David M. Hart, “The Paris School of Liberal Political Economy, 1803–1853”

Date: 4 Sept. 2022

A PDF version of this paper is also available. It was created from MS Word and includes the notes as footnotes rather than endnotes. [1.2 MB].

In addition to the main text of the paper we have included three appendices:

- A list of the members of the three generations of individuals who made up the "Paris School"

- A biographical appendix of the key figures in the School

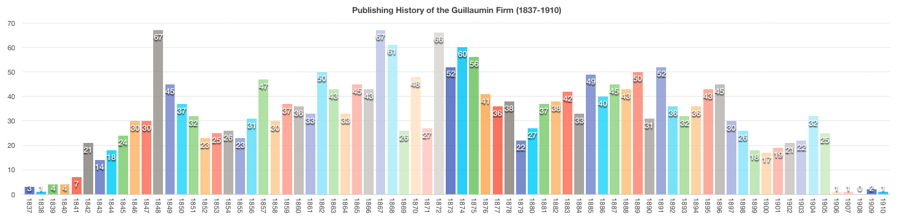

- An analysis of the publishing history of the Guillaumin firm 1837-1910

|

|

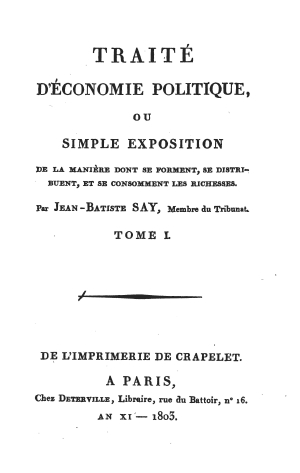

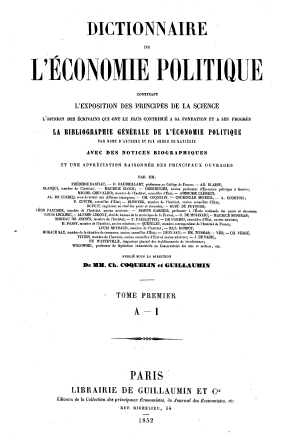

| Title page of the 1st edition of Say's Traité d'économie politique (1803) | Title page of vol. 1 of the Dictionnaire de l'économie politique (1852) |

At this website we have PDFs of the main works of the following key members of the Paris School:

- First Generation:

- Second Generation:

- Third Generation:

As well as the following important texts:

- Journal des Économistes

- Dictionnaire de l'économie politique

- Collection des Principaux Économistes

- a collection of Guillaumin catalogs

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Naming the School

- Various Streams of Thought and their History

- What the Paris School believed in and what they opposed

- The Three Generations of the Paris School

- Part I: The First Generation during The Empire (1803–1815) and the Restoration (1815–1830)

- Part II: The Second and Third Generations during the July Monarchy (1830–1848) and Second Republic (1848–1852)

- Introduction

- Economic and Political (Policy) Issues

- Theoretical Issues

- Conclusion to Part II.

- Conclusion: The School’s Importance

- The Originality and Radicalism of the Paris School

- Their Rediscovery in the late 20th and early 21st Centuries

- Bibliography

- Appendix: The Three Generations of the Paris School

- Biographical Appendix of the Paris School

- The Precursors

- The First Generation

- Claude Destutt de Tracy (1754–1836)

- Benjamin Constant (1767–1830)

- Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832)

- Joseph Droz (1773–1850)

- Charles Comte (1782–1837)

- Charles Dunoyer (1786–1862)

- François-Eugène-Gabriel, duc d’Harcourt (1786–1865)

- Pellegrino Rossi (1787–1848)

- Henri Jean Étienne Boyer-Fonfrède (1788–1841)

- The Second Generation

- Alphonse de Lamartine (1790–1869)

- Hippolyte Philibert Passy (1793–1880)

- Augustin-Charles Renouard (1794–1878)

- Horace Say (1794–1860)

- Augustin Thierry (1795–1856)]

- Antoine-Elisée Cherbuliez (1797–1869)

- Eugène Daire (1798–1847)

- Louis Reybaud (1798–1879)]

- Jérôme Adolphe Blanqui (1798–1854)

- Hippolyte Dussard (1798–1879)

- Louis Leclerc (1799–1854)

- Theodore Fix (1800–1846).

- Gilbert Guillaumin (1801–1864)

- Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850)

- Charles Coquelin (1802–1852)

- Léon Faucher (1803–54)

- Jules Dupuit (1804–1866)

- Ambroise Clément (1805–86)]

- Michel Chevalier (1806–1879)

- Hortense Cheuvreux (née Girard) (1808–1893)

- Roger-Anne-Paul-Gabriel de Fontenay (1809–91)

- Louis Wolowski (1810–76)]

- Joseph Garnier (1813–1881)

- Jean-Gustave Courcelle-Seneuil (1813–1892)]

- The Third Generation

- Appendix on the Publishing History of the Guillaumin Firm

- Endnotes

Introduction↑

Head quote (Say on “administrative gangrene” (1819)

| (E)n général on gouverne trop … (mais) comment s’y prendre pour simplifier une machine administrative compliquée où les intérêts privés ont gagné du terrain sur l’intérêt public, comme une gangrène qui s’avance dans un corps humain lorsqu’elle n’est pas repoussée par le principe de vie qui tend à le conserver ?. Pour guérir cette maladie il faut observer comment s’étend la gangrène administrative. Tout homme qui exerce un emploi tend à augmenter l’importance de ses fonctions, soit pour faire preuve d’un zèle qui lui procure de l’avancement, soit pour rendre son emploi plus nécessaire et mieux payé, soit pour exercer plus de pouvoir, augmenter le nombre des personnes obligées d’avoir recours à lui et de solliciter sa bienveillance. Le remède doit suivre une marche contraire et tendre à diminuer les attributions. | In general we are governed too much … (but) how do we go about reducing the size of a complicated administrative machine where private interests have gained ground over the public interest, like a gangrene which advances in a human body if it is not rejected by the life force which tends to protect it? To cure this disease we have to observe how the administrative gangrene is spread. Every person who is employed (by the state) tends to exaggerate the importance of his functions, whether this is to prove his zeal which will get him promoted, or to make his job (seem) more necessary and (thus) get paid more, or to exercise more power and (thus) increase the number of people who are obliged to come to him to sollicite his goodwill. The cure has to follow an opposite path and has to tend towards reducing the number of (their) duties. [Say “Cours à l’Athénée” (1819), 4th Séance, “Suite des consommations publiques,” Oeuvres, vol. IV, p. 117.] |

The Paris School↑

Naming the School

The uniqueness and importance of the “Paris School” of political economy has only recently (2006) got the attention it deserves. The late Michel Leter[1] has meticulously reconstructed the membership of its three generations who were active during the nineteenth century.[2] It was a coherent school of thought with a dense network of personal relationships which were mediated through several institutions and organisations based in Paris and which exerted considerable influence in the mid- and late-nineteenth century. This paper will discuss the emergence of the Paris School in the early years of the nineteenth century and its consolidation over three generations of thinkers into a coherent school of economic and social thought some 50 years later. The beginning and end points for the discussion are 1803, when Jean-Baptiste Say published the first edition of his Traité d’économe politique and the appearance of Guillaumin’s Dictionaire de l’économie politique (1852–53) some fifty years later.

Before Leter, the Austrian economist Murray Rothbard in his history of economic thought (1995) gave due recognition to what he called “the French Smithians” led by J.B. Say which gradually evolved into “the French laissez-faire school” with Frédéric Bastiat as “the central figure.”[3] At the time, the Parisian economists were content to call themselves simply “les Économistes” just as the Physiocrats had done the previous century. Hence, the title of their journal founded in 1841 by Guillaumin, “Journal des économistes” (Journal of THE Economists). It only gradually occurred to some of them to call themselves a particular school of thought as the 1840s wore on, when a number of them came to appreciate the “Frenchness” of their way of looking at economics, as opposed to the English classical school founded by Smith, Malthus, and Ricardo, and their followers in France. This was at first implied with the inclusion of a preponderance of French authors in the 15 volume Collection des Principaux Économistes edited by Eugène Daire beginning in 1840 (of the 15 volumes 10 were by French authors and 5 by the Anglo-Scottish authors Smith, Malthus, Ricardo). In his introductory essay to the volume with works by the late 17th century economist Boisguilbert (1843) Daire claimed that the economists of his day were the most recent “links in the chain of knowledge” which began with Boisguilbert and then moved on to Quesnay, Smith, JBS, Malthus, Ricardo, and finally Rossi. Making French economists like Boisguilbert, Quesnay, J.-B. Say, and Rossi coequals of Smith, Malthus, and Ricardo is a claim no member of the English classical school would ever have made.[4]

The realisation that the Paris economists were not just an offshoot of the Anglo-Scottish school, but something sui generis, became explicit when a small group began to break away from English orthodox thinking on the role of the state (Molinari), central banking (Coquelin), Smithian labour theory of value (Bastiat), Ricardian rent theory (Bastiat), and Malthusian population theory (Bastiat and Fontenay). Bastiat, for instance, came to realise he owed more of his intellectual development to another school of thought, “cette école éminemment française” (this eminently French school), of Say, Destutt de Tracy, Charles Comte, and especially Charles Dunoyer (whom he had read as a youth) than to “l’école de Malthus et de Ricardo” (the school of Malthus and Ricardo), or what his friend Roger de Fontenay rather dismissively called “cette école anglaise” (this English school).[5]

Although Bastiat did not go on to form a school of his own, as Fontenay had hoped, he was recognised by later members of the Paris School as one of its leading members for his contributions to both economic reform and theory. When one of the members of the third generation of the Paris School, Frédéric Passy (1822–1912), was asked by the Swiss Christian Society of Social Economy in 1890 to give a lecture on what they called “L’École de la Liberté” (the School of Liberty) as part of a month long program of lectures reviewing the state of political economy in the French speaking world at the end of the nineteenth century[6] what he gave was, in effect, a kind of requiem for the “Paris School” which he defended before a hostile audience of socialists and other interventionists. Passy acknowledged the importance of Bastiat in his conclusion by calling him “the most brilliant and purest representative of the doctrine of liberty.”

Various Streams of Thought and their History

The Paris School was by no means monolithic in its thinking and had to contend with several sub-currents which flowed within it, as well as countering criticism of its ideas from competing schools outside. Within, it was based upon two different intellectual foundations. The older, home-grown thread which came from the Franco-Physiocratic school or what might be termed “the precursors” of Pierre de Boisguilbert (1646–1714),[7] Richard Cantillon (1680–1734),[8] François Quesnay (1694–1774),[9] Étienne Bonnot de Condillac (1714–80),[10] and Turgot (1727–81).[11] Equally important was the Anglo-Scottish thread of Adam Smith (1723–1790), Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), Thomas Malthus (1766–1858), and David Ricardo (1772–1823).[12]

Members of the Paris School, with the financial backing of Guillaumin, spent a lot of time rediscovering and promoting their diverse intellectual roots as the work of Adolphe Blanqui (1798–1854) and Eugène Daire (1798–1847) in our period reveal. And it would be done again fifty years later by Maurice Block.[13] One of the first three books ever published by the Guillaumin firm when it opened in 1837 was Blanqui’s Histoire d’économie politique en Europe (1837) which was part history of economic thought and part economic history of Europe which went back to the ancient Greeks. It remained in print as long as Guillaumin lived, going through four editions. Guillaumin must have also invested heavily in one of the most ambitious publishing projects of the firm which saw in only its fourth year of operation the publication of the first volume of what would become 16 very large volumes called the Collection des Principaux Économistes under the editorship of Daire. It brought together in print the two threads mentioned above in a dramatic and striking visual way - 16 large volumes, with a total of 11,000 pages of classic texts and new notes by the editors, which could be purchased as a hardcover set for 200 fr. Guillaumin would do the same in its next big publishing project, the Dictionnaire de l’économie politique (1852) which would also have the history of economic thought as a core component.

It is interesting to speculate why they placed so much importance on their intellectual heritage. Several reasons come to mind: they might want to show that free market ideas were not an “English import” but had deep roots in France going back to the 17th century; that there was a long tradition of thinking about economic theory and that this body of thought was a “science” like any other; and that their intellectual forebears had overcome political and other obstacles (the persecution of Boisguilbert by Louis XIV comes to mind) just as they were trying to do in their own time. However, I believe the major reason is that they wanted to show, as Daire eloquently put it in his remark about the “links in the chain of knowledge” that this French tradition continued up to their own day. Yet, how these two intellectual foundations could be reconciled with each other was a constant source of debate during our period. The thread of Boisguilbert-Turgot-Condillac-Say sometimes clashed with the so-called “classical” thread of Smith-Malthus-Ricardo, especially the latter’s notions of value, rent, and population, as the revisionist work of Bastiat in the mid–1840s would show.

Upon these foundations the early members of the Paris School such as Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832), Destutt de Tracy (1734–1836), and Charles Dunoyer (1786–1862), began doing their own innovative work on the entrepreneur, the nature of markets, and the new “industrialist” society which was emerging before their eyes. By the 1840s the school had matured into a well-organised group with its own journals, associations, a publishing firm, and contacts which extended well into the broader political and intellectual life of Paris. The main figures at this time were the publisher Gilbert Guillaumin (1801–1864) whose firm provided a locus for the school’s activities, Adolphe Blanqui (1798–1854), Eugène Daire (1798–1847), Charles Coquelin (1802–1852), and Michel Chevalier (1806–1879). Its main focus was on ending the policy of trade protection and then countering the rise of socialism in the 1848 Revolution.

The school was also developing its own smaller group of “young Turks” (not all of whom were young in age) within it who began pushing the boundaries of the school into new and more radical directions until the outbreak of the February Revolution 1848 forced the entire school to change direction. This latter group of radicals and anti-statists consisted of Charles Coquelin (1802–1852), Gustave de Molinari (1819–1912), and Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850), but their work was cut short through a combination of premature deaths and self-imposed exile from Paris following the rise to power of Louis Napoléon, soon to declare himself Napoléon III.

Outside the Paris School there were several schools of thought which were very hostile to their ideas and the policies based upon those ideas. This included an “Imperialist or Nationalist school” which supported protectionism and state support for favoured industries (Saint-Chamans, Ferrier, Lebastier, Lestisboudois); a “Social Reformist school”, also known as the “Sentimentalist” school, which wanted the state to take a more active role in addressing “the social problem” of poverty and poor living conditions in the factories - this had a religious Catholic version (social Catholicism) (Villeneuve-Bargemont and later Le Play), a Sismondian version (Sismondi), and a liberal version (Lammenais, Montalembert); a “Socialist school” which had various diverse elements within it (Fourier, Blanc, Considerant, Proudhon); and a “Saint-Simonian school” which sought technocratic, state directed reforms and public works - with a free trade version (Chevalier) and a Napoleonic version (Louis Napoléon).

It should also be noted that, at the very end of our period, another school of thought began to emerge which had its roots partly at least in Paris, namely the thought of Karl Marx. He spent time in Paris in the mid and late 1840s, which was the heyday of the Paris School, where he met Friedrich Engels, researched and wrote The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts (1844), and distributed the first copies of “The Communist Manifesto” (1848). Marx had minimal contact with members of the Paris School (discussed below) and his ideas were not known to the latter at this time.

What the Paris School believed in and what they opposed

In spite of differences between individual members of the Paris School there were some things they all by in large agreed upon. These included in general philosophical terms, a belief in individual liberty in both its political and economic dimensions, the right to self ownership and the right to own the things that the self was able to create or produce, and the right to trade one’s justly owned property and services with others both domestically and internationally (free trade).

More specifically, when it came to political liberty they believed in freedom speech, freedom of religion, freedom of association, representative government and a broader franchise, and the rule of law. Concerning economic liberty, they believed in private property, free markets, free trade, sound money, and low and more equally distributed taxes.

They also largely agreed on what they opposed. These included the following: protectionism and subsidies to industry, a state monopoly in education, state funding of churches, censorship, slavery, colonialism, conscription for the standing army, war, and socialism.

In spite of considerable agreement on many fundamental economic and political ideas, the school was divided over several key issues which they were never able to resolve, namely, republicanism vs. a constitutional monarchy, the number of public goods the government should provide, free banking, the cause of business cycles, and the extent of “tutelage” the government should provide for the poor and the ignorant and uneducated.

The Three Generations of the Paris School↑

We can identify three generations of individuals who made up the Paris School, grouped according to when they were born and when they were most active.[14] The first generation of 13 individuals were born under the Old Regime and were active in the Empire (1803–1815) and the Restoration (1815–1830) when the first indications that a coherent school of thought began to emerge. It was in this early stage that we can see the first important productive period between 1815 and 1825 when a number of important books were published and innovative ideas were first introduced. The second generation of 26 individuals were born during the French Revolution and the First Empire and were active during the July Monarchy (1830–1848) and Second Republic (1848–1852). The 1830s was a difficult time for the school as it tried to rebuild itself after a number of deaths depleted their ranks, by working within the newly reconstituted Institute (1832) and creating their own organisations from scratch like the Guillaumin publishing form (1837). The third generation of 23 individuals were born during the Restoration period and were active in the late July Monarchy and later in the century. The period from 1842 to 1852 saw the flowering or “take-off” of the school into a well organised, active, and productive group of very like-minded individuals. This decade was the second important period for the number of important books and new ideas which appeared by members of the school, culminating with the publication of the Dictionnaire de l’économie politique (1852–53). The “flowering” of the Paris school lasted until 1877 when a restructuring of the state university system erected serious impediments to the further expansion of the school, after which it went into a decline which lasted until the death of one of its last major figures, Yves Guyot (1843–1928).

Part I: The First Generation during The Empire (1803–1815) and the Restoration (1815–1830)↑

Head quote (Dunoyer on the “municipalisation of the world” (1825)

C’est l’esprit de domination qui a formé ces agrégations monstrueuses ou qui les a rendues nécessaires; c’est l’esprit d’industrie qui les dissoudra: un de ses derniers, de ses plus grands et de ses plus salutaires effets paraît devoir être de municipaliser le monde. Sous son influence les peuples commenceront par se grouper plus naturellement; on ne verra plus réunis sous une même dénomination vingt peuples étrangers l’un à l’autre, disséminés quelquefois dans les quartiers du globe les plus opposés, et moins séparés encore par les distances que par le langage et les mœurs. Les peuples se rapprocheront, s’aggloméreront d’après leurs analogies réelles et suivant leurs véritables intérêts. … N’ayant plus mutuellement à se craindre, ne tendant plus à s’isoler, ils ne graviteront plus aussi fortement vers leurs centres et ne se repousseront plus aussi violemment par leurs extrémités. Leurs frontières cesseront d’être hérissées de forteresses; elles ne seront plus bordées d’une double ou triple, ligne de douaniers et de soldats. … Dans le même temps, une multitude de localités, acquérant plus d’importance, sentiront moins le besoin de rester unies à leurs capitales; elles deviendront à leur tour des chefs-lieux; les centres d’actions se multiplieront; et finalement les plus vastes contrées finiront par ne présenter qu’un seul peuple, composé d’un nombre infini d’agrégations uniformes, agrégations entre lesquelles s’établiront, sans confusion et sans violence, les relations les plus compliquées et tout à la fois les plus faciles, les plus paisibles et les plus profitables. |

It is the spirit of domination which has formed these monstrous (political) agglomerations (agrégation), or which has made them necessary. It is the spirit of industry which will dissolve them; one of its last, greatest, and most salutary effects appears to have to be the municipalisation of the world. Under its influence, nations/people will begin by grouping together more naturally. We will no longer see united under the same name 20 peoples who are strangers to one another, sometimes dispersed to the four corners of the globe and opposed to each other more by language and customs than even by physical distance. People will draw closer to each other and gather together according to their real similarities and their true interests. … No longer having to fear each other, no longer tending to be isolated from each other, they will no longer gravitate as strongly towards their centres and will no longer be so violently rejected by their (furthest) extremities. Their frontiers will cease bristling with fortresses, they will no longer be surrounded by a double or triple line of customs officers and soldiers. … At the same time, a multitude of places/localities, by acquiring more importance, will feel less need to remain united to their capital (city), they will become in their turn regional centres (chefs-lieux), these centres of activity will multiply, and finally the largest countries will end up by having (présenter = presenting to the world) only a single people/nation composed of an infinite number of similar/identical aggregations, between which will be established, without any confusion or violence, the most complex relations (which will be) at the same time the easiest, most peaceful, and most profitable ones (imaginable). [Dunoyer, L’Industrie et la Morale (1825), FN on p. 366–67.] |

Introduction↑

|

|

|

|

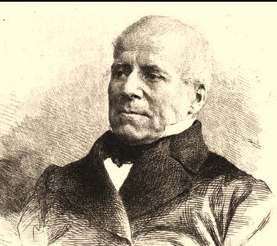

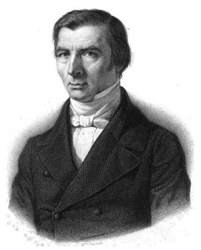

| Antoine-Louis-Claude Destutt de Tracy (1754–1836) | Benjamin Constant (1767–1830) | Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832) | Charles Dunoyer (1786–1862) |

The first generation were born under the Old Regime and were active during the Empire and the Restoration. Its most important members[15] were the Ideologue theorist and politician Claude Destutt de Tracy (1754–1836);[16] the novelist, political theorist, and politician Benjamin Constant (1767–1830);[17] the journalist, politician, cotton manufacturer, and academic Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832);[18] the lawyer, journalist, and academic Charles Comte (1782–1837);[19] and the lawyer, journalist, academic, and politician Charles Dunoyer (1786–1862).[20]

Economic and Political Issues↑

Economic Theory

The school’s focus initially was on addressing the disruptions caused by the conquest and occupation of Europe by Napoléon’s armies, the internal costs of raising mass armies (the “levée en masse” and conscription) and putting the French economy onto a war footing and the bureaucratic and regulatory means to do this, the number of deaths caused by war and disease, the disruption to trade caused by waging economic warfare against England by imposing a blockade on English imports into Europe (the Continental Blockade), Napoleon’s undoing of many liberal economic reforms introduced in the early years of the Revolution, the establishment of the Bank of France to finance the war, and the censorship of critics of the régime (including economists like Tracy and Say, and the journalists Comte and Dunoyer).

They faced a second series of issues when Napoleon was defeated militarily and politically and the Bourbon monarchy was restored to power. The end of the wars brought several years of post-war economic depression as European economies adjusted to the new conditions of peace after 25 years of war and upheaval. The restoration was not only of the Bourbon monarchy, but also of the powers of the nobility, the large landowners, the established Church, and the traditional military. In particular they witnessed the restoration of high tariffs as part of a renewed alliance between the large land owners and industrialists who benefited from the system of high tariffs which France traditionally had imposed upon the country.

The economists responded to these problems in a variety of ways. In terms of economic theory the two most important treatises which appeared in the early years were Destutt de Tracy’s Traité d’économie politique (1811) which first appeared as volume 4 of Eléments d’idéologie (1803–1815, 1817–1818) and then as a stand alone volume in 1823; and Jean-Baptiste Say’s Traité d’économie politique which went through multiple revisions and editions (1803, 1814, 1817, 1819, 1826). Not surprisingly, both had difficulties with Napoleon who opposed their strong defence of free trade and non-intervention in the economy. Say for instance refused to rewrite his Treatise under direct pressure from Napoleon to endorse his policies of protectionism and trade embargoes. He waited until Napoleon was preoccupied elsewhere in 1814 before issuing the second edition which if anything was even more free trade than the first. Destutt de Tracy suffered from Napoleon’s wrath when the latter closed down the Institute’s “Class of Moral and Political Sciences” in 1803 effectively depriving him of influence and boasted that he had coined the name “Idéologues” as a term of abuse to undermine their moral authority. Like Say, Tracy delayed the publication of his volume dealing with political economy until the fall of Napoleon.

Of all the many important things these two authors discussed in their treatises they agreed on a number of key issues which would have a profound impact on the Paris School. First, the idea that government intervention in the economy was an impediment to trade and to the growth of prosperity, as well as a violation of an individual’s natural right to life, liberty, and property. This idea of individual and economic liberty was a foundational concept for the Paris School.

Secondly, that the Physiocrats were wrong to argue that only agriculture was a productive activity. Tracy argued that merchants for example were productive by making it possible for consumers to get the things that producers made.[21] Say argued that entrepreneurs played a key role in bringing together all the factors of production, distribution, and sales without with very little economic activity would take place. Both developed ideas about class that pitted a “productive” or “industrious” class against a “non-productive” or “idle” class which would have important ramifications for the development of a classical liberal theory of class and exploitation in which the Paris School played a vital role.

Thirdly, that it was not just “material goods” like food, cloth, or iron bars which were produced and exchanged but a whole raft of “non-material goods” such as the services of teachers, judges, and opera singers which also could be analysed from an economic perspective. Say in particular was a pioneer in this new way of thinking about what we would call “services” and his early followers Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer spent considerable time trying to determine where to draw the line between “productive” suppliers of services (like that of an opera singer whose performances are voluntarily “purchased” by consumers) and “non-productive” or “parasitical” producers (like government employed bureaucrats or members of the armed forces who are payed with tax-payers’ money whether they wanted those services or not).

Fourthly, that the exchange of goods and services was not just an aspect of society but, in Tracy’s aptly chosen phrase, that society itself was “nothing but a succession of exchanges.”[22] The implication of this idea was that there was not two separate entities that needed to be studied, “society” on the one hand and “the economy” on the other, but rather one entity which was permeated by interlocking political, social, and economic relationships - or a “social economy” if you will. The latter was Say’s preferred name for the field of study in which he was engaged and regretted that fact that the older name “political economy” had become so entrenched it was now near immovable.[23]

With the onset of blindness and increasing age Tracy withdrew from doing more theoretical work. Say on the other hand kept rewriting and expanding his Treatise through five editions spanning thirteen years (1803–1826) doubling its size in the process,[24] writing an even larger work based upon his lectures which was aimed at a broader audience, the Cours complet d’économie politique pratique (1828–29), and several pioneering shorter works of popularisation of economic ideas.[25] It is most unfortunate that this key figure’s Treatise still does not have a modern scholarly English edition and that the Cours complet has never been translated into English at all.

The Impact of Say’s Economics on Liberal Political and Social Theory

Say’s new theory of “social economy” had a profound impact on two of the leading defenders of classical liberal political theory in the late Empire and early Restoration, Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer, and also to a lesser but still very substantial degree on Benjamin Constant.[26] Comte and Dunoyer had trained as lawyers and had started a small circulation journal Le Censeur in June 1814 in which they denounced the strict censorship laws and disregard for constitutional limits on state power for which they ran afoul of the censors in both the late Napoleonic régime and the newly restored Bourbon monarchy.[27] By an irony of history, when their magazine was forced to close in September 1815 they spent their time defending themselves in court as well as reading the latest books which had been released. One of these was the second revised edition of Say’s Treatise (1814) which hit the young lawyers like a bombshell, completely transforming their understanding of what liberal theory was or could be. When they re-opened their journal in February 1817 it was now called Le Censeur européen and was filled with very different kinds of articles dealing with reviews of Say’s books, an analysis of the history and functions of the “productive classes” (les industrieux) which produced the wealth which made society possible, the exploitation of the “industrious class” by the “unproductive classes” (usually associated with the state or groups privileged by the state in some way), the inevitable resistance to this exploitation by the industrious classes which resulted in revolution (whether the English Revolution of the 17th century or the more recent French Revolution), and a whole new theory of the evolution of societies through various economic stages which culminated in the rise of a new stage of “industrialism” which France was now on the verge of entering.[28] This flurry of activity was the start of a research agenda which lasted the two scholars another 20 years and had an enormous impact on the the rising generation of French classical liberals (most notably Frédéric Bastiat).

The direct influence of Say’s new interpretation is harder to identify in the case of Benjamin Constant (and also on the novelist Stendhal)[29] but one can also see Constant’s liberalism moving in a new direction at this time which also increasingly addressed economic matters. We can see it in his essay De l’esprit de conquête et de l’usurpation (1814) (with references to industry and commerce), in his famous lecture given at the Athénée royal de Paris on “De la liberté des anciens comparée à celles des modernes” (especially with his many references to the place of commerce in modern societies), the chapters dealing with economic matters in Les Principes de Politique (1806, 1815), in “De la liberté de l’industrie” (1818) in Collection complète (1818), and then in most detail in his long-forgotten Commentaire sur l’ouvrage de Filangieri (1822–24) (with his discussions of the privileged class and the rulers vs. the ruled).[30]

After Constant was elected to the Chamber of Deputies in March 1817 representing La Sarthe he was one of the few advocates for free trade when the matter came up for discussion in April and May 1821. The leading defenders of protectionism were Auguste Louis Philippe vicomte de Saint-Chamans (1777–1860),[31] who was a member of the Chamber of Deputies and the Council of State, and François-Louis-Auguste Ferrier (1777–1861), who had served as director general of the Customs Administration during the Empire.[32] They both gave fairly standard defenses of tariff protection and subsidies for domestic industry in the name of building a strong national economy. Benjamin Constant had been able to get appointed to the investigating committee which was headed by the wealthy land owner and royalist Deputy (Tarn) Marie-Joseph Dor de Lastours whose plan was to divide the country into 4 zones which would each have different regulations regarding what could or could not be imported or exported, to establish government financed grain storage depots to put aside surplus grain for periods of shortage, and to introduce a system of different sliding scales of prices for each zone which would trigger import bans or when the government would set prices for the sale of grain. The best the free traders like Constant could do was to amend the legislation so that the 12–15,000 largest landowners did not get all the spoils and that the interests of the other 6 million small land holders in France would get equal treatment. In a withering speech to the Chamber Constant declared himself to be “en état de défiance” (in a state of defiance) towards the government bill and clearly described the class interests which lay behind the measure.[33] Constant’s protests were in vain. The bill passed 282 to 54 on July 45, 1821 nearly doubling the rate of tariffs in some areas of France. However, following this spirited defense of free trade in the Chamber Constant wrote his one and only “treatise” on economics in the form of a lengthy commentary on the work of the Italian jurist Gaetano Filangieri which appeared in 1822 and contained a section on the benefits of free trade.

Returning to the fates of Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer, after a series of arrests and trials Comte’s activities as journalist were suspended in 1819[34] and he was forced into exile to escape a two year prison sentence. He found refuge in Switzerland where he was able to secure a professorship in natural law at the University of Lausanne (1820–23) before pressure from the vengeful French government forced him to move to England (1823–26), where he met Jeremy Bentham and other members of the classical school of political economy. Comte eventually returned to Paris to turn his Swiss lectures on law and economics into the prize-winning book Traité de législation (1827) and its sequel Traité de la propriété (1834) in which he explored, among other things, the evolution of law and legal institutions, the nature and evolution of property, the class structure of slave societies and the nature of exploitation.[35]

Dunoyer on the other hand was able to remain in Paris and continued work as a journalist, author, and lecturer, publishing the first of a series of books on the evolution of the industrial stage of economic evolution, L’Industrie et la morale considérées dans leurs rapports avec la liberté (1825) which had been given as lectures at the Athénée, and then an expanded version Nouveau traité d’économie sociale (1830) with its obvious reference in the title to Say’s preference for “social economy” over “political economy” as the proper field of study for his intellectual followers.

Say was more fortunate in that he was able to secure a couple of teaching positions in Paris at a time when there were very few such opportunities. He began giving lectures at the private educational institution the Athénée royal (where lectures were open to members of the public) in 1816 following the success of the second edition of his Treatise (1814) and the easing of censorship; he was granted a Chair of “Industrial Economics” (the name “political economy” was seen to be be too radical at the time) at the government funded Conservatoire national des arts et métiers (The National Conservatory of Technical Arts and Trades) in 1819 which he held to his death in 1832; and, being the entrepreneur that he was, he co-founded a private business school, l’École Spéciale de Commerce et d’Industrie (The School for Commerce and Industry) in 1819, where he also taught. When a dedicated chair of political economy was finally created in 1831 following the July Revolution of August 1830 Say was appointed to it but only served a year before he died in November 1832.

The content of these lectures has not been known in any detail until very recently. His Leçons d’économie politique (Lectures on Political Economy) given at the Athénée in 1819 and the Conservatoire between 1820–29 were finally published as part of his Œuvres complètes (2002).[36] They reveal a much more radical side to Say than appears in the printed Treatise and the Cours complet. Here Say seems to cut loose from the strictures imposed by the censors and appears at times to be moving towards the free market version of anarchism which Gustave de Molinari would advocate in 1849.

Conclusion↑

Opposing Currents of Thought

The rise of a small but vocal group of free traders like Say and Constant provoked a protectionist response, especially when the question of tariff reform came up in the Chamber for debate in 1821–22. At this stage the response by defenders of protectionism like Saint-Chamans and Ferrier, was not very sophisticated or urgent as the political challenge posed by the free traders was very weak as result of the very narrow electoral franchise which limited voting to the top 5% of tax payers who were large landowners and industiralists who benefited from tariffs. It would become much more intense 25 years later when tariff reform was discussed again in 1847 at a time when the French Free Trade movement had become organised under Bastiat’s leadership and energised by the success of the free trade Anti-Corn Law League in England in 1846.

We can also see the beginnings of a more sophisticated socialist critique of liberal political economy beginning to emerge during the Restoration. It too would become powerful and threatening enough to absorb most of the Paris School’s attention during the Second Republic, which would be the task of the Second and Third Generations of the Paris School to counter. One such thread was started by Sismondi, who began as a defender of free trade and free markets in De la richesse commerciale (1803) but began to have serious doubts during the economic depression which struck in the years following the end of Napoléon’s Empire in 1815. In Nouveaux principes d’économie politique (1819) he expressed the view that perhaps the “capitalist system” had a built-in tendency to impoverish the poorest members of society who could not survive the rigours of competition or the threat of impoverishment caused by overpopulation without some government regulation. The Paris economists, on the other hand, saw these economic recessions as the result of what Bastiat would later call “les causes perturbatrices” (disturbing or disrupting factors) which were due to political interventions in the economy, not the operations of the free market itself. However, this thread of criticism of the free market introduced by Sismondi would persist and even grow stronger during the rest of the century.

A more fundamental critique of the ideas of the Paris School would come from the socialist movement which would develop into a formidable force by the mid–1840s and even take control of one part of the Provisional Government during the early months of the February Revolution of 1848. We can see the first stirrings of the Saint-Simonian school with the appearance of Saint-Simon’s Du système industriel (1821) which was co-written by Augustin Thierry who had been a collaborator of Comte’s and Dunoyer’s on Le Censeur européen, becoming at one stage the editor while Comte and Dunoyer were in the courts fighting the censors.[37] There were some parallels between the theory of “industrialism” of the Comte/Dunoyer group and Saint-Simonians but they split over the question of the role of the state. The “liberal industrialists” wanted the state to adopt a policy of laissez-faire which would allow the productive industrial class to grow and prosper on their own, whereas the “interventionist industrialists” thought the state should guide this development through regulation and planning from the top down. The “interventionist industrialists” in turn split into a more free market group (the most important representative of which was the economist Michel Chevalier) and a socialist group which envisaged a very large and permanent role of the state in all future economic development.

The most thorough-going socialist critique to emerge at this time was Fourier’s, whose book Le Nouveau monde industriel et sociétaire (1829) was published at the very end of the Restoration. He envisaged a complete reorganisation of society both economically and socially with the total abolition of free markets and wage labour. People would “associate” together by living and working in large cooperatives known as “Phalanxes” where there would be no wages paid nor profits made, but all would share in doing the work and receiving the benefits. His ideas about “association” would join with Louis Blanc’s ideas about “organisation” among workers to form the backbone of the socialist challenge to the Paris School’s ideas in the late 1840s.

The End of the First Generation

The first generation of the Paris School came to a figurative and some cases literal end with the overthrow of the the Bourbon monarchy by the Orléanist branch of the family under Louis Philippe in July 1830. Censorship, limited teaching possibilities, exile, and death had depleted their ranks and this weakness in the school would continue in the first few years of the July Monarchy until the Paris School could replenish its ranks with some new blood. They had enjoyed a flowering in the “long decade” between 1814 and 1827 which saw the publication of a revised edition of Say’s Treatise (1814), Constant’s Les Principes de Politique (1815), vol. 4 of Tracy’s Eléments d’idéologie (1817), Dunoyer’s L’Industrie et la morale (1825), and Comte’s Traité de législation (1827).

Four of the leading figures in the first generation were old by the end of the Restoration and died soon afterwards. Constant died in 1830. Say in 1832, Tracy in 1836, and Charles Comte in 1837. They left a significant gap which would be hard to replace, but it was when a new generation of the Paris School emerged in the late 1830s and began to flourish in the early 1840s.

Part II: The Second and Third Generations during the July Monarchy (1830–1848) and Second Republic (1848–1852)↑

Head quote (Bastiat on the difference between “good economists and bad economists” (1850)

| Dans la sphère économique, un acte, une habitude, une institution, une loi n’engendrent pas seulement un effet, mais une série d’effets. De ces effets, le premier seul est immédiat ; il se manifeste simultanément avec sa cause, on le voit. Les autres ne se déroulent que successivement, on ne les voit pas ; heureux si on les prévoit. Entre un mauvais et un bon Économiste, voici toute la différence : l’un s’en tient à l’effet visible ; l’autre tient compte et de l’effet qu’on voit et de ceux qu’il faut prévoir. [Bastiat, "Introduction, Ce qu’on voit et ce qu’on ne voit pas (July 1850)] | In the sphere of economics an action, a habit, an institution, or a law engenders not just one effect but a series of effects. Of these effects only the first is immediate; it is revealed simultaneously with its cause; it is seen. The others merely occur successively; they are not seen; we are lucky if we foresee them. The entire difference between a bad and a good Economist is apparent here. A bad one relies on the visible effect, while the good one takes account both of the effect one can see and of those one must foresee. [CW3, p. 403.] |

Introduction↑

Members of the 2nd and 3rd Generations

|

|

|

| Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850) | Michel Chevalier (1806–1879) | Joseph Garnier (1813–1881) |

The gaps left by the passing of the first generation were filled by two new generations of economists who were active in the July Monarchy and the Second Republic, and their very productive period of intellectual activity was the decade between 1842 and 1852.

The second generation of the Paris School were born during the French Revolution and the First Empire,[38] the most important members of which were the book seller and publisher Gilbert Guillaumin (1801–1864);[39] the journalist, free trade activist, and politician Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850);[40] the journalist, editor and advocate of free banking Charles Coquelin (1802–1852);[41] the academic Michel Chevalier (1806–1879);[42] and the academic and peace advocate Joseph Garnier (1813–1881).[43]

|

|

| Gustave de Molinari (1819–1912) | Frédéric Passy (1822–1912) |

The third generation were born during the Restoration period[44] and its most important members who were old enough to have been active in this period were the journalist and academic Gustave de Molinari (1819–1912),[45] the young Ricardo scholar Alcide Fonteyraud (1822–1849),[46] and the politician, peace activist, and academic Frédéric Passy (1822–1912).[47]

Along with some longer lived members of the first generation, a sizable contingent of the Paris School was represented at various levels in the government. We can count three ministers, four Peers of France, 13 elected Deputies, four members of the General Council, five members of the Council of State, two Prefects of Departments, and two ambassadors.[48] For example, following the July Revolution of 1830 Charles Dunoyer entered government perhaps taking at face value the promises of Louis Philippe to introduce more of a constitutional monarchy and lift some of the worst excesses of censorship and limits on political associations which had been the hallmark of the final years of Charles X’s reign. Dunoyer became Prefect of Allier, la Mayenne, and then la Somme, and was appointed a Councillor of State in 1838.[49] Frédéric Bastiat was rewarded for his support in August 1830 with the post of Justice of the Peace in his home town of Mugron in 1831 and then an appointment as a General Councillor in 1833 for whom he wrote a series of important economic monographs on tax reform.[50]

These liberal officials provided a voice in favour of many liberal reforms within the government but without an expanded electorate of supporters (as produced in England by the First Reform Act of 1832) they did not have the clout to push through those reforms in the face of the unbending opposition of Louis Philippe’s various governments, as their failure to achieve any tariff reform after a government inquiry in the first half of 1847 proves. It soon became clear that the governments headed by François Guizot and Adolphe Thiers were royalist, elitist, and protectionist while many (though not all) members of the Paris School were republican, democratic, and laissez-faire in their inclinations. When the February Revolution opened the door to universal (manhood) suffrage the members of the Paris School were dismayed that the expanded franchise was more likely to vote for another Napoléon than they were to vote for free trade.

Rebuilding the Movement

The Restoration of the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences

The rebuilding of the Paris School began with the recreation of the Institute by Louis Philippe in 1832 after its closure in 1803 by Napoléon in order to remove some of his harshest critics like Destutt de Tracy. Members of the Paris School were well represented in the new Institute’s Academy of Moral and Political Sciences which was one of its five branches. The permanent secretary was Charles Comte and members included the following (with the year they were elected): Charles Dunoyer (1832); Joseph Droz (1832); Pellegrino Rossi (1836); Alexis de Tocqueville (1838); Hippolyte Passy (1838); Adolphe Blanqui (1838); Gustave de Beaumont (1841); Léon Faucher (1849); Louis Reybaud (1850); Michel Chevalier (1851); Louis Wolowski (1855); Horace Say (1857); Augustin-Charles Renouard (1861); Henri Baudrillart (1866); Joseph Garnier (1873); Frédéric Passy (1877); Léon Say (1881). Bastiat was made a more junior “corresponding member” in 1846 as was Molinari in 1877.[51]

Teaching Economics

A second innovation was the recognition by the new régime[52] of the discipline of “political economy” as being worthy enough to have its own Chair at the Collège de France.[53] It was created in 1831 and the first appointee was Jean-Baptiste Say who unfortunately did not have time to settle into the new position before he died in November the following year at the age of 65. This sparked a battle to decide upon his successor. The members of the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences supported their own more radical Charles Comte for the position, while the other professors at the Collège supported the more conservative Italian jurist Pellegrino Rossi who eventually got the position.[54] This was unfortunate as Rossi was neither an original thinker in economics nor very radical in his opinions, although he was a strong supporter of free trade.

Rossi held the position from 1833 to 1840 when he was replaced by the free market Saint-Simonian engineer and economist Michel Chevalier who held the post between 1841 and 1852.[55] However, Chevalier’s career showed the precarious situation the economists were in when there we so few academic positions of any kind. Opponents of his free market views within the Provisional Government of the Second Republic had him sacked from his position in April 1848 and divided his chair into several smaller positons which dealt with more “applied economics” which were seen as being more useful for government employed bureaucrats and planners. Only after intense lobbying by the members of the Political Economy Society and their supporters in the National Assembly was Chevalier reappointed to his position in November 1848. Chevalier would make a name for himself as a fierce anti-socialist pamphleteer during 1848–49 and then later as a trusted economic advisor to Louis-Napoléon (Emperor Napoléon III after 1852) who persuaded him to fulfill the dreams of the Paris School by agreeing to sign the first free trade treaty between England and France in 1860, the formal signing of which was done by Richard Cobden for England and Chevalier for France.

There were only two other government funded institutions where members of the Paris School found teaching positons. These were the less prestigious, non-research positions in technical and engineering schools such as the Conservatoire national des Arts et Métiers (the National Conservatory of Technology and Trades) where where J.B. Say had taught “industrial economics” until his death in 1832 and then his replacement Adolphe Blanqui taught from 1833,[56] and the École nationale des Ponts et Chaussées (National School of Bridges and Roads) where Joseph Garnier was appointed a professor of political economy in 1846 when the first chair was established there.

Outside the state system there were a handful of private institutions where economists could teach, or at least give public lectures. Firstly, there was the well-established private lecture forum, the Paris Athénée, where J.B. Say had lectured in 1816–19, Charles Dunoyer 1824–26, Adolphe Blanqui 1827–29, and Joseph Garnier 1842–45. There was also the École Supérieure de Commerce de Paris (The Advanced School of Commerce), which was a private business school which had been co-founded by J.B. Say during the early years of the Restoration. Adolphe Blanqui was appointed director in 1830 and he worked there until his death in 1854. Joseph Garnier also taught there in the 1840s before he took up a position at the École nationale des Ponts et Chaussées. The School of Commerce played a particularly important role in helping establish the careers of two generations of political economists in the Paris School.

The teaching and research prospects for academic economists remained dire until the educational reforms of 1878 which resulted in the professionalisation and insititutionalisation of economics as a academic discipline. Unfortunately, for the members of the Paris School when the government of the new Third Republic decided to expand the teaching of economics they agreed to fund it only within the Law Faculties which required a doctorate in law which none of the economists had, thereby excluding them from the newly created posts. The end result was that economics was often taught by people untrained in economics and not inclined to support laissez-faire views, to students who would become lawyers, bureaucrats, and government officials, who were also disinclined to be receptive to free market ideas.[57]

This problem of the limited supply of teaching and research positions explains why the advent of the Guillaumin publishing firm in 1837 and the satellite associations it spawned afterwards is so important for understanding the growth of the Paris School in the 1840s.

The Guillaumin Network

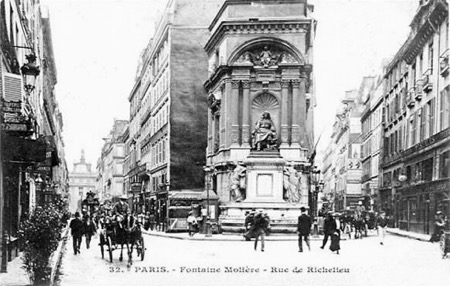

|

| The Molière Fountain on the rue de Richelieu (down the left). The Guiilaumin firm was located at no. 14 rue de Richelieu. |

One of the most important innovations for the consolidation of the Paris School as a serious, organised, and influential intellectual movement came from the entrepreneurial activities of Gilbert-Urbain Guillaumin (1801–1864) who founded the publishing firm which bore his name in 1837.[58] He had become active in politics in the 1820s when he joined the radical democratic and republican Carbonari movement. This may explain his later support for some of the more radical members of the Paris School whose work the firm would later publish, such as Charles Coquelin, Frédéric Bastiat, and Gustave de Molinari, in spite of the objections of many of the more mainstream members of the school. The Guillaumin firm would become the focal point for the Paris School for the next 74 years, channelling money which he helped raise from wealthy benefactors (such as the merchant Horace Say (son of Jean-Baptiste) and the industrialist Casimir Cheuvreux) into the pockets of several generations of liberal political economists. The historian Gérard Minart correctly calls this “le réseau Guillaumin” (the Guillaumin network) given the number of individuals, groups, associations, and activities Guillaumin founded, financed, or put in touch with each other.[59]

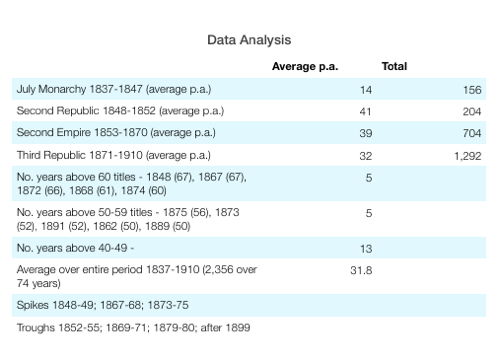

The firm commissioned books on economics (publishing a total of 2,356 titles between 1837 and 1910 at an average rate of 31.8 titles per year),[60] began the Journal des Économistes in December 1841 (it lasted nearly 100 years until the Nazi occupation of Paris in 1940 forced it to close),[61] and the Société d’économie politique in 1842 which became the main organization which brought classical liberals,[62] sympathisers in the intellectual and political elites of France, and foreign visitors together for discussion and debate at their monthly dinner meetings, presided over by the Society’s permanent president Charles Dunoyer.

The publishing strategy of the Guillaumin firm was a sophisticated one which proved to be very successful over many decades. It was designed to attract a broad range of authors as well as readers from different ideological perspectives, not just the hard core of radical laissez-faire advocates. It attracted businessmen with its first commercial success, an Encyclopédie du commerçant. Dictionnaire du commerce et des marchandises (A Dictionary of Commerce and Goods) (1837, 1839, 1841)[63] and other titles dealing with how to buy shares on the stock exchange, bankruptcy law, and trade marks. Its staple was the monthly Journal des Économistes[64] and the annual compendium of statistics and economic data Annuaire de l’économie politique et de la statistique (founded 1844) edited by Guillaumin and Joseph Garnier.[65]

On more theoretical matters, it published in book form the lectures given by Pellegrino Rossi, Michel Chevalier, and Joseph Garnier at the universities and colleges in order to give them a far greater audience. It published dozens of books on economic and financial history, especially on tax, government finance, and pubic credit. It published a steady stream of books dealing with poverty and the social question. A very large academic project it undertook in 1840 was to publish a large collection in 15 volumes of key works in the history of economic thought which was edited by a former tax collector turned editor Eugène Daire (1798–1847) which began by republishing the main works of J.B Say before turning to works on eighteenth-century finance, the physiocrats, Turgot, Adam Smith, Malthus, Ricardo, Hume, and Bentham. This project was notably also for its use of the young generation of rising economists like Alcide Fonteyraud and Gustave de Molinari as editors of some of the volumes, thus giving them much needed income as well as helping them make a name for themselves as scholars.[66]

Finally, they were also keen to demonstrate the new directions in which the Paris School was moving by publishing innovative works by some of the more radical members of the Guillaumin network, such as Coquelin, Du Crédit et des Banques (1848) on free banking, Molinari, Les Soirées de la rue Saint-Lazare (1849) on free market alternatives to public goods provided by the state, Bastiat, Harmonies économiques (1850, 1851), which was his controversial and in part proto-Austrian theoretical treatise,[67] and Ce que l’on voit et ce que l’on ne voit pas ou l’économie politique en une leçon (1850) which was a pioneering work using the idea of opportunity cost to argue against many forms of government expenditure and regulation.

In addition to the publishing firm there were several other groups and organisations which were part of the broader “Guillaumin network” of economists and their friends and allies. These included the French Free Trade Association,[68] the Congrès des Économistes,[69] the Friends of Peace Congress,[70] and the private Paris salons held by Anne Say (née Cheuvreux, the wife of the businessman Horace Say) and Hortense Cheuvreux (the wife the the wealthy textile manufacturer Casimir Cheuvreux).[71]

However, the pinnacle of the Paris School’s achievement in this period was their compendium of “irrefutable” arguments and economic data which would answer all their protectionist, interventionist, and socialist critics - the Dictionnaire de l’économie politique (1852–53).[72] The DEP is a two volume, 1,854 page, double-columned encyclopedia of political economy and is unquestionably one of the most important publishing events in the history of 19th century French classical liberal thought and is unequalled in its scope and comprehensiveness. The aim was to assemble a compendium of the state of knowledge of liberal political economy with articles written by leading economists on key topics, biographies of important historical figures, annotated bibliographies of the most important books in the field, and tables of economic and political statistics. The Economists believed that the events of the 1848 Revolution had shown how poorly understood the principles of economics were among the French public, especially its political and intellectual elites. One of the tasks of the DEP was to rectify this situation with an easily accessible summary of the entire discipline. The major contributors were the editor Charles Coquelin (with 70 major articles), Gustave de Molinari (29), Horace Say (29), Joseph Garnier (28), Ambroise Clément (22), Courcelle-Seneuil (21), and Maurice Block wrote most of the biographical entries. The intellectual ghost floating over the entire project was the recently deceased Frédéric Bastiat. If his health had not been failing rapidly he might have been expected to have played a major role in its production. The editor Coquelin paid homage to him by using large chunks of Bastiat’s essays for two of the key entries in the DEP on “The State” and “The Law.”

Sadly, as the century was coming to a close and as classical liberal ideas were becoming less and less influential, the Guillaumin firm tried to repeat the exercise with an updated version of the DEP in 1891, interestingly edited by Jean-Baptiste Say’s grandson Léon, but with little obvious success in halting the tide of opinion.[73]

Economic and Political (Policy) Issues↑

The economic and political issues the economists had to deal with after 1830 were dominated by the issues of poverty and “the social question” in newly industrialising France, reform of the protectionist system of tariffs and subsidies to industry, and the rise of socialism both as a body of thought as well as an increasingly organised political movement.

Poverty and the Social Question

It is often assumed that the problem of poverty was discovered in the 1830s by religiously inspired social reformers, like Villeneuve-Bargemont’s Économie politique chrétienne (1834), or liberal-minded conservatives, like Tocqueville’s Mémoire sur le paupérisme (1833) who feared state charity would create a permanent underclass of the poor, and by socialists like Louis Blanc’s Organisation du travail (1839) who saw poverty as the proof of the failure of free markets. But this would be incorrect. In should be noted in passing that the future Emperor Napoléon III wrote a pamphlet while in prison, Extinction du Paupérisme (1844), on how to solve the problem of “pauperism” by converting the unused land in France into “agricultural colonies” where labour would be organised along Blanc’s suggestions by “labour marshalls” (“les prudhommes”) who would act as state-financed intermediaries between the workers and the employers.[74]

In the early and mid–1840s the Guillaumin firm published a dozen or so books on this question which indicates their strong interest in the matter, such as d’Esterno, De la Misère, de ses causes, de ses remèdes ((1842); A. Clément, Recherches sur les causes de l’indigence (1846); Théodore Fix, Observations sur l’état des classes ouvrières (1846); and Joseph Garnier, Sur l’association, l’économie politique et la misère (1846), to mention only a few. Where they differed from the social Catholics and the socialists was in the reforms they proposed to solve the problem, not in the fact that they ignored the problem or didn’t take it seriously.

They agreed with the former that there was a need for more charity but only as long as it was charity which was voluntarily given and not “la charité légale” (state funded or “coerced” charity). They agreed with the latter that the current system was broken and did not serve the best interests of the workers, but not that the free market system of wage labour should be abolished and replaced by socialist schemes of industrial “organisation” and labour “associations,” something which would in fact be tried by Louis Blanc in the National Workshops program after February 1848. Instead, they wanted to see all restrictions on the free movement of labour (the right to enter any job or industry without restriction), of capital (the right to set up factories and businesses anywhere and at any time), and of goods (international and domestic free trade) lifted so that all workers could reap the benefits of the division of labour and open markets. One of the things that Chevalier admired most about the United States was the freedom ordinary workers had to mover about the country and enter any occupation they wished without having to seek the permission of the government.[75] He thought that similar freedoms in France would go a long way to solving the social question.

They all agreed, however, in the pessimistic conclusions of Thomas Malthus that excessive population growth led to cut throat competition between workers and thus lower wages, unless they exercised the “moral restraint” required to limit the size of their families. Most members of the Paris School were convinced Malthusians, with Joseph Garnier being the leading Malthusian with several books and articles on his ideas. He edited Guillaumin’s edition of Malthus’s Essai sur le principe de population (1845) and wrote the entries on “Population” and “Malthus” for the DEP (1852).[76] Interestingly, for this the Catholic Church regarded the Economists and the DEP (1852–53) as grossly immoral and had it listed on the Index of Banned Books on 12 June 1856 for “religious reasons.”[77]

One of the few exceptions to this support for Malthus was Bastiat who rejected the idea that the poor were condemned to hovering just above or just below the biological means of subsistence. He preferred to think in terms of the “means of existence” or “standard of living” of a society, which was not a set amount but moved steadily upwards as the economy progressed. The productivity of the free market, if it were unshackled from its protectionist chains and high levels of taxation, would dramatically raise the standard of living of all people, including the poorest. Furthermore, he rejected the idea that mankind’s reproductive behavior was like that of an unthinking plant or an animal (which were subject to Malthusian population traps) but was the result of thinking and reasoning human beings who could adapt their behaviour to changing circumstances. He completely rethought Malthus’ population theory in an an article on "Population” for the JDE (October 1846) and in a revised version in a chapter in Economic Harmonies (the expanded second edition of 1851). He was vigorously challenged by the other members of the Paris School who were unmoved by his arguments and they remained staunch Malthusians for the rest of the century.

Free Trade and Protectionism

The reason the economists were so hostile to tariffs and other subsidies to industry can be reduced to three main points. Firstly, they saw it as a violation of the property rights of producers and consumers, no matter what country they lived or worked in, to buy and sell their goods and services without interference from third parties. To impose a tax or tariff or to prohibit the entry of goods was, in Bastiat’s very direct terminology a form of “legal plunder”[78] and should not be allowed on moral grounds. Secondly, they saw tariffs as just another tax imposed upon the poor, especially on essentials such as food and clothing and, since this is France after all, on wine. It was also a tax imposed on small business owners who ran their own shop or workshop and had to pay taxes on imported raw materials they used to make their own products for sale. Thirdly, they saw the beneficiaries of tariffs and subsidies very much in class terms, where wealthy landowners and industrialists who cloaked their own self-interest in eliminating competitors and increasing their profits in terms of “protecting national labour”, were in fact part of an “oligarchy” or “privileged class” who exploited ordinary consumers for their own benefit.[79] This combination of moral, economic, and political arguments explains the Paris School’s passion in opposing tariffs which they maintained over many decades.

There were three occasions after 1815 when tariff reform was seriously debated in the Chamber of Deputies.[80] The first was in 1821 during the Restoration (discussed above), the second was in 1831–33 soon after the installation of the July Monarchy, and the third was in 1847 on the eve of the 1848 Revolution. Only in the latter case was there a serious chance of any liberalization since the free trade movement which had emerged in 1846 was stronger than it had been at any time previously in the 19th century.

An opportunity for tariff reform presented itself following the poor harvests of 1828–29 and the overthrow of the Bourbon Monarchy in August 1830 which brought to power the July Monarchy of Louis Philippe. Intellectually the classical liberal movement during the 1830s was at a low point since several of them who had come to prominence during the Empire and the Restoration were either quite old or would soon die. The new government commissioned an inquiry into tariff policy in October 1831 with the naval engineer and statistician Charles Dupin (1784–1873) as the head.[81] After five months of deliberation a very lengthy report was produced which was even more protectionist than the government’s original proposal. This was opposed in the Chamber by a small group of free traders who gathered around the journalist and politician Prosper Duvergier de Hauranne (1798–1881),[82] the liberal minded aristocrat Alexandre De Laborde (1773–1842), and François-Eugène, duc d’Harcourt (1786–1865) who later became one of the founders of the Free Trade Association in 1846. The bill was discussed in March 1832 and provisionally adopted until it was made permanent in April 1833. The passage of this bill was a disaster for the depleted and weakened free trade group within the Chamber. The French free trade movement at this time was so weak that the most vigorous response came from an English free trader Thomas Perronet Thompson (1783–1869) who wrote an amusing but thorough critique of the inquiry (in French) called Contre-Enquête: par l’Homme aux Quarante Ecus (A Counter-Inquiry by a Man on 40 Ecus a Year) (1834). This period would have to count as the nadir of the French free trade movement in the first half of the 19th century.

The stimulus for a third attempt at tariff reform came from the activities of the Anti-Corn law League founded in 1838 in Manchester by the manufacturer Richard Cobden and John Bright. Its success in mobilizing popular support for free trade came to the attention of Bastiat in 1844 while he was still living in the relative seclusion of Gascony in the southwest of France. He began subscribing to their journals and other literature and published a lengthy account of their philosophy and most importantly their strategy in Cobden et la Ligue (1845) which erupted like an intellectual bombshell in France. Bastiat wrote a lengthy introduction describing the League’s principles and their critique of British economic policy, translated dozens of speeches and articles by advocates of the free trade position, and described at considerable length how they went about organising a mass movement in favour of free trade, including the important role women played in organising the meetings and handing out literature. Cobden and Bright cleverly made use of the expanded franchise after the 1832 electoral reforms and invented many of the modern methods of organising popular opinion such as collecting signatures to present to politicians, selling merchandise to raise money, organising a travelling band of public speakers who would tour the country talking to large crowds in public halls, and keeping their paid members abreast of affairs with a regular newspaper.

This was the first salvo in a battery of intellectual shells which the new generation of economists lobbed onto the French public between 1845 and 1847 which dramatically changed the debate about tariffs. The salvo included books by the journalist and member of the Chamber of Deputies Léon Faucher (1803–54) who wrote Études sur l’Angleterre (1845) which had two chapters on the Anti-Corn Law League and provided comprehensive background information about the British economy, London, Liverpool and Manchester, and the social and economic reasons behind the rise of Anti-Corn Law League; a series of eight detailed articles by the fluent English speaker Alcide Fonteyraud (1822–1849) who had been sent to England with a letter of introduction to Richard Cobden by Frédéric Bastiat to gather information on the Anti-Corn Law League;[83] the republication by Guillaumin of speeches and essays by an early supporter of free trade in Bordeaux during the 1830s, Henri Fonfrède, Du système prohibitif (1846) possibly in an attempt to show that free trade ideas were not just an English import; the publication of a series of speeches in support of free trade given in the Chambers of Deputies and Peers by the duc d’Harcourt in 1845 and 1846 who was the leading free trader in the Chamber and who became the President of the French Free Trade Association when it was founded in July 1846;[84] a second book on Cobden and the League this time by the economist Joseph Garner in 1846 to follow on from Bastiat’s pioneering work the previous year;[85] a pair of articles by the aging doyen of the Paris School, Charles Dunoyer;[86] and finally Molinari’s comprehensive 2 volume History of Tariffs in 1847 which established his reputation as a serious and rising economist.[87]

Following the success of Bastiat’s and Faucher’s books and the duc d’Harcourt’s speech in the Chamber in 1845, as well as the climax of the British Anti-Corn Law League’s efforts to have the Corn Laws repealed which was announced in the Commons by Sir Robert Peel on January 27 1846, an “Association de la liberté des échanges” (Free Trade Association) was founded in Bordeaux in February 1846 and then a national Association in Paris in July. The duc d’Harcourt was the President of the Association, Bastiat was Secretary General, and Molinari along with Adolphe Blaise, Charles Coquelin, Alcide Fonteyraud, Joseph Garnier were Associate Secretaries, and other founding members and advisors included Michel Chevalier, Auguste Blanqui, and Horace Say. Bastiat wrote the “Statement of Principles” of the Society which contained the radical claim that free trade was a natural right “just like property” which is held by all human beings.[88] The first public meeting of the Paris Association for Free Trade was held in Montesquieu Hall on August 28, 1846 which was the first of a series of public meetings and appeals to the public for support along the lines of the strategy which had been used by the British Anti-Corn Law League. One of their best public speakers was Charles Coquelin who used his deep knowledge of French literature and economic theory to great effect. Another star speaker was the famous poet and politician Alphonse Lamartine who drew very large crowds to hear him deliver his witty and eloquent speeches.[89] As secretary of the Association and editor of its journal Le Libre-Échange Bastiat spent much of 1846 and 1847 travelling all over France giving speeches in Marseilles, Lyon, Bordeaux, and of course Paris.

Many of the articles Bastiat wrote for Le Libre-Échange were collected and republished in two volumes as Economic Sophisms which sold very well for the Guillaumin firm. They were designed for a popular audience and often took the form of a reductio ad absurdum argument where he would take an argument of the protectionists, such as the need to create more work for French workers, which Bastiat suggested could be achieved if the government ordered every French worker to only use their left hand - “The Right Hand and the Left Hand” (LE, 13 Dec. 1846). His most famous “sophism” was the fictional “Petition by the Manufacturers of Candles, etc.” (JDE, October 1845) in which he ridiculed the industrialists who lobbied the government to pass laws to make consumers buy their higher priced goods instead of cheaper imports. In this case, candle manufacturers who wanted the government to pass laws forcing everybody to pull their house shutters closed during the day so they would have to use candles instead of “cheap imported” sunshine to light their homes.

In reaction to the political success of the British free traders and the formation of the French Free Trade Association and its summer campaign a group of northern French industrialists formed their own national “Association pour la Défense du Travail National” (Association for the Defense of National Employment).[90] This had begun as a regional lobby group organized by the textile manufacturer Auguste Mimerel in 1842 in the northern manufacturing city of Roubaix. He and the banker and manufacturer Antoine Odier established the national association in Paris in October 1846 which had as its aim to present themselves as defenders of French labor and employment in the factories rather than as lobbyists for the interests of factory owners. Their journal Le Moniteur industriel was often the butt of Bastiat’s satire and ridicule in the pages of Libre-Échange and the articles which later appeared as Economic Sophisms (1846, 1848). The protectionists were also able to launch a publishing program of their own to defend tariff protection with books by Jules Lebastier, Défense du travail national (1846); Thémistocle Lestisboudois, Économie pratique des nations (1847), and Antoine-Marie Roederer, Les douanes et l’industrie en 1848: dangers et nécessités (1847).