar economy of Lexis is of a rather peculiar nature. He says that the gains of the capitalist may be derived in the way indicated by Marx, but there are no reasons that would compel us to accept this view. On the contrary, vulgar economy is said to have a simpler explanation, namely the following: "The capitalist sellers, such as the producer of raw materials, the manufacturer, the wholesale dealer, the retail dealer, all make a profit on their transactions, each selling his product at a higher price than the purchase price, each adding a certain percentage to the price paid by him. The laborer alone is unable to raise the price of his commodity, he is compelled, by his oppressed condition, [20] to sell his labor to the capitalist at a price corresponding to its cost of production, that is to say, for the means of his subsistence....Therefore the capitalist additions to the prices strike the laborer with full force and result in the transfer of a part of the value of the total product to the capitalist class."

Now it does not require much thought to show that this explanation of vulgar economy for the profits of capital amounts to the same thing as the Marxian theory of surplus-value. For Lexis thus admits that the laborers are in just that forced condition of oppression which Marx has described; that they are just as much exploited here as they are according to Marx, because every idler can sell commodities above their value, while the laborer alone cannot do so; and that it is just as easy to build up a plausible vulgar socialism on this theory, as it was to build up another kind of socialism in England on the foundation of Jevons' and Menger's theory of use-value and marginal profit. I strongly suspect that Mr. George Bernard Shaw, were he familiar with this theory of profit, would eagerly extend both hands for it, discard Jevons and Karl Menger, and build on this rock the Fabian church of the future.

In reality, this theory is merely a transcript of the Marxian. What is the fund out of which all these additions to the prices are paid? The "total product" of the working class. And it is due to the fact that the commodity "labor," or, as Marx has it, "labor-power," must be sold below its price. For if it is a common quality of all commodities to be sold at a price above their cost of production, with the sole exception of labor, then labor is sold below the price which is the rule in this world of vulgar economy. The extra profit thus accruing to the capitalist, or to the capitalist class, then arises in the last analysis from the fact that the laborer, after he has made [21] up for the price of his labor-power by reproducing it, must produce a surplus-product for which he is not paid, in other words, he produces surplus-value representing unpaid labor. Lexis is very careful in the choice of his terms. He does not say anywhere outright that this is his own conception. But if it is, then it is evident that he is not one of those vulgar economists, every one of whom is, as he says himself, "a hopeless idiot in the eyes of Marx," but that he is a Marxian disguised as a vulgar economist. Whether this disguise is consciously or unconsciously adopted, is a psychological question which does not interest us at this point. The man who can find this out may also be able to discover how it is that some time ago a man of Lexis' intellectual endowments could defend such nonsense as bimetallism.

The first one who really attempted to answer this question was Dr. Conrad Schmidt in his pamphlet entitled, The Average Rate of Profit, Based on Marx's Theory of Value, Stuttgart, Dietz, 1889. Schmidt seeks to reconcile the details of the formation of commodity prices with the theory of value and with an average rate of profit. The industrial capitalist receives in his product, first, an equivalent for the capital advanced by him, and second, a surplus-product for which he has not paid anything. But in order to earn his surplus-product, he must advance capital for its production. He must employ a certain quantity of materialized labor for the purpose of appropriating this surplus-product. For the capitalist, the capital advanced by him represents the quantity of materialized labor which is socially necessary for the production of his surplus-product. This applies to every industrial capitalist. Now, since commodities, according to the theory of value, are exchanged for one another in proportion to the social labor required for their production, and since the labor necessary for the manufacture [22] of the capitalist's surplus-product is accumulated in the capital of the capitalist, it follows that surplus-products are exchanged in proportion to the capitals required for their production, and not in proportion to the labor actually incorporated in them. Hence the share of each unit of capital is equal to the sum of all produced surplus-values divided by the sum of the capitals employed in production. Accordingly, equal capitals yield equal profits in equal times, and this is accomplished by adding the cost price of the surplus-product figured on the basis of the average profit to the cost price of the paid product and selling both the paid and unpaid product at this increased price. Thus the average rate of profit arises in spite of the fact that, according to Schmidt, the average prices of commodities are determined by the law of value.

This is a very ingenious construction. It is made entirely after the Hegelian model, but it has this in common with the majority of the Hegelian constructions that it is not correct. It makes no difference whether the surplus-product or the paid product is considered. If the theory of value is to be applied directly to the average profit both of these products must be sold in proportion to the socially necessary labor incorporated in them. The theory of value is aimed at the very outset against the idea, derived from the capitalist mode of thought, that the accumulated labor of the past, which is embodied in capital, could be anything else but a certain quantity of finished values, namely also a creator of values greater than itself, seeing that it is an element in production and in the formation of profit. The theory of value demonstrates that living labor alone has this faculty of creating surplus-values. It is well known that the capitalists expect to reap profits in proportion to the magnitude of their capitals, looking upon their advances of capital as a sort of cost price of their profits. But if [23] Schmidt utilizes this conception for the purpose of harmonizing by means of it the prices calculated according to the average rate of profit and those based on the theory of value, he thereby repudiates this theory of value, for he embodies in it as one of its factors a conception which is wholly at variance with it.

Either accumulated labor creates values the same as living labor, and in that case the law of value does not apply.

Or, it is not a creator of values, and in that case Schmidt's demonstration is irreconcilable with the law of value.

Schmidt was misled into straying into this bypath when being quite close to the solution, because he believed that he would have to find as mathematical a formula as possible, by which the agreement of the average price of every individual commodity with the law of value could be demonstrated. But while he has followed a wrong path in this instance, close to the real goal, he shows by the rest of his booklet that he has very understandingly drawn other conclusions from the first two volumes of Capital. His is the honor of having found by independent effort the correct answer given by Marx in the third part of the third volume of his work for the hitherto inexplicable sinking tendency of the rate of profit; and of having furthermore correctly shown the genesis of commercial profit out of industrial surplus-value, and of having made a series of statements concerning interest and ground rent, by which he has anticipated things developed by Marx in the fourth and fifth part of the third volume of his work.

In a subsequent article (Neue Zeit, 1892-93, Nos. 4 and 5), Schmidt tries another way to solve the problem. It amounts to the statement that competition brings about an average rate of profit by causing the emigration of capital from lines of production with profit below the average to [24] lines with profit above the average. There is nothing new in the statement that competition is the great equalizer of profits. But Schmidt tries to prove that this leveling of profits is identical with a reduction of the selling price of commodities produced in excess to a measure in keeping with a price which society can pay for it according to the law of value. The analyses of Marx in this work show sufficiently why this way could not lead to any solution.

After Schmidt, it was P. Fireman who attempted a solution of the problem (Conrad's Jahrbücher, dritte Folge, III, page 793). I shall not discuss his remarks on some of the other aspects of the Marxian analyses. He starts out from the mistaken assumption that Marx wishes to define where he is only analyzing, or that one may look in Marx's work at all for fixed and universally applicable definitions. It is a matter of course that when things and their mutual interrelations are conceived, not as fixed, but as changing, that their mental images, the ideas concerning them, are likewise subject to change and transformation; that they cannot be sealed up in rigid definitions, but must be developed in the historical or logical process of their formation. From this it will be understood why Marx starts out in the beginning of his first volume, where he makes the simple production of commodities his historical premise and then proceeds from this basis to capital, from a simple commodity instead of its ideologically and historically secondary form, a capitalistically modified commodity. Fireman cannot understand that at all. I prefer to pass over these and other side-issues and proceed at once to the gist of the matter. While the author is taught by the theory that surplus-value is proportional to the labor-powers employed, provided a certain rate of surplus-value is given, he learns from experience that profit is proportional to the magnitude of the total capital employed, provided a [25] certain average rate of profit is given. Fireman explains this by saying that profit is merely a conventional phenomenon (which means, in his language, that it belongs to a definite social formation with which it stands and falls). Its existence is simply dependent on capital. If this is strong enough to secure a profit for itself, it is also compelled by competition to bring about the same rate of profit for all capitals. In other words, capitalist production is impracticable without an equal rate of profit. Assuming this to be the mode of production, the quantity of profit for the individual capitalist can depend only on the magnitude of his capital, if the rate of profit is given. On the other hand, profit consists of surplus-value, of unpaid labor. And how is the transformation of surplus-value, determined in quantity by the degree of labor exploitation, into profit, determined in quantity by the magnitude of the employed capital, accomplished? "Simply by selling commodities above their value in all lines of production in which the ratio between...constant and variable capital is greatest, and this implies on the other hand that the commodities are sold below their value in all lines of production in which the ratio between constant and variable capital is smallest, so that commodities are sold at their true value only in lines of production in which the ratio of c:v represents a definite medium magnitude....Is this discrepancy between the prices and values of commodities a refutation of the principle of value? By no means. For since the prices of some commodities rise above value to the same extent that the prices of others fall below it, the total sum of prices remains equal to the total sum of values...the incongruity disappears in the last instance." This incongruity is a "disturbance"; and "in the exact sciences it is not the custom to regard a calculable disturbance as a refutation of a certain law."

[26]On comparing the relevant passages of chapter IX with these statements, it will be seen that Fireman has indeed placed his finger on the salient point. But the undeservedly cool reception given to his able article proves that Fireman still needed many interconnecting links, even after this discovery of his, before he would have been enabled to work out a full and comprehensible solution. Although many were interested in this problem, they were all afraid of burning their fingers with it. And this is due not only to the incomplete form in which Fireman left his discovery, but also to the undeniable faultiness of his conception of the Marxian analyses and his critique of them based on his misconception.

Whenever there is an opportunity to make himself ridiculous by attempting a difficult feat, professor Julius Wolf of Zürich never fails to exhibit himself. He tells us (Conrad's Jahrbücher, neue Folge, II, pages 352 and following) that the entire problem is solved by the relative surplus-value. The production of relative surplus-value rests on the increase of the constant capital as compared to the variable capital. "A plus in constant capital has for its premise a plus in the productive power of the laborers. Since this plus in productive power (by way of cheapening the necessities of life) produces a plus in surplus-value, the direct relation between an increase of surplus-value and an increasing share of the constant capital in the total capital is revealed. A plus in constant capital indicates a plus in the productive power of labor. Therefore, if the variable capital remains the same and the constant capital increases, surplus-value must also increase, and we are in agreement with Marx. This was the problem which we were to solve."

Now Marx says the direct opposite in a hundred passages of the first volume. Furthermore, the assertion that, according to Marx, relative surplus-value increases in proportion [27] as the constant capital is augmented while the variable capital decreases, is so astounding that it defies all parliamentarian language. And finally Mr. Julius Wolf demonstrates in every line that he has neither relatively nor absolutely the least understanding of relative or absolute surplus-value. Truly he says that "at first glance one seems to be in a nest of incongruities," which, by the way, is the only true statement in his whole article. But what does that matter? Mr. Julius Wolf is so proud of his brilliant discovery that he cannot refrain from bestowing posthumous praise on Marx for it and advertising his own fathomless nonsense as a "renewed proof of the acuteness and farsightedness with which Marx has drawn up his critical system of capitalist economy."

But that is not the worst. Mr. Wolf says: "Ricardo likewise claimed that an equal investment of capital yielded equal surplus-values (profit), and that the same expenditure of labor created the same amount of surplus-value. And the question was: How does the one agree with the other? But Marx did not acknowledge this form of the problem. He has doubtless shown (in the third volume), that the second statement is not necessarily a consequence of the law of value, or that it even contradicts his law of value and must, therefore,...be directly repudiated." And thereupon Wolf seeks to find out whether Marx or I made a mistake. Of course, it does not occur to him that he is the one who is wandering in darkness.

It would be an insult to my readers, and a total disregard for the humor of the situation, were I to lose one word about this gem of a passage. I merely wish to add this: With the same boldness, which enabled him to foretell even then what Marx "has doubtless shown" in the third volume, he avails himself of this opportunity to report an alleged gossip among the professors to the effect that Konrad Schmidt's above-named [28] work was "directly inspired by Engels." Mr. Julius Wolf! In the world in which you live it may be customary for a man to challenge others publicly for the solution of some problem and to acquaint his private friends clandestinely with this solution. That you are capable of such a thing is not hard to believe. But that a man need not stoop to such mean tricks in the world in which I live, is shown by the present preface.

Marx had hardly died, when Mr. Achille Loria hastily published an article about him in the Nuova Antologia (April, 1883). He starts out with a biography of Marx full of misinformation, and follows it up with a critique of Marx's public, political and literary activity. He misrepresents the materialist conception of history of Marx and twists it with an assurance which indicates a great purpose. And this purpose was later accomplished. In 1886, the same Mr. Loria published a book entitled La teoria economica delta costituzione politica (The Economic Foundations of Society), in which he announced to his admiring contemporaries that the materialist conception of history, so completely and purposely misrepresented by him in 1883, was his own discovery. True, the Marxian theory is reduced to a rather Philistine level in this book. And the historical illustrations and proofs abound in mistakes which would not be pardoned in a high school boy. But what does that matter? He thinks he has established his claim that the discovery that always and everywhere the political conditions and events are explained by corresponding economic conditions was not made by Marx in 1845, but by Mr. Loria in 1886. At least this is what he has tried to make his countrymen believe, and also some Frenchmen, for his book has been translated into French. And now he can pose in Italy as the author of a new and epoch-making [29] theory of history, until the Italian socialists will find time to strip the illustre Loria of his stolen peacock feathers.

But this is only an insignificant sample of Mr. Loria's style of doing things. He assures us that all of Marx's theories rest on conscious sophistry (un consaputo sofisma); that Marx was not above using false logic, even though he knew it to be so (sapendolitali), etc. And after thus biasing his readers by a whole series of such contemptible insinuations, in order that they may regard Marx as just such an unprincipled upstart as Loria, accomplishing his effects by the same shameless and foul means as this professor from Padua, he has a very important secret for the readers, and incidentally he touches upon the rate of profit.

Mr. Loria says: According to Marx, the amount of surplus-value (which Mr. Loria here mistakes for profit) produced in an industrial establishment under capitalism depends on the variable capital employed in it, since the constant capital does not yield any profit. But this is contrary to fact. For in practice the profit is not measured by the variable, but by the total capital. And Marx himself recognizes this (Vol. I, chapter XI) and admits that the facts seem to contradict his theory. But how does he get over this contradiction? He refers his readers to a subsequent volume which has not yet been published. Loria had previously told his readers with reference to this unpublished volume, that he did not believe that Marx had ever thought for a moment of writing it. And now he exclaims triumphantly: "Not without good reason did I contend that this second volume, which Marx always flings into the teeth of his adversaries without ever publishing it, might very well be a shrewd expedient, to which Marx always resorted whenever scientific arguments failed him (un ingegnoso spediente ideato dal [30] Marx a sostituzione degli argomenti scientifici). And whoever is not convinced after this that Marx stood on the same level of scientific swindle with the illustre Loria, is past all redemption.

We have at least learned this much: According to Mr. Loria, the Marxian theory of surplus-value is absolutely irreconcilable with the fact of a general and equal rate of profit. But at last the second volume of Capital appeared. It contained my public challenge referring to this point. If Mr. Loria had been one of us diffident Germans, he would have felt a certain embarrassment. But he is a bold southerner, he comes from a hot climate and can claim that a cool nerve is a natural requirement for him. The question concerning the rate of profit has been publicly put. Mr. Loria has publicly declared that it is insoluble. And for this very reason he is now going to outshine himself by publicly solving it.

This miracle is accomplished in Conrad's Jahrbücher, N. F., vol. XX, pages 272 and following, in an article dealing with Konrad Schmidt's above-cited pamphlet. After Loria has learned from Schmidt how the commercial profit is made, he sees everything clearly. "Since a determination of value by means of labor-time gives an advantage to those capitalists who invest a greater portion of their capital in wages, the unproductive" (he means commercial) "capital can extort from these privileged capitalists a higher interest" (he means profit) "and thus bring about an equalization between the individual industrial capitalists....For instance, if each of the industrial capitalists A, B, C, use 100 working days and 0, 100, and 200 constant capital respectively in production, and if the wages for 100 working days amount to 50 working days, then every capitalist receives a surplus-value of 50 working days, and the rate of profit is 100% [31] for the first 33.3% for the second, and 20% for the third capitalist. But if a fourth capitalist D accumulates an unproductive capital of 300, which extorts an interest" (profit) "equal in value to 40 working days from A, and an interest of 20 working days from B, then the rate of profit of the capitalists A and B will sink to 20% the same as that of C, and D with his capital of 300 will receive a profit of 60, or a rate of profit of 20%, the same as the other capitalists."

With such astonishing dexterity l'illustre Loria solves sleight of hand fashion the same question which he had declared insoluble ten years previously. Unfortunately he did not betray to us the secret of the way in which the owners of the "unproductive capital" obtain the power to extort from those industrials their extra-profit exceeding the average rate of profit and to keep it in their own pockets in the same way in which the land owner pockets the surplus-profit of the capitalist farmer as ground rent. For according to this the commercial capitalists would be levying upon the industrials a tribute analogous to ground rent and thereby bring about an equalization of the rate of profit. Now, the commercial capital is indeed a very essential factor in the equalization of the rate of profit, as nearly everybody knows. But only a literary adventurer, who in the bottom of his heart cares naught for political economy, can venture the assertion that commercial capital has the magic power to absorb all profits above the average rate of profit, even before this average rate has become established, and to convert it into ground-rent for itself without even requiring any real estate for this purpose. Nor is the assertion less astonishing that commercial capital has the gift of discovering those industrials, whose surplus-value just covers the average rate of profit, and that it considers it an honor to mitigate the [32] fate of those luckless victims of the Marxian law of value by selling its products to them free of charge, without asking as much as a commission for it. What a mountebank a man must be in order to imagine that Marx had to have recourse to such miserable tricks!

But Mr. Loria does not shine in his full glory, until we compare him with his northern competitors, for instance with Mr. Julius Wolf, who was not born yesterday, either. What a small coyote Mr. Wolf seems to be, even in his big volume on Socialism and the Capitalist Order of Society, compared to that Italian! How clumsily, I am almost tempted to say modestly, does he stand forth beside the noble check of the maestro who pretends as a matter of course that Marx is just such a sophist, poor logician, liar and mountebank as Mr. Loria himself, that Marx bamboozles the public with a promise of completing his theory in some future volume which he neither will nor can write, as he very well knows, whenever he gets into a tight place! Unlimited nerve coupled to the smoothness of an eel when slipping through impossible situations, a heroic imperviousness to kicks received by him, a hasty appropriation of the accomplishments of others, an importunate charlatanry of advertising, an organization of fame by the help of a clique of friends—who can equal him in all these?

Italy is the land of classic lore. Since the great time when the morning glow of the modern world rose over it, it produced magnificent characters of unequalled classic perfection, from Dante to Garibaldi. But the time of its degradation under the rule of strangers also bequeathed classic character-masks to it, among them two especially sharply chiseled types, that of Sganarelli and Dulcamara. The classic unity of both is embodied in our illustre Loria.

In conclusion I must take my readers across the Atlantic. [33] Dr. (med.) George C. Stiebeling, of New York, also found a solution of the problem, and a very simple one at that. It was so simple that no one on either side of the ocean cared to take him seriously. This aroused his ire, and he complained about this outrage in an endless number of pamphlets and newspaper articles, on both sides of the great water. He was told in the Neue Zeit that his solution was based entirely on an error in his calculation. But this did not disturb him in the least. Marx had also made many errors of calculation, and yet he was right. Let us, then, take a closer look at Dr. Stiebeling's solution.

"Take two factories working with equal capitals for an equal length of time, but with different proportions of their constant and variable capitals. The total capital (c + v) will be regarded as equal to y, and the difference in the proportion of the constant to the variable capital equal to x. In the first factory, y is equal to c + v, in the second y is equal to (c - x) + (v + x). The rate of surplus-value is therefore in the first factory equal to m/v, and in the second factory equal to m/v-x. I designate as profit (p) the total surplus-value (m), by which the total capital y, or c + v, is augmented in the given time, in other words, p is equal to m. Hence the rate of profit in the first factory is equal to p/y, or m/c+v, and in the second factory likewise equal to p/y, or m/(c-x)-(v+x), that is to say, it is also equal to m/c+v. The...problem solves itself in such a way that, on the basis of the law of value, equal capitals employing unequal quantities of living labor in equal lengths of time, a change in the rate of surplus-value brings about the equalization of an average rate of profit." (G. C. Stiebeling, The Law of Value and the Rate of Profit, New York, John Heinrich.)

[34]In spite of the beautiful clearness of the above calculation, we cannot refrain from asking Dr. Stiebeling this question: How does he know that the sum of surplus-values produced by the first factory is exactly equal to the sum of surplus-values produced in the second factory? He states explicitly that c, v, y and x, that is to say, all the other factors in the calculation, are equal in both factories, but not a word about m. It follows by no means that these two quantities of surplus-value are equal simply because he designates them both by m. On the contrary, this is precisely what must be proved, especially since Dr. Stiebeling also identifies the profit p without further ceremony with the surplus-value m. Now, only two possibilities present themselves. Either the m's are equal, both factories produce equal quantities of surplus-value, and therefore, since both capitals are equal, also equal quantities of profit. If so, then Dr. Stiebeling has taken for granted at the outset what he was called upon to prove. Or, one factory produces more surplus-value than the other, and in that case his entire calculation falls to the ground.

Mr. Stiebeling spared neither pains nor money in building upon this erroneous calculation of his mountains of other calculations and exhibiting them to the public. I can assure him, for his own peace of mind, that nearly all of his calculations are equally wrong, and whenever they are not, they prove something entirely different from what he set out to prove. He proves, for instance, by a comparison of the U. S. census figures for 1870 and 1880 that the rate of profit has actually fallen, but explains this fact wrongly, assuming that he has to correct Marx for working his theory with a never changing, stable, rate of profit. But the third part of the third volume of Capital shows that this "stable rate of profit" in Marxian economics is purely a figment of Dr. [35] Stiebeling's brain, and that the falling rate of profit is due to causes which are just the reverse of those indicated by Dr. Stiebeling. No doubt Dr. Stiebeling has the best intentions, but a man who undertakes to discuss scientific questions should learn above all to read the works of the author, whom he wishes to study, just as they have been written, and especially not to find anything in them which they do not contain.

The outcome of the entire investigation, also in this question, shows once more that the Marxian school is the only one which has accomplished something in this line. When Fireman and Konrad Schmidt read this third volume, they will have good reasons for being well satisfied with the work done by each of them.

VOLUME III.

THE PROCESS OF CAPITALIST

PRODUCTION AS A WHOLE.↩

PART I.: THE CONVERSION OF SURPLUS-VALUE INTO

PROFIT AND OF THE RATE OF SURPLUS-VALUE INTO

THE RATE OF PROFIT.↩

CHAPTER I.: COST PRICE AND PROFIT.↩

IN the first volume we analyzed the phenomena presented by the process of capitalist production, considered by itself as a mere productive process without regard to any secondary influences of conditions outside of it. But this process of production, in the strict meaning of the term, does not exhaust the life circle of capital. It is supplemented in the actual world by the process of circulation, which was the object of our analysis in the second volume. We found in the course of this last-named analysis, especially in part III, in which we studied the intervention of the process of circulation in the process of social reproduction, that the capitalist process of production, considered as a whole, is a combination of the processes of production and circulation. It cannot be the object of this third volume to indulge in general reflections relative to this combination. We are rather interested in locating [38] the concrete forms growing out of the movements of capitalist production as a whole and setting them forth. In actual reality the capitals move and meet in such concrete forms that the form of the capital in the process of production and that of the capital in the process of circulation impress one only as special aspects of those concrete forms. The conformations of the capitals evolved in this third volume approach step by step that form which they assume on the surface of society, in their mutual interactions, in competition, and in the ordinary consciousness of the human agencies in this process.

The value of every commodity produced by capitalist methods is represented by the formula: C = c + v + s. If we subtract the surplus-value s from this value of the product, there remains only an equivalent for the value of the capital c + v expended for the elements used in the production of this commodity.

Take it that the production of a certain article requires the expenditure of a capital of 500 p.st., of which 20 p.st. are consumed by the wear and tear of instruments of production, 380 p.st. spent for materials of production, and 100 p.st. for labor-power. And let the rate of surplus-value be 100%. In that case the value of this product is equal to 400 c + 100 v + 100 s, or 600 p.st.

After deducting the surplus-value of 100 p.st., we have a remaining commodity-capital of 500 p.st., which is only an equivalent for the consumed capital of 500 p.st. This portion of the value of the commodity, which makes good the price of the consumed means of production and the price of the employed labor-power, replaces only the amount paid by the capitalist himself for this commodity and represents, therefore, from his point of view the cost price of this commodity.

However, the cost of this commodity to the capitalist, and the actual cost of this commodity, are two vastly different amounts. That portion of the value of the commodity which consists of surplus-value does not cost the capitalist anything for the reason that it costs the laborer unpaid labor. But on [39] the basis of capitalist production, the laborer plays the role of an ingredient of productive capital as soon as he has been incorporated in the process of production. Under these circumstances the capitalist poses as the actual producer of the commodity. For this reason the cost price of the commodity to the capitalist necessarily appears to him as the actual cost of the commodity. If we designate the cost-price by k, we can transcribe the formula C = c + v + s into the formula C = k + s, that is to say, the value of a commodity is equal to the cost price plus the surplus-value.

In this way the classification of the various values making good the value of the capital consumed in the production of the commodity under the term of cost price expresses, on the one hand, the specific character of capitalist production. The capitalist cost of the commodity is measured by the expenditure of capital, while the actual cost of the commodity is measured by the expenditure of labor. The capitalist cost-price of the commodity, then, is a quantity different from its value, or its actual cost-price. It is smaller than the value of the commodity. For since C = k + s, it is evident that k = C - s. On the other hand, the cost-price of a commodity is by no means a mere heading in capitalist bookkeeping. The actual existence of this portion of value continually exerts its practical influence in the actual production of the commodity, because it must be ever reconverted from its commodity-form, by way of the process of circulation, into the form of productive capital, so that the cost-price of the commodity must always buy anew the elements of production consumed in its creation.

However, the cost-price as a heading in bookkeeping has nothing to do with the formation of the value of a commodity, or with the process of self-expansion of capital. When I know that five-sixths of the value of a commodity worth 600 p.st., or 500 p.st., represent but an equivalent for the capital consumed in its production and suffice only for the purchase of new material elements of the same capital, I know nothing as yet of the way in which these five-sixths representing the cost-price of the commodity are produced, nor do I know anything [40] about the production of the last sixth which constitutes its surplus-value. Nevertheless we shall see in the course of our analysis that the cost-price plays in capitalist economics the false role of a category in the actual production of values.

Let us return to our example. Take it that the value produced by one laborer in an average social working day is represented by 6 shillings in money. In that case the advanced capital of 500 p.st. consisting of 400 c + 100 v represents the values produced in 1666 2/3 working days of ten hours each. Of this amount 1333 1/3 working days are crystallized in the value of the means of production amounting to 400 p.st. (400 c), and 333 1/3 working days are crystallized in the value of labor-power amounting to 100 p.st. (100 v). Having assumed a rate of surplus-value of 100%, the production of the new commodity costs an expenditure of labor-power amounting to 100 v + 100 s, or 666 2/3 working days of ten hours each.

We know, then, as shown in volume I, chapter VII, that the value of the newly created product of 600 p.st. is composed, 1), of the reappearing value of the constant capital of 400 p.st. expended for means of production, and 2), of a newly produced value of 200 p.st. The cost-price of the commodity, or 500 p.st., comprises the reappearing 400 c and one-half of the newly produced value of 200 p.st., that is to say 100 v. In other words, it comprises two elements of the value of the commodity which are of widely different origin.

Owing to the appropriate character of the labor expended during 666 2/3 working days of ten hours each, the value of the means of production consumed in this process, to the amount of 400 p.st., is transferred to the product. This previously existing value thus reappears as an element of the value of the product, but is not created in the process of production of this commodity. It exists as an element of the value of this commodity only for the reason that it previously existed as an element of the invested capital. The expended constant capital, then, is replaced by that portion of the value of the commodity which this capital transfers to the commodity of its own accord in the labor-process. This element of the cost-price, therefore, has an ambiguous meaning. On the one [41] hand it passes into the cost-price of the commodity, because it is an element of that portion of the value of the commodity which replaces consumed capital. And on the other hand it forms an element of the value of the commodity only for the reason that it is the value of consumed capital, or because the means of production cost a certain sum.

It is different with the other element of the cost-price. The 666 2/3 working days expended in the production of the commodity create a new value of 200 p.st. One portion of this new value replaces only the advanced variable capital of 100 p.st., which is the price of the labor-power employed. But this advanced capital-value does not participate in the creation of the new value. So far as the advance of capital is concerned, labor-power counts as a value. But in the process of production, labor-power performs the function of creating value. The place of the mere value of labor-power in the advance of capital is taken in the actual process of productive capital by living labor-power which creates value.

This difference of the various elements of the value of a commodity which constitute the cost-price becomes evident whenever a change takes place either in the amount of the value of the expended constant capital or in that of the expended variable capital. For instance, let the price of the same means of production, or of the constant portion of capital, rise from 400 p.st. to 600 p.st., or fall to 200 p.st. In the first case it is not only the cost-price of the commodity which rises from 500 p.st. to 600 c + 100 v, or 700 p.st., but also the value of the commodity which rises from 600 p.st. to 600 c + 100 v + 100 s, or 800 p.st. In the second case, it is not only the cost-price which falls from 500 p.st. to 200 c + 100 v, or 300 p.st., but also the value of the commodity which falls from 600 p.st. to 200 c + 100 v + 100 s, or 400 p.st. Because the expended constant capital transfers its own value to the product, therefore the value of the product rises or falls with the absolute magnitude of that capital-value, other circumstances remaining the same. But on the other hand let us assume that, other circumstances remaining the same, the price of the same amount of labor-power rises from 100 p.st. [42] to 150 p.st., or falls from 100 p.st. to 50 p.st. In the first case, the cost-price rises indeed from 500 p.st. to 400 c + 150 v, or 550 p.st., and in the second case it falls from 500 p.st. to 400 c + 50 v, or 450 p.st. But in either case, the value of the commodity remains unchanged at 600 p.st. In the first case it is 400 c + 150 v + 50 s, in the second 400 c + 50 v + 150 s, but in either case it is 600 p.st. The advanced variable capital does not transfer its own value to the product. The place of its value is taken in the product by a new value created by labor. Therefore a change in the value of the absolute magnitude of the variable capital, to the extent that it expresses merely a change in the price of labor-power, does not alter the absolute magnitude of the value of the commodity in the least, because it does not alter anything in the absolute magnitude of the new value created by living labor. Such a change influences only the relative proportion of the magnitudes of the two elements of the new value, one of which forms surplus-value, and the other of which makes good the variable capital and passes into the cost-price of the commodity.

The two elements of the cost-price, in the present case 400 c + 100 v, have only this in common that they are both of them elements of the value of the commodity replacing advanced capital.

But this actual condition of things must necessarily look reversed from the point of view of capitalist production.

The capitalist mode of production is distinguished from a mode of production based on slavery by this fact among others that in the former the value, or the price, as the case may be, of labor-power assumes the form of the value, or price, of labor itself, that is to say, the form of wages. (Volume I, chapter XIX.) The variable portion of the advanced capital, therefore, presents itself as a capital advanced in wages, as a capital-value paying for the value, or price, of all labor expended in production. Take it, for instance, that an average social working day of ten hours is represented by 6 shillings of money. In that case the advance of a variable capital of 100 p.st. expresses in money [43] the value of a product created in 333 1/3 ten-hour days. But this value, being an element of the advance of capital for the purchase of labor-power, is not an element of the productive capital in the actual performance of its function. Its place in the process of production is taken by living labor-power. If the degree of exploitation of this labor-power is 100%, as it is in our illustration, then it is expended during 666 2/3 ten-hour days, and thereby adds to the product a new value of 200 p.st. On the other hand, the variable capital of 100 p.st. figures in the advance of capital as a capital invested in wages, or as the price of labor performed in 666 2/3 ten-hour days. Dividing 100 p.st. by 666 2/3, we obtain 3 shillings as the price of a working day of ten hours, equal in value to the product of five hours' labor.

Now, if we compare the advance of capital on one side with the value of commodities on the other, we find the following condition of things:

I. Capital advanced 500 p.st., consisting of 400 p.st. of capital expended in means of production (price of means of production) plus 100 p.st. of capital expended in wages (price of 666 2/3 working days, or wages for the same).

II. Value of commodities 600 p.st. of which 500 p.st. represent the cost-price (400 p.st. price of expended means of production plus 100 p.st. price of expended 666 2/3 working days) plus 100 p.st. surplus-value.

In this formula, the portion of capital invested in labor-power differs from that invested in means of production (such as cotton or coal) only by serving for the payment of a substantially different element of production. But it does not differ by serving in a different function in the process of creating the value of the commodities, and thereby in the process of self-expansion of capital. The price of the means of production reappears in the cost-price of the commodities, just as it figured in the advance of capital, and it does so for the reason that the means of production have been appropriately consumed. The cost-price of the commodities also contains the price, or wages, for the 666 2/3 working days consumed in the production of these commodities, which wages [44] figured also in the advance of capital, likewise for the reason that this amount of labor has been appropriately expended. We see only finished and existing values, representing portions of the value of advanced capital which have passed into the value of the product, but no element representing newly created values. The distinction between constant and variable capital has disappeared. The entire cost-price of 500 p.st. now has the ambiguous meaning that it is that portion of the value of commodities worth 600 p.st. which makes good the capital of 500 p.st. expended in the production of these commodities, and that it owes its existence as a portion of the value of these commodities only to the fact of having previously existed as the cost-price of the consumed elements of production, namely means of production and labor, in other words, of having existed as an advance of capital. The capital-value reappears as the cost-price of commodities, because it had been expended as a capital-value.

The fact that the various elements of the value of the advanced capital have been expended for substantially different elements of production, namely for instruments of labor, raw materials, auxiliary substances, and labor, requires only that the cost-price of the commodities should buy a new supply of these substantially different elements of production. So far as the formation of this cost-price is concerned, only one distinction is appreciable, namely that between fixed and circulating capital. In our example we had set down 20 p.st. for wear and tear of instruments of labor (400 c being composed of 20 p.st. for wear and tear of instruments of labor and 380 p.st. for materials of production). Supposing the value of those instruments of labor to have been 1200 p.st. before the productive process began, it will exist after the production of the commodities in two forms, one of them being represented by 20 p.st. of the value of the commodities, and the other by 1200—20, or 1180 p.st., the remaining value of the instruments of labor in the possession of the capitalist, in other words, an element of his productive, not of his commodity-capital. On the other hand, the materials of production and wages, differ from the instruments of labor by being entirely consumed [45] in the production of the commodities and transferring their entire value to that of the produced commodities. We have seen that the turn-over bestows upon these different elements of the advanced capital the forms of fixed and circulating capital.

The advance of capital, according to this, is 1680 p.st., consisting of 1200 p.st. of fixed capital plus 480 p.st. of circulating capital (380 p.st. of which are materials of production and 100 p.st. of which are wages).

But the cost-price of the commodities is only 500 p.st., namely 20 p.st. for the wear and tear of the fixed capital, and 480 p.st. for circulating capital.

This difference between the cost-price of the commodities and the advance of capital merely proves that the cost-price of the commodities is formed exclusively by the capital actually consumed in their production.

In the production of the commodities, instruments of production valued at 1200 p.st. are employed, but only 20 p.st. of this advanced capital are consumed in production. The employed fixed capital, then, passes only partially into the cost-price of commodities, because it is consumed only by degrees in their production. The employed circulating capital passes entirely into the cost-price of commodities, because it is entirely consumed in production. But what else does this prove than that the consumed portions of fixed and circulating capital, in the ratio of the magnitude of their values, pass uniformly into the cost-price of the commodities, and that this portion of the value of commodities originates solely with the capital consumed in their production? If this were not the case, it would be inexplicable why the advanced fixed capital of 1200 p.st. should not add, aside from the 20 p.st. which it loses in the productive process, also the other 1180 p.st. which it does not lose therein.

This difference between fixed and circulating capital with reference to the calculation of the cost-price affirms, we repeat, the apparent origin of the cost-price in the expended capital-value, or in the price paid by the capitalist himself for the expended elements of production, including labor. [46] On the other hand, the variable portion of capital invested in labor-power is explicitly identified, under the head of circulating capital, with that portion of the constant capital which consists of materials of production, so far as the formation of value is concerned. And by this means the mystification of the process of self-expansion of capital is accomplished.1

Hitherto we have considered only one element of the value of commodities, namely the cost-price. We must now occupy ourselves also with the other element of the value of commodities, namely the excess over the cost-price, or the surplus-value. In the first place, then, surplus-value is an excess of the value of a commodity over its cost-price. But since the cost-price is equal to the value of the consumed capital, into whose substantial elements it is continually reconverted, the additional value is an accretion to the capital expended in the production of the commodities and returning by way of the circulation.

We have seen previously that the surplus-value s owes its origin in point of fact to a change in the value of the variable capital v and is, therefore, really but an increment of variable capital. Nevertheless it is also an increment of the expended total capital c + v after the process of production has been completed. The formula c + (v + s), which indicates that s is produced by the conversion of a definite capital-value v, a constant magnitude, into a fluctuating magnitude by means of the labor-power paid by it, may also be represented as (c + v) + s. Before production began, we had a capital of 500 p.st. After production is completed, we have the same capital of 500 p.st. plus an increment of value amounting to 100 p.st.2

[47]However, the surplus-value is an increment, not only of that portion of the advanced capital which is assimilated by the process of production, but also of that portion which is not assimilated. In other words, it is an accretion, not only to the consumed capital which is made good by the cost-price of commodities, but also to the aggregate capital invested in production. Before the beginning of the production we had a capital valued at 1680 p.st., namely 1200 p.st. of fixed capital invested in instruments of production, only 20 p.st. of which are assimilated in the process by the commodities through wear and tear, plus 480 p.st. of circulating capital invested in materials of production and wages. At the close of the process of production we have 1180 p.st. remaining of the value of the productive capital plus a commodity-capital of 600 p.st. By adding these two amounts, we find that the capitalist now has values amounting to 1780 p.st. After deducting his invested total capital of 1680 p.st., the capitalist pockets a surplus of 100 p.st. In short, the 100 p.st. of surplus-value form as much an increment of the invested 1680 p.st. as of the 500 p.st., or that part of it which was assimilated by the production.