The Conflicted Western Tradition:

Some Provocative Pairings of Texts about Liberty and Power.

Or, “Logos libertas est.”

By David M. Hart

[Created: 24 March, 2019]

[Revised: 29 March, 2025] |

Introduction

This paper was presented at the Association of Core Texts and Cources 25th Annual Conference 2019: “Logos: Here And There, Now And Then”, Thursday, April 11 – Sunday, April 14, 2019, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Conference Theme: “Logos: Here And There, Now And Then”

ACTC invites paper and panel proposals that envision — by thematic content, by juxtaposition of works, and by the spirit and approach of the inquiry —paths to reasoned, civil discourse across differences of all kinds, ways in which we can be shocked by the familiar where we might least expect it, and encounters with texts beyond our immediate horizons with old and new modes of discovery. [my emphasis]

Abstract

A common criticism of the teaching of core texts of the western tradition is that it “privileges” one civilisation over another, and that it favors one group of people or one way of thinking over others. Yet it seems clear that “the” western tradition is better understood as a collection of contending and conflicted traditions which have been battling it out intellectually for over 2,000 years. The idea of “liberty” has been one of these hotly contested sub-traditions within the broader “western tradition” (strong vs. weak state, centralized vs. dispersed power, free markets vs. government regulation and planning, “capitalism” vs. “socialism”, individualism vs. “community”). A more careful selection of texts in which contemporary texts with radically different notions of individual and economic liberty can be paired in a provocative way in order to bring out the ongoing conflicted nature of “western” thinking about the power of the state, the rights and liberties of individuals, the right of resistance to authority which oversteps its bounds, and the best way to bring about peace and prosperity. Thus, in the words of the Conference them: “logos libertas est.”

The Conflicted Western Tradition: Some Provocative Pairings of Texts about Liberty. Or, “Logos libertas est.”

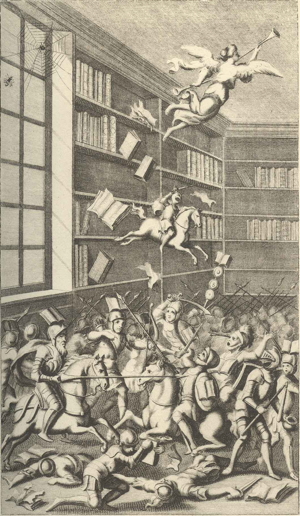

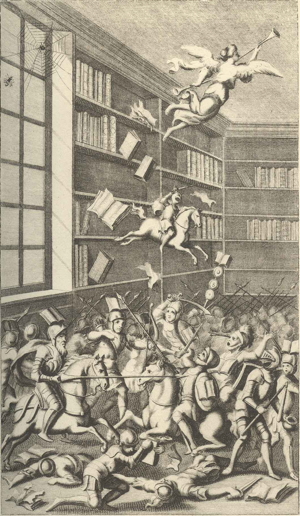

Another “Battle of the Books”

|

| Jonathan Swift, The Battle of the Books (1704) |

Introduction to the “Conflicted” Western Tradition

A common criticism of the teaching of core texts of the western tradition (WT) is that it “privileges” one civilisation over another, and that it favors one group of people or one way of thinking over others. A good recent example of this is the opposition by academics in Australia to the newly founded Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation Online elsewhere in Sydney.

The Ramsay Centre

The Ramsay Centre (“RC”, founded March 2017) is funded by an endowment created by the Australian billionaire hospital magnate Paul Ramsay (1936-2014) who wanted to promote the teaching and understanding of the WT by funding courses in existing Australian universities (nearly all of which are government funded) and granting lucrative scholarships to the students who were admitted to the courses. Australia, unlike the U.S., lacks a tradition of teaching coherent programs in the WT or the Great Books and so the RC’s program was innovative and provocative. Most of the opposition centred around the idea that by teaching courses on the WT the RC thought the WT was “better” than other civilisations (which some of its supporters no doubt did) and that any university which accepted RC money would be giving “favored treatment” to this tradition over others (in spite of the fact that several Australian universities were happy to host Chinese government funded Confucius Institutes). Only after a struggle of nearly two years has one smaller Australian university (the University of Wollongong, south of Sydney) accepted the RC’s offer and is now building such a program which will open in 2020.

Competing Sub-Traditions within the WT

Part of the problem in my view, is that both sides have misunderstood what “the WT” really is. First of all, it is not a single tradition, but many conflicting and interwoven traditions, or sub-traditions if you like. Secondly, it is not ”conservative” (whatever that might mean) but has always had a “radical” component as well. Some of the supporters of the RC have argued that the WT has given the modern world Christianity, individual liberty, constitutional government, rule of law, prosperity, and critical thinking (which of course it has, by and large). Its opponents have argued that the WT has given us colonialism, patriarchy, racism, slavery, and economic exploitation (which to some degree it has as well).

It seems clear to me that “the” western tradition is better understood as a collection of contending and conflicted “sub-traditions” which have been battling it out intellectually for over 2,000 years with no apparent end in sight. Thus, to give another example, one could say (and many have done so) that “the West” is Christian and point to the work of Saint Paul, Thomas Aquinas, Luther, among many; whereas one can also point to a long and persistent thread of materialist and secular thinking going back to Lucretius and forward to Charles Darwin and modern science, to argue the opposite. In the Middle Ages Christianity was the dominant tradition; today one might argue that non-religious materialism has become the dominant view. And both perspectives would be correct, or partly correct.

The Sub-tradition of “Liberty vs. Power” in the WT

Yet another example are those who have argued that WC is about the “ceaseless struggle for liberty” like Ludwig von Mises and Lord Acton. The Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises, whose views have greatly influenced my own thinking about politics and economic theory, believed that “liberty” itself was the product of WC. In an article he wrote in 1950 on “The Idea of Liberty is Western” he argued that: [1]

The history of civilization is the record of a ceaseless struggle for liberty. …

The idea of liberty is and has always been peculiar to the West.

What separates East and West is first of all the fact that the peoples of the East never conceived the idea of liberty. The imperishable glory of the ancient Greeks was that they were the first to grasp the meaning and significance of institutions warranting liberty…

Also in the countries of Western civilization there have always been advocates of tyranny — the absolute arbitrary rule of an autocrat or an aristocracy on the one hand and the subjection of all other people on the other hand. But in the Age of Enlightenment the voices of these opponents became thinner and thinner. The cause of liberty prevailed. …

One can also see this line of thinking in the work of Lord Acton who had intended but never was able to finish a monumental “History of Liberty.” In one of his unpublished manuscripts he wrote that the idea of liberty is “the unity, the only unity, of the history of the world, and the one principle of a philosophy of history.” [2]

To a large degree I share the perspective of Acton and Mises but I would modify it somewhat by saying that the idea of “liberty” and the related idea of the power of the state is just one of several hotly contested and conflicted “sub-traditions” within the broader WT. Thus we have had and still do today debates which rage about the need for a strong vs. a weak state, centralized vs. dispersed power, free markets vs. government regulation and planning, or more crudely “capitalism” vs. “socialism.” So what then does “the WT” have to say about the ideal size and power of the state? It all depends upon whom you read, when they wrote their book, and with whom they were arguing.

Liberty Fund and Conversations about the “Great Books about Liberty”

The organisation I work for, Liberty Fund, was founded to promote discussion of “the Great Books about Liberty” (GBL) [see Online elsewhere for a list] by means of “conversations” and Socratic discussions of a large number of core texts about liberty and power spanning at least two thousand years. Back in the 1950s Pierre Goodrich, a successful Indiana lawyer and businessman, worked with Mortimer Adler and others at the University of Chicago on developing the Great Books program. [3] Liberty Fund was founded in 1960 partly as a consequence of these discussions and activities. Goodrich had his own “list” of the Great Books and decided to go his own way with Liberty Fund and his support for Wabash College, where he built an impressive Seminar Room in the Lily Library on the campus. [4]

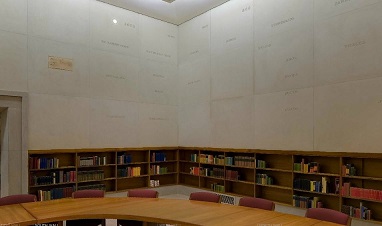

|

| [the Goodrich Seminar Room in the Lily Library at Wabash College, IN] |

This Seminar Room was designed as a place where socratic discussions about the texts could take place with the names of his favorite authors engraved on the impressive limestone walls which surrounded a very large oval table around which the discussants sat. LF’s new building in Indianapolis has the same names emblazoned on its metal facade which faces a major road so the passing motorists can be inspired by the likes of Smith, Hume, and Aristotle; not to mention Hammurabi. Who knows what the local Hoosiers driving past think of that, if they notice at all.

|

| [the facade of LF’s new building in Indianapolis, IN.] |

Fifty eight years later LF is still pursuing our founder’s goal to encourage discussion of these GBL both in face-to-face socratic discussion at the over 100 conferences for academics we organise each year, as well as online with the Online Library of Liberty’s “Liberty Matters Online Discussion Forum,” [5] and the 1,500 or so texts we also have online and make available free of charge to the public.

What we have learned from these discussions, or “conversations” as we like to call them, is that they work best when people disagree, when a variety of interpretations are brought to the table, and a spirited and civil discourse ensues (punctuated with good food and wine, as our founder instructed, to facilitate the conversation). Another thing that we have learned is that the pairing of readings with contrasting or even opposing views can lead to the most interesting discussions. What we are doing here is revelling in the fact that the WT is deeply conflicted on these issues, both then and now, and that the conversation about them is still ongoing and unresolved, that we can learn from similar debates in the past, and add our new perspectives, and move the discussion to a new and hopefully more informed level.

“Provocative Pairings” of Great Books about Liberty at the Online Library of Liberty

What I have spent much time doing at the OLL is drawing up lists of “provocative pairings” of texts, or “Debates” as I also call them, [6] in order to bring out these conflicting sub-traditions within the WT in order to provoke interesting discussions. I try to find contemporary texts with radically different notions of individual liberty and state power in order to bring out the conflicted nature of “western” thinking about the power of the state, the rights and liberties of individuals, the right of resistance to authority which oversteps its bounds, and the best way to limit state power and to keep it with bounds.

This links up quite nicely with the Conference Theme which states that ACTC invites:

proposals that envision — by thematic content, by juxtaposition of works, and by the spirit and approach of the inquiry — paths to reasoned, civil discourse across differences of all kinds, ways in which we can be shocked by the familiar where we might least expect it, and encounters with texts beyond our immediate horizons with old and new modes of discovery. [my emphasis]

It is my hope that my “provocative pairings” or “juxtapositions” of texts might be of interest to others to try in their own teaching at the college level. The pairings are designed to get the reader shocked by the familiar by contrasting a classic work with a contemporary opposing text; and to encourage people to read texts beyond our immediate horizons by introducing less well-known texts which in some cases deserve to become “classics” in their own right.

It is also my hope to show the critics of “the” WT that this tradition is and never was monolithic, that the issues raised by the texts have not been resolved, and ideas and discussions from the past can inform our own discussions in the present concerning similar or related issues.

In each instance, I have also tried to find a text which most people in the Core Texts or GB tradition would regard as “classic” and pair it with a radically different, perhaps lesser known text, which reveals that there were different ways of thinking about the issue even at the time the “classic” text was written. I have done this with primarily political and economic texts, but something similar I’m sure could be done with works of art, philosophy, and literature.

The three examples I have chosen to illustrate this approach here are Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651), Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776), and Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto (1848).

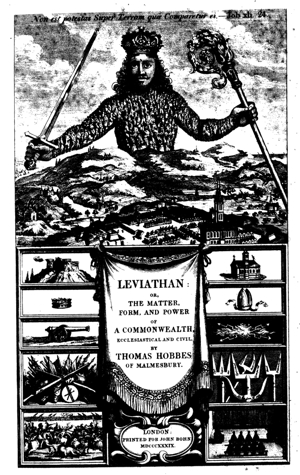

Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651)

|

|

| Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) | Frontispiece to Leviathan (1651) with symbols of "throne" and "altar" |

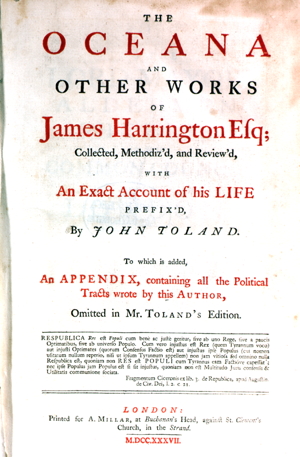

So, to go with Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651) [7] you could use a contemporary almost utopian vision of The Commonwealth of Oceana (1656) by James Harrington [8] which was a thinly veiled depiction of the ideal republic which might have emerged as a result of the English Civil Wars and revolution of the late 1640s. Whereas Hobbes defended the dictatorship of absolute, divine monarchy, Harrington was dabbling with ideas of democracy and republicanism and his work would have some influence on ideas about government which emerged later in 18th century north America.

|

|

| James Harrington (1611-1677) | Title Page of John Toland's 1737 ed. of Oceana (1656) |

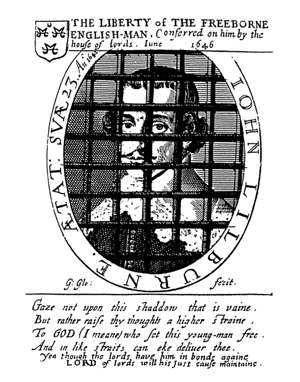

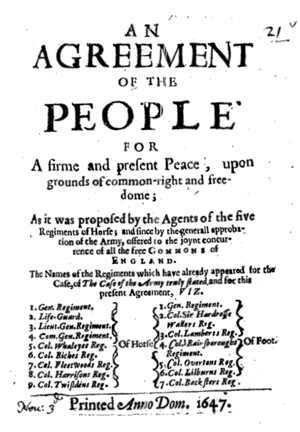

Or if you wanted to be even bolder, you could pair it with some of the radical, proto-classical liberal ideas of the so-called Levellers like Richard Overton and John Lilburne who wrote some of the first modern constitutional documents known as “Agreements of the People” [9] between 1647-49 which contained quite radical notions of representative government, broad (although limited to most but not all males) franchise, very strict limits on government power, and nearly anarchistic rights to overthrow any governments which transgressed these limited powers. See especially “The First Agreement of the People (3 Nov. 1647),” or Richard Overton’s powerful anti-authoritarian tract An Arrow against all Tyrants (1646). [10]

|

|

| John Lilburne (1615-1657) | Title Page of Pamphlet |

They could not be more different from the ideas of their contemporary Thomas Hobbes.

Or there is the more philosophical criticism provided by Richard Cumberland’s A Treatise of the Laws of Nature (1672) who took Hobbes to task for his atheistic and absolutist interpretation of natural law, arguing instead that natural law was in fact based upon man’s natural sociability and that it it imposed obligations on people including the ruler. [11]

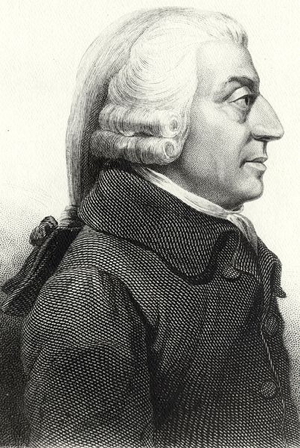

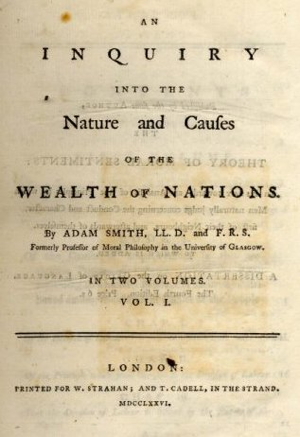

Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776)

|

|

| Adam Smith (1723-1790) | Title page of 1st ed. |

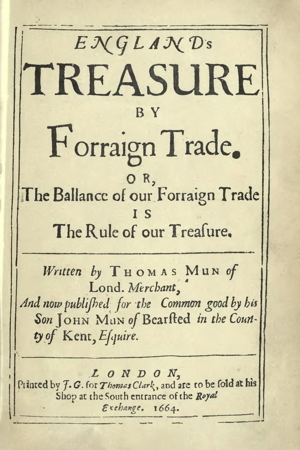

My second example, is a text to be paired with Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776). [12] It is rightly regarded as one of the foundational texts of modern economics and the idea of free trade and free markets. Much less known are the previous authors and texts of the mercantilist school (i.e. trade protection in order to maintain a positive “balance of trade” for the country and thus a net inflow of bullion (gold)) which he spent so much time rebutting in WoN. If the reader does not know who and what these authors and texts were, Smith’s attack has much less meaning. The only consolation perhaps, is that these 17th and 18th century mercantilist or protectionist ideas persisted well into the 19th century (Friedrich List) and in own time (Donald Trump) so their ideas are not completely unfamiliar to the modern reader. However the standard defense of mercantilism and trade protection was by Thomas Mun, England’s Treasure by Forraign Trade (1644) whose tract is the one I have chosen to go with Smith. [13]

|

|

| Thomas Mun (1571-1641) | Title Page |

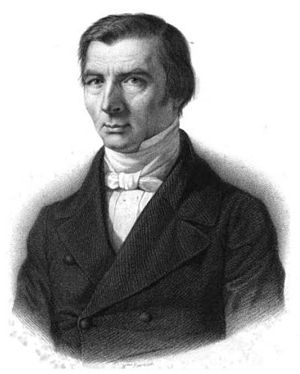

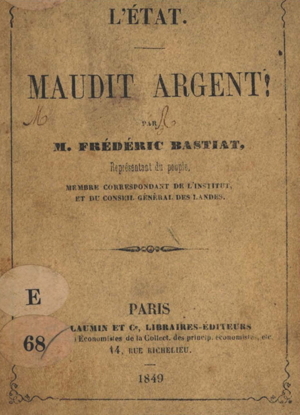

You could have a very similar pairing of less well-known, and thus not (yet) “classic,” texts from the 1840s with the German nationalist and protectionist economist Friedrich List whose ideas, in Das National System der politischen Oekonomie (The National System of Political Economy) (1841), [14] laid the foundation stone for the modern version of protectionism (such as the need to protect and subsidize “infant industries” in order for the modern nation state to be strong economically and thus militarily); placed against a French economist who was writing half a dozen years later. Frédéric Bastiat’s anti-protectionist free trade writings, like the several collections of Sophismes Économiques (Economic Sophisms) (1846, 1848) have reached the status of a “classic” among some circles in the United States. [15] He also happens to be the greatest economic journalist who ever lived and students find his writings funny, clever, and very approachable even if they know no economics.

Both of these pairings are very clear examples of how some late 18th and mid-19th century debates are almost identical to the ones going on today about free trade and protection, and how they are “timeless” in a sense.

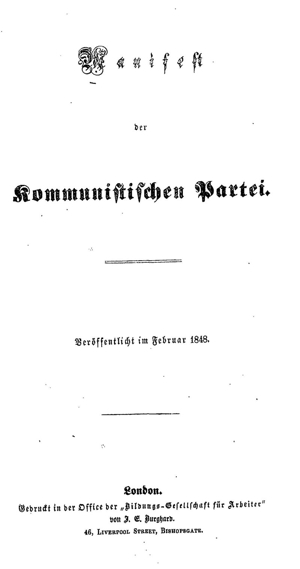

Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto (1848)

|

|

| Karl Marx (1818-1883) | Title page of Manifesto |

Everybody knows Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto (1848), [16] especially given the coverage he got, even in newspapers like the NYT, last year which was the bicentennial year of his birth. [17] Again I would pair this with his contemporary Frédéric Bastiat, who, as I have argued elsewhere, in some ways was “the Karl Marx of the classical liberal movement.” Marx and Engels had written the Manifesto in late 1847 and had gone to Paris to distribute it among the ex-patriot German workers during the early weeks of the February Revolution in one of the political clubs which sprang up once censorship collapsed (“le Club des Travailleurs allemands” (the German Workers Club)). The Manifesto has some of Marx’s best journalism, a clear statement of his theory of class and the evolution of societies through different economic stages, the inevitable end-crisis of capitalism, a list of demands to reform society in a socialist direction (a list very similar to the things the new welfare states enacted in Europe following the end of WW2), and some very, very bad economics (such as the labour theory of value). Bastiat was also in Paris at the time and was involved in the revolution, getting elected to the new Constituent Assembly of the Second Republic. He too participated in one of the political clubs, the “Club de la Liberté du Travail” (the Club for the Liberty of Working) and could easily have met Marx, but didn’t to my knowledge. A few months later he wrote one of the classic criticisms of socialism and the redistributive state in a pamphlet simply called “L’État” (The State) (June and Sept. 1848), in which he defined the state as: [18]

L’Etat, c’est la grande fiction à travers laquelle tout le monde s’efforce de vivre aux dépens de tout le monde |

The state is the great fiction by which everyone endeavors to live at the expense of everyone else. |

|

|

| Frédéric Bastiat (18101-1850) | Title page of Pamphlet version of “The State” |

The contrasts between Marx’s view of the state and Bastiat’s could not be greater and the two thinkers laid out rival theories of politics (limited state power protecting the liberty and property of all individuals vs. the state controlling everything in the name of the working class) and economics ( laissez-faire non-intervention in the economy vs. state ownership or control of nearly every aspect of the economy) the pro and cons of which have been argued about ever since, and have even resurfaced again today.

Conclusion: More of the Same but different

This methodology also leaves the door open to using a modern text (or non-western text) as the contrasting text to the “classic” work in order to bring out the different (or not so different) ways there are of thinking about key issues. This practice might also assuage the concerns of the “traditionalists” that the GB are no longer being read, and the “modernists” or “radicals” that alternative perspectives (whether old or new) are being ignored.

Nineteen Examples of “Provocative Pairings” of Texts, or a new “Battle of the Books”

|

| Jonathan Swift, The Battle of the Books (1704) |

It is not my purpose in this paper to provide the usual brief discussion of a single core text and provide a dazzlingly new interpretation. Rather, it is to suggest a new way of thinking about the pedagogy of teaching core texts in the WT. The following collection of 19 “provocative pairings” spans the early 16th century and goes up to the end of WW2.

- Machiavelli, The Prince (1513) vs. Desiderius Erasmus, The Education of a Christian Prince (1515)

- Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (1651) vs. James Harrington, The Commonwealth of Oceana (1656)

- Sir Robert Filmer, Patriarcha, or the Natural Power of Kings (1680) vs. John Locke, The Two Treatises of Civil Government (1689)

- Montesquieu, Spirit of Laws (1748) vs. Destutt de Tracy, A Commentary and Review of Montesquieu’s ’Spirit of Laws’ (1806)

- Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) vs J.-J. Rousseau Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (1754) and The Social Contract (1762)

- Beccaria, An Essay on Crimes and Punishments (1764) vs. Bentham, Panopticon, or the Inspection-House (1787)

- Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (1776) vs. Thomas Mun, England’s Treasure by Forraign Trade; or, the Ballance of our Forraign Trade is the Rule of our Treasure (1644)

- Edmund Burke, Reflections on the French Revolution (1790) vs. Thomas Paine, Rights of Man (1791)

- Thomas Malthus, An Essay on Population (1798, 1826) vs. William Godwin, Of Population (1820)

- Friedrich List, Das National System der politischen Oekonomie (The National System of Political Economy) (1841) vs. Frédéric Bastiat, Sophismes Économiques (Economic Sophisms) (1846, 1848)

- Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto (1848) vs. Frédéric Bastiat, The State (1848)

- John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1859) vs. James Fitzjames Stephen, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity (1874)

- Karl Marx, Das Kapital vol. 1 (1867) vs. Frédéric Bastiat, Economic Harmonies (1851) or John Stuart Mill, Principles of Political Economy (1848)

- John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism (1861) vs. Herbert Spencer, Social Statics (1851) or The Principles of Ethics (1879)

- George Bernard Shaw, Fabian Essays in Socialism (1889) vs. Thomas Mackay, A Plea for Liberty: An Argument against Socialism and Socialistic Legislation (1891)

- Edward Bellamy, Looking Backward: 2000–1887 (1888) vs. Eugen Richter, Pictures of the Socialist Future (1893)

- Lenin, The State and Revolution (Aug.-Sept. 1917) vs. Ludwig von Mises, “Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth“ (1920) and Socialism (1922)

- Ludwig von Mises, Nation, State, and Economy (1919) vs. Carl Schmitt on Dictatorship (1921), Political Theology (1922), and The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy (1923)

- The Beveridge Report (Social Insurance and Allied Services) (1942) vs. Friedrich Hayek, The Road to Serfdom (1944)

1. Machiavelli, The Prince (1513) vs. Desiderius Erasmus, The Education of a Christian Prince (1515)

Here are two very different pieces of advice to a “prince”, i.e. any ruler of a country. [19] Machiavelli says that the ruler should rule as ruthlessly as necessary to stay in power, and the purpose of rulership is to further the interests of those in power and the state itself. Erasmus argues that the Prince should rule according to some higher moral code which applies equally to all subjects (in this case Christianity) and that the ruler should do everything in his power to protect the interests of the people. Interestingly, both Machiavelli and Erasmus also wrote on the role of war in gaining and keeping power and the impact war had on ordinary people.

2. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (1651) vs. either, James Harrington, The Commonwealth of Oceana (1656) , or some Leveller Tracts by Richard Overton and John Lilburne in the late 1640s, or Richard Cumberland), A Treatise of the Laws of Nature (1672)

One could use several texts in opposition to Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651). [20] The most philosophical is Cumberland’s A Treatise of the Laws of Nature (1672) [21] who took Hobbes to task for his atheistic and absolutist interpretation of natural law, arguing instead that natural law was in fact based upon man’s natural sociability and that it imposed obligations on all people including the ruler.

A second text is Harrington’s The Commonwealth of Oceana (1656) [22] which was a thinly veiled depiction of the ideal republic which might have emerged as a result of the English Civil Wars and revolution of the late 1640s. Whereas Hobbes defended the dictatorship of absolute, divine monarchy, Harrington was dabbling with ideas of democracy and republicanism and his work would have some influence on ideas about government which emerged later in 18th century north America.

A third text or group of texts are more political in nature, such as the radical, proto-classical liberal ideas of the so-called Levellers like Richard Overton and John Lilburne who wrote some of the first modern constitutional documents known as “Agreements of the People” between 1647-49. [23] These contained quite radical notions of representative government, broad (although limited to most but not all males) franchise, very strict limits on government power, and nearly anarchistic rights to overthrow any governments which transgressed these limited powers. See especially “The First Agreement of the People (3 Nov. 1647).” Or Richard Overton’s powerful An Arrow against all Tyrants (1646). [24]

3. Sir Robert Filmer, Patriarcha, or the Natural Power of Kings (1680) vs. John Locke, The Two Treatises of Civil Government (1689) or James Tyrrell’s Patriarcha non monarcha. The Patriarch unmonarch’d (1681)

Filmer’s defence of the divine right of kings, Patriarcha, or the Natural Power of Kings (1680), [25] is based on the notion that legitimate monarchy can trace its ancestry back to Adam and the sons of Adam, and is thus divine in origin and thus unchallengeable by mere mortals. This line of argument explains the great detail Locke goes into in the First Treatise of Government (1689). [26]

A similar contemporary text one might use is James Tyrrell’s Patriarcha non monarcha. The Patriarch unmonarch’d (1681) [27] in which there is much discussion about the power of the husband over his wife and servants and to what extent these powers are applicable to a monarch who claims similar rights over his subjects.

4. Montesquieu, Spirit of Laws (1748) vs. Destutt de Tracy, A Commentary and Review of Montesquieu’s ’Spirit of Laws’ (1806)

The appearance of Montesquieu’s Spirit of Laws [28] in 1748 provoked a debate which has raged ever since. Montesquieu anaysed different forms of government, the impact of climate on social organization, advocated the separation of powers as a brake on the power of the monarch, and espoused unorthodox religious views (thus getting his book placed on the Index in 1751). Destutt de Tracy [29] took issue with many of Montesquieu’s ideas and Thomas Jefferson was so interested in his ideas that his book was translated and published by Thomas Jefferson during his retirement from politics.

5. Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) vs J.-J. Rousseau Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (1754) and The Social Contract (1762)

We have here two very contrasting analyses of the impact of the civilizing process on individuals - a very pessimistic one by Rousseau who thought civilisation had a corrupting influence on people who were happier in a state of nature; [30] and the optimistic view of Smith that individuals learnt to be polite, respectful, law-abiding citizens partly thorough their innate sense of “sympathy” they felt towards others like themselves, and partly from their self-interest, since living in society surrounded by others enabled them to experience the benefits of the division of labour and free trade. [31]

Another striking difference in their views is that Rousseau thought that societies needed to guided by a wise and far-seeing “Legislator” who would create the legal, political, and economic foundations of society and guide men to act in their own interests since they were largely incapable of doing that for themselves. Smith, on the other hand, developed the idea of the “invisible hand” (introduced in his Wealth of Nations), by which he meant that men could be left alone to pursue their own self-interests without outside government since, in order to benefit themselves by buying and selling in the market (i.e. making profits), they first had to serve the interests of their fellows by producing things their fellows wanted to buy.

6. Beccaria, An Essay on Crimes and Punishments (1764) vs. Bentham, Panopticon, or the Inspection-House (1787)

Judicial and legal reform was a key issue for thinkers during the Enlightenment who wanted to reform the brutal and often draconian system of punishments all European countries imposed on “criminals.” One of the main concerns was that punishments should be proportional to the crimes committed and that draconian punishments like execution be only used for very serious and not minor crimes. The Italian legal philosopher, political economist and politician Cesare Bonesana di Beccari (1738-1794) went even further in advocating an end to torture and the death penalty. [32]

Another legal reformer was the lawyer and theorist of utilitarianism Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) who was very interested in prison reform based upon his ideas about utilitarianism and the pleasure/pain principle which is used to induce people to change their behaviour. His idea of a new prison system based upon the constant inspection of inmates, the “Panopticon; Or, the Inspection-House” (1787), [33] was intended to be more humane but many enlightened reformers regarded it as just another kind of torture.

7. Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (1776) vs. Thomas Mun, England’s Treasure by Forraign Trade; or, the Ballance of our Forraign Trade is the Rule of our Treasure (1644)

Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776) [34] is rightly regarded as one of the foundational texts of modern economics and the idea of free trade and free markets. He was writing to oppose the mercantilist school which argued that trade protection (tariffs, import bans) were necessary in order to maintain a positive “balance of trade” for the country and thus a net inflow of bullion (gold). The standard defense of mercantilism and trade protection was by Thomas Mun, England’s Treasure by Forraign Trade (1644). [35]

8. Edmund Burke, Reflections on the French Revolution (1790) vs. Thomas Paine, Rights of Man (1791)

The publication of Richard Price’s sermon on “A Discourse on the Love of Our Country” in November 1789, [36] in which he praised both the American and the French Revolutions, prompted Edmund Burke to write his critique of the French Revolution Reflections on the Revolution in France in 1790. [37] This began a debate about the nature of the French Revolution which continues to this day: was it a step towards individual liberty and constitutional government or towards chaos and tyranny? Burke’s critique was quickly replied to by supporters of the Revolution such as Thomas Paine (1791) [38] and William Godwin (1793). [39] Burke, in turn, returned to the topic in numerous other writings.

Women also participated in this discussion about the impact of the French Revolution with both Catharine Macaulay [40] and Mary Wollstonecraft supporting it against Burke’s criticisms. Wollstonescraft is also noteworthy for extrapolating from the “rights of man” (the subject of her first book” to the “rights of woman” in her second. [41]

9. Thomas Malthus, An Essay on Population (1798, 1826) vs. William Godwin, Of Population (1820)

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries a debate arose over the impact that rapidly increasing population would have on the standard of living. The pessimistic school, represented by Malthus, [42] argued that population would inevitably increase at a geometric rate, whilst agricultural output would only increase arithmetically. Thus, the standard of living of ordinary people would suffer unless they practised some kind of family planning and restraint. The optimists, many of whom were free market economists or political theorists like William Godwin, [43] argued that human ingenuity, more scientific agricultural practices, and efficiencies of the free market would cope with expanding populations and that, in fact, life would get much better for ordinary people.

10. Friedrich List, Das National System der politischen Oekonomie (The National System of Political Economy) (1841) vs. Frédéric Bastiat, Sophismes Économiques (Economic Sophisms) (1846, 1848)

A 19th century pairing of a classic defence of protectionism and a defender of free trade. The German nationalist and protectionist economist Friedrich List [44] laid the foundation stone for the modern version of protectionism, such as the need to protect and subsidize “infant industries” in order for the modern nation state to be strong economically and thus militarily. This was opposed by Frédéric Bastiat, [45] the anti-protectionist free trader, who wrote some of the greatest economic journalism ever written. His writings attacking and mocking protectionism are funny, clever, and very approachable even for those who know no economics.

11. Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto (1848) vs. Frédéric Bastiat, The State (1848)

The Manifesto has some of Marx’s best journalism, [46] a clear statement of his theory of class and the evolution of societies through different economic stages, the inevitable end-crisis of capitalism, a list of demands to reform society in a socialist direction (a list very similar to the things the new welfare states enacted in Europe following the end of WW2), and some very, very bad economics (such as the labour theory of value). Bastiat [47] wrote a series of pamphlets attacking socialism on the grounds of its violation of individual rights to liberty and property, and the economic irrationality of its program.

12. John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1859) vs. James Fitzjames Stephen, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity (1874)

John Stuart Mill has a controversial place in the classical liberal tradition. He shocked many conservatives with his support for women’s suffrage in The Subjection of Women (1869) and seemed to justify considerable state intervention in the economy in his Principles of Political Economy (1848). One of his most influential books, On Liberty (1859), [48] prompted a critique by Stephen [49] who argued that Mill’s idea of liberty and equality undermined the older liberal notions of “ordered liberty” and “equality under law”. Stephen criticized Mill for turning abstract doctrines of the French Revolution into “the creed of a religion.” Only the constraints of morality and law make liberty possible, warned Stephen, and attempts to impose unlimited freedom, material equality, and an indiscriminate love of humanity will lead inevitably to coercion and tyranny.

13. Karl Marx, Das Kapital vol. 1 (1867) vs. Frédéric Bastiat, Economic Harmonies (1851) or John Stuart Mill, Principles of Political Economy (1848)

The recognized pinnacle of the classical school of economics (Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Thomas Malthus) was J.S. Mill’s Principles of Political Economy (1848) [50] with its concern for economic growth, free trade, the productivity of the free market, the profit system, the danger of over-population, and a general presumption in favour of laissez-faire government policy.

Criticism of the classical school came from two different directions - from the socialists and Marxists, and from other free market economists who wrote later in the century. Karl Marx provided the most detailed critique in his multi-volume work Das Kapital (Capital) (1867, 1885, 1894). [51] Marx prided himself on having discovered the “laws” which governed the operation of the capitalist system, laws which would inevitably lead to its collapse. He believed in the labour theory of value (that things had value because of the amount of labour expanded in creating them), that the payment of wages to workers by their employer was inherently exploitative because the worker did not receive the “full value” of the work, that workers’s wages would tend to fall to the absolute minimum required to keep them alive and reproduce, that capitalist businesses would increasingly become less profitable as competition reduced what they could receive for their products, and that the system would be inevitably overthrown by an uprising of the organized exported workers.

Defenders of the “capitalist system” like the French economist Frédéric Bastiat argued the exact opposite to Marx on nearly every matter: that things had value because of the subjective value people (consumers) placed on their regardless of how much labour was used to make them, that wages were a voluntary agreement reached between empty and worker in which both parties benefited, that workers’s wages would rise as more capital was invested in machinery and as the division of labour deepened, that capitalists would find ever more needs consumers wanted satisfied and would continue to grow and be profitable, and that the system only malfunctioned because governments interfered with the operation of the otherwise “harmonious” free market. Bastiat wrote a series of witty but deeply insight anti-socialist pamphlets between 1848 and 1850, and left an unfinished treatise on economics with a radically new defense of free market economics, Economic Harmonies (1850, 1851). [52]

14. John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism (1861) vs. Herbert Spencer, Social Statics (1851) or The Principles of Ethics (1879)

Within classical liberalism there was a division between two different ways of justifying individual liberty and a limited government. The older, more traditional way was to ground the defence of liberty on natural law, which was a tradition which went back to the ancient Greeks and Romans, and which had a revival in the 17th century (most notably with John Locke’s defence of liberty in his Two Treatises of Government). One of the best defenders of the natural rights approach in the 19th century was the English theorist Herbert Spencer who wrote an early work, Social Statics (1851), [53] in which he developed his idea of justice and “the law of equal freedom” which stated that “every man has freedom to do all that he wills, provided he infringes not the equal freedom of any other man.” [54] He expanded his ideas in a later work The Principles of Ethics (1879). [55]

In contrast, or even opposition, to this tradition was the “utilitarian” or “Benthamite” tradition which rejected natural law and natural rights as “nonsense” and argued that one should judge what the government should or should not do on whether or not it pursued “the greatest good of the greatest number” of people. In other words, on the grounds of “utility” or usefulness and not on individual “rights.” This line of thinking was developed by Jeremy Bentham, James Mill, and John Stuart Mill, and eventually became the dominant form of liberalism by the late 19th century. J.S. Mill’s defense of Utilitarianism [56] came nearly midway between Spencer’s two works.

15. George Bernard Shaw, Fabian Essays in Socialism (1889) vs. Thomas Mackay, A Plea for Liberty: An Argument against Socialism and Socialistic Legislation (1891)

In the late 19th century the classical liberal, free market orthodoxy was beginning to be challenged by socialists like George Bernard Shaw, [57] who put together a collection of essays in 1889 advocating greater intervention by the state in the economy. Unlike the Marxists, who desired revolutionary change, the “Fabian socialists” advocated incremental change through the parliamentary system and would have considerable success in Britain and Australia, leading eventually to the formation of the modern welfare state after 1945. This volume provoked a reply by supporters of private property and laissez-faire economics led by Thomas Mackay. [58]

16. Edward Bellamy, Looking Backward: 2000-1887 (1888) vs. Eugen Richter, Pictures of the Socialist Future (1893)

The American socialist Bellamy [59] wrote a utopian novel about a man who fell asleep in 1887 and woke up in an American socialist paradise in 2000 where people lived in complete harmony since economic competition had been abolished, the state owned all property and thus controlled and planned every economic activity, and there was abundance for all. The German classical liberal political Richter [60] wrote a dystopian novel in 1893 about what would happen to Germany if the socialism espoused by the trade unionists, social democrats, and Marxists was actually put into practice. He argued that that government ownership of the means of production and centralised planning of the economy would not lead to abundance as the socialists predicted would happen when capitalist “inefficiency and waste” were “abolished”. The problem of incentives in the absence of profits, the free rider problem, the public choice insight about the vested interests of bureaucrats and politicians, the connection between economic liberty and political liberty, were all wittily addressed by Richter.

17. Lenin, The State and Revolution (Aug.-Sept. 1917) vs. Ludwig von Mises, “Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth“ (1920) and Socialism (1922)

Neither Marx nor any other late 19th or early 20th century Marxist thinker gave much thought to how a centrally planned communist economy would operate once all “the means of production” had been taken from their private owners and run by the state, and wage labour and free market pricing for goods, services, and capital had been abolished. On the eve of the October 1917 Revolution Lenin began thinking about this problem and his only solution was to model running the entire economy on the way the state had run the Post Office. [61] The Austrian economics Ludwig von Mises [62] quickly realized that without free market prices to tell entrepreneurs what goods and services were in high or low demand, and how scarce or abundant they were, economic calculation would be impossible under socialism and the economy would soon collapse.

18. Ludwig von Mises, Nation, State, and Economy (1919) and Liberalism (1927) vs. Carl Schmitt on Dictatorship (1921), Political Theology (1922), and The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy (1923)

Classical liberals like the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises warned that the interventionist economic policies introduced during the war (“war socialism”), chronic debt, and disruption to free trade would lead to economic collapse, high inflation, and calls from disgruntled consumers and nationalists for radical solutions like socialism and authoritarian governments. Liberal democracy, constitutionalism, and free markets would be abandoned with catastrophic consequences. Mises expressed these concerns very soon after the war ended ion Nation, Staat und Wirtschaft (Nation, State, and Economy) (1919) and accurately predicted many of the events which would occur in the 1920s. [63] He followed this a few years later with a defence of classical liberalism in 1927 with Liberaslismus (Liberalism). [64] At the same time, the conservative German jurist Carl Schmitt laid out his criticisms of parliamentary democracy and his support for strong authoritarian, even dictatorial government in a series of essays on Dictatorship (1921), Political Theology (1922), and The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy (1923). [65] His ideas would have a significant impact on the National Socialist Party after it came to power in 1932.

Another defender of liberal democracy who wrote at the same time was the English historian, jurist, and diplomat Viscount James Bryce (1838-1922) who wrote a detailed defence of democratic government in 1921, the war before he died. [66]

Of course, in the background of these debates, is the much more troubling expression of anti-liberal and democratic thought in the work of Adolph Hitler, Mein Kampf (My Struggle) (1925-26).

19. The Beveridge Report (Social Insurance and Allied Services) (1942) vs. Friedrich Hayek, The Road to Serfdom (1944)

The dramatic increase in government intervention in and control of the economy in wartime became the model for many socialists in peacetime. This was true with German “Kriegsozialismus” (war socialism) in the First World War for the Bolsheviks and for the architects of the British welfare state created after the Second World war by the Labour Party. The Beveridge Report [67] was drawn up during the war with detailed plans on how the first steps in creating a welfare state might be taken using the experience and even the same personnel who worked on government planning during the war. Also during the war, the Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek, [68] who was teaching at the London School of Economics, warned that all the incremental regulations and controls introduced during the war would eventually lead to fully fledged socialism, or what he called a new kind of “serfdom” in his class work The Road to Serfdom (1944).

Conclusion

There are many possible pairings of classic texts with "conflicting" points of view. They could be about disagreements concerning art, music, architecture, literature, and poetry; or they could be about particular debates within science such as the shape of the orbits of the planets, or the nature of evolution; or they could be about the nature of the human mind, or of course, one of the most contentious debates within WC, the nature of God. Each would make a very interesting set of readings to stimulate students and get them debating the issues.

My choice of texts concerns the debate within the WT about the the proper role of political coercion and the function of the state, the extent to which market relations should be free to operate without regulation by the state, and if we are to have a state, how limited should its powers be.

Endnotes

[1] Ludwig von Mises, “The Idea of Liberty is Western” (1950) in Money, Method, and the Market Process. Essays by Ludwig von Mises. Selected by Margin von Mises. Edited and with an Introduction by Richard M. Ebeling (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2016), pp. 309-10.

[2] Quoted in Gertrude Himmelfarb, Lord Acton: A Study in Conscience and Politics (University of Chicago Press: Phoenix Books, 1962), p. 132.

[3] On Goodrich’s association with the Great Books Program see “Chapter 22: Associations and Causes” in Dane Starbuck, The Goodriches: An American Family (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2001). Online elsewhere.

[4] See the Introduction to “The Great Books of Liberty,” The Online Library of Liberty Online elsewhere, the accompanying illustrations, and the list of books which Goodrich believed were the “Great Books about Liberty.”

[5] The “Liberty Matters” online discussion forum began in January, 2013 and to date there have been 40 discussions Online elsewhere. We have had discussions of more traditional authors such as John Locke, David Hume, and Alexis de Tocqueville, but also lesser known figures such as John Trenchard, Germaine de Staël, and Frédéric Bastiat. Of course, we had to have one on Karl Marx last year in the year of the bicentennial of his birth.

[6] See the collection of 13 historical “Debates” at the OLL Online elsewhere and “Some Provocative Pairings of Texts about Liberty and Power” Online elsewhere.

[7] Thomas Hobbes, Hobbes’s Leviathan reprinted from the edition of 1651 with an Essay by the Late W.G. Pogson Smith (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1909). Online.

[8] James Harrington, The Oceana and Other Works of James Harrington, with an Account of His Life by John Toland (London: Becket and Cadell, 1771). Online.

[9] See for example “The First Agreement of the People (3 Nov. 1647)” in An Anthology of Leveller "Agreements" (1647-1649). Edited by David M. Hart (Pittwater Free Press, 2024) Online.

[10] Richard Overton, An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyranny (12 October 1646) in Richard Overton, *An Anthology of the Works of Richard Overton (1641-1649). Edited by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2024). Online

[11] Richard Cumberland, A Treatise of the Laws of Nature, translated, with Introduction and Appendix, by John Maxwell (1727), edited and with a Foreword by Jon Parkin (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2005). Online elsewhere.

[12] The definitive edition is the Glasgow Edition of the Works of Adam Smith. I have online the 1776 edition as well as the Cannan edition: Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, edited with an Introduction, Notes, Marginal Summary and an Enlarged Index by Edwin Cannan (London: Methuen, 1904). 2 vols. Online.

[13] Thomas Mun, “England’s Treasure by Forraign Trade. Or, The Ballance of our Forraign Trade is the Rule of our Treasure,” in John Ramsay McCulloch, A Select Collection of Early English Tracts on Commerce from the Originals of Mun, Roberts, North, and Others, with a Preface and Index (London: Printed for the Political Economy Club, 1856). Online elsewhere.

[14] Friedrich List, Das nationale System der Politischen Oekonomie von Friedrich. Neudruck nach dem Ausgabe letzter Hand, eingerichtet von Professor Dr. Heinrich Waentig. Zweite Auflage. Zweite Auflage (Jena: Verlag von Gustav Fischer, 1910). In Sammlung sozialwissenschaftler Meister III. Herausgegeben von H. Waentig. Online ; Friedrich List, The National System of Political Economy by Friedrich List, trans. Sampson S. Lloyd, with an Introduction by J. Shield Nicholson (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1909). Online].

[15] Frédéric Bastiat, The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat. Vol. 3: Economic Sophisms and “What is Seen and What is Not Seen.” Jacques de Guenin, General Editor. Translation Editor Dennis O’Keeffe. Academic Editor David M. Hart. (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2017). Online elsewhere. See also the French editions: Sophismes économiques. Par M. Frédéric Bastiat, Membre du Conseil général des Landes (Paris: Guillaumin, 1846) and Sophismes économiques. Par M. Frédéric Bastiat. Membre correspondant de l’Institut et du Conseil général des Landes. Deuxième Série. (Paris: Guillaumin, 1848) Online.

[16] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto. A Modern Edition. With an Introduction by Eric Hobsbawm (London: Verso, 1998). Online in English: Manifesto of the Communist Party. By Karl Marx and Frederick Engels. Authorized English translation: Edited and Annotated by Frederick Engels (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1888, 1910) Online]; and German: Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei. Veröffentlicht im Februar 1848. (London: Gedruckt in der Office der “Bildungs-Gesellschaft für Arbeiter” von I. E. Burghard. 1848). Online.

[17] To mark this event we organized a Liberty Matters discussion of Marx in October 2018 on “Marx and the Morality of Capitalism.” Online elsewhere.

[18] Frédéric Bastiat, The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat. Vol. 2: The Law, The State, and Other Political Writings, 1843-1850 (2012), p. 97. Online elsewhere. And the French version: Frédéric Bastiat, L’État. Maudit Argent. Par M. Frédéric Bastiat, Représentant du Peuple. Membre Correspondant de L'institut, et du Conseil Général des Landes (Paris: Guillaumin et Cie, 1849). Online. Bastiat also wrote 12 significant anti-socialist pamphlets between 1848 and 1850, including “Property and Law” (May 1848), “The State” (Sept. 1848), “Protectionism and Communism’ (Jan. 1849), “Plunder and the Law” (May 1850), “The Law” (July 1850), and “What is Seen and What is Not Seen” (July 1850).

[19] I do not have either of these texts available online at the moment.

[20] Thomas Hobbes, Hobbes’s Leviathan reprinted from the edition of 1651 with an Essay by the Late W.G. Pogson Smith (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1909). Online.

[21] Richard Cumberland, A Treatise of the Laws of Nature, translated, with Introduction and Appendix, by John Maxwell (1727), edited and with a Foreword by Jon Parkin (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2005). Online elsewhere.

[22] James Harrington, The Oceana and Other Works of James Harrington, with an Account of His Life by John Toland (London: Becket and Cadell, 1771). Online.

[23] Richard Overton, An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyranny (12 October 1646) in Richard Overton, *An Anthology of the Works of Richard Overton (1641-1649). Edited by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2024). Online.

[24] See for example “The First Agreement of the People (3 Nov. 1647)” in An Anthology of Leveller "Agreements" (1647-1649). Edited by David M. Hart (Pittwater Free Press, 2024) Online.

[25] Robert Filmer, Patriarcha; of the Natural Power of Kings. By the Learned Sir Robert Filmer Baronet (London: Richard Chiswell, 1680). Online.

[26] John Locke, TWO TREATISES OF Government: In the former, The false Principles, and Foundation OF Sir ROBERT FILMER, And his FOLLOWERS, ARE Detected and Overthrown. The latter is an ESSAY CONCERNING THE True Original, Extent, and End OF Civil Government. LONDON, Printed for Awnsham Churchill, at the Black Swan in Ave-Mary-Lane, by Amen-Corner, 1690. Online.

[27] James Tyrrell, Patriarcha non Monarcha. THE Patriarch Unmonarch’d: BEING OBSERVATIONS ON A late Treatise and divers other Miscellanies, Published under the Name of Sir Robert Filmer Baronet. (London: Richard Janeway, 1681). Online.

[28] Montesquieu, Spirit of Laws (1748) Online elsewhere; or in French: Charles Louis de Secondat baron Montesquieu, De l' Esprit ses Lois. Nouvelle Édition, Revue, corrigée, & considérablement augmentéé par l' Auteur. (Londres, MDCCLXXVII (1777). 4 vols. Online.

[29] Destutt de Tracy, A Commentary and Review of Montesquieu’s ’Spirit of Laws’ (1806) Online elsewhere.

[30] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract and Discourses by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, translated with an Introduction by G.D. H. Cole (London and Toronto: J.M. Dent and Sons, 1923). Online. And in French: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Du Contrat Social. Principes du droit politique. Par J. J. Rousseau, Citoyen de Genève. (Amsterdam, chez Marc Michel Rey. MDCCLXII (1762)). Online.

[31] Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments; Or, An Essay towards an Analysis of the Principles by which Men naturally judge concerning the Conduct and Character, first of their Neighbours, and afterwards of themselves. To which is added, a Dissertation on the Origin of Languages. (Printed for A. Strahan at Edinburgh. MDCCXC.) Online.

[32] Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria, An Essay on Crimes and Punishments. By the Marquis Beccaria of Milan. With a Commentary by M. de Voltaire. A New Edition Corrected. (Albany: W.C. Little & Co., 1872) Online elsewhere.

[33] Bentham, “Panopticon; Or, the Inspection-House” (1787) Online elsewhere.

[34] The definitive edition is the Glasgow Edition of the Works of Adam Smith. I have online the 1776 edition as well as the Cannan edition: Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, edited with an Introduction, Notes, Marginal Summary and an Enlarged Index by Edwin Cannan (London: Methuen, 1904). 2 vols. Online.

[35] Thomas Mun, “England’s Treasure by Forraign Trade. Or, The Ballance of our Forraign Trade is the Rule of our Treasure,” in John Ramsay McCulloch, A Select Collection of Early English Tracts on Commerce from the Originals of Mun, Roberts, North, and Others, with a Preface and Index (London: Printed for the Political Economy Club, 1856). Online elsewhere.

[36] Richard Price, “A Discourse on the Love of Our Country” (November 1789) Online elsewhere.

[37] Edmund Burke, Reflections on the French Revolution (1790) in Edmund Burke, Select Works, edited with Introduction and Notes by E.J. Payne. 3 Volumes (Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1874-). Vol. 2. Online..

[38] Thomas Paine, Rights of Man: Being an Answer to Mr. Burke’s attack on the French Revolution. Second edition. By Thomas Paine, Secretary for Foreign Affairs to Congress in the American war, and Author of the work intitled "Common Sense." (London: Printed for J. S. Jordan, no. 166, Fleet-Street. MDCCXCI). Online.

[39] William Godwin, An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, and its Influence on General Virtue and Happiness (London: G.G.J. and J. Robinson, 1793). 2 vols. Online.

[40] Catharine Macaulay, Observations on the Reflections of the Right Hon. Edmund Burke, on the Revolution in France, in a Letter to the Right Hon. the Earl of Stanhope (London: C. Dilly, 1790). Online elsewhere.

[41] Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Men, in a Letter to the Right Honourable Edmund Burke, occaisioned by his Reflections on the Revolution in France (2nd edition) (London, Printed for J. Johnson, 1790). Online; and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects (London: J. Johnson, 1792) Online.

[42] The first edition of 1798 which started the debate, Thomas Robert Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population, as it affects the future improvement of society. with remarks on the speculations of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorcet, and other Writers. London: Printed for J. Johnson, in St. Paul's Church-Yard. 1798. Online; and the much expanded 6th edition of 1826 Thomas Robert Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population, or a View of its Past and Present Effects on Human Happiness; with an Inquiry into our Prospects respecting the Future Removal or Mitigation of the Evils which it Occasions (London: John Murray 1826). 2 vols. 6th ed. Online.

[43] William Godwin, Of Population. An Enquiry concerning the Power of Increase in the Numbers of Mankind (Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1820). Online.

[44] Friedrich List, Das nationale System der Politischen Oekonomie von Friedrich. Neudruck nach dem Ausgabe letzter Hand, eingerichtet von Professor Dr. Heinrich Waentig. Zweite Auflage. Zweite Auflage (Jena: Verlag von Gustav Fischer, 1910). In Sammlung sozialwissenschaftler Meister III. Herausgegeben von H. Waentig. Online ; Friedrich List, The National System of Political Economy by Friedrich List, trans. Sampson S. Lloyd, with an Introduction by J. Shield Nicholson (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1909). Online.

[45] Frédéric Bastiat, The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat. Vol. 3: Economic Sophisms and “What is Seen and What is Not Seen.” Jacques de Guenin, General Editor. Translation Editor Dennis O’Keeffe. Academic Editor David M. Hart. (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2017). Online elsewhere. See also the French editions: Sophismes économiques. Par M. Frédéric Bastiat, Membre du Conseil général des Landes (Paris: Guillaumin, 1846) and Sophismes économiques. Par M. Frédéric Bastiat. Membre correspondant de l’Institut et du Conseil général des Landes. Deuxième Série. (Paris: Guillaumin, 1848) Online.

[46] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto. A Modern Edition. With an Introduction by Eric Hobsbawm (London: Verso, 1998). Online in English: Manifesto of the Communist Party. By Karl Marx and Frederick Engels. Authorized English translation: Edited and Annotated by Frederick Engels (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1888, 1910) Online]; and German: Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei. Veröffentlicht im Februar 1848. (London: Gedruckt in der Office der “Bildungs-Gesellschaft für Arbeiter” von I. E. Burghard. 1848). Online.

[47] Frédéric Bastiat, The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat. Vol. 2: The Law, The State, and Other Political Writings, 1843-1850 (2012), p. 97. Online elsewhere. And the French version: Frédéric Bastiat, L’État. Maudit Argent. Par M. Frédéric Bastiat, Représentant du Peuple. Membre Correspondant de L'institut, et du Conseil Général des Landes (Paris: Guillaumin et Cie, 1849). Online. Bastiat also wrote 12 significant anti-socialist pamphlets between 1848 and 1850, including “Property and Law” (May 1848), “The State” (Sept. 1848), “Protectionism and Communism’ (Jan. 1849), “Plunder and the Law” (May 1850), “The Law” (July 1850), and “What is Seen and What is Not Seen” (July 1850)..

[48] John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1859): John Stuart Mill, On Liberty. By John Stuart Mill. Fourth Edition. (London: Longmans, Green, Reader and Dyer. 1869). Online.

[49] James Fitzjames Stephen, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity (1874) Online elsewhere.

[50] John Stuart Mill, Principles of Political Economy with some of their Applications to Social Philosophy. By John Stuart Mill. In Two Volumes. Seventh Edition. (London: Longmans, Green, Reader And Dyer, 1871). Online.

[51] Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume I: The Process of Capitalist Production, by Karl Marx. Trans. from the 3rd German edition, by Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling, ed. Frederick Engels. Revised and amplified according to the 4th German ed. by Ernest Untermann (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr and Co., 1909). Online. And in german: Karl Marx, Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Oekonomie.Erster Band. Buch I: Der Produktionsprocess des Kapitals. (Hamburg: Otto Meissner, 1867). Online.

[52] See the Liberty Matters discussion of “Frédéric Bastiat and Political Economy (July, 2013)” [Online elsewhere]; the older translation of Economic Harmonies by the Foundation for Economic Education (1964), Frédéric Bastiat, Economic Harmonies, trans by W. Hayden Boyers, ed. George B. de Huszar, introduction by Dean Russell (Irvington-on-Hudson: Foundation for Economic Education, 1996). Online elsewhere; and in French: Frédéric Bastiat, Harmonies économiques. 2me Édition. Augmentée des manuscrits laissés par l’auteur. Publiée par la Société des amis de Bastiat. (Paris: Guillaumin, 1851). Online.

[53] Herbert Spencer, Social Statics: or, The Conditions essential to Happiness specified, and the First of them Developed (London: John Chapman, 1851). Online.

[55] Herbert Spencer, The Principles of Ethics. In Two Volumes (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1896-97). Online.

[56] John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism. Reprinted from Fraser's Magazine (London: Parker, Son, and Bourn, West Strand. 1863). Online.

[57] George Bernard Shaw, Fabian Essays in Socialism, ed. G. Bernard Shaw, American Edition Ed. by H.G. Wilshire (New York: The Humboldt Publishing Co., 1891). 1st ed. 1889. Online.

[58] Thomas Mackay, A Plea for Liberty: An Argument Against Socialism and Socialistic Legislation. Consisting of an Introduction by Herbert Spencer and Essays by Various Writers. Edited by Thomas MacKay (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1891). Online.

[59] Unfortunately, we do not have copy of Edward Bellamy, Looking Backward: 2000-1887 (1888) online.

[60] Eugen Richter, Sozialdemokratische Zukunftsbilder. Frei nach Bebel. Verlag „Fortschritt-Aktiengesellschaft“ (Berlin, November 1893). Online. And in English: Eugen Richter, Pictures of the Socialistic Future (Freely adapted from Bebel), trans. Henry Wright, Introduction by Thomas Mackay (London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1907). Online.

[61] Lenin, The State and Revolution (Aug.-Sept. 1917). Online elsewhere.

[62] Ludwig von Mises presented his ideas first in an article “Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth“ (1920) and then in expanded form in his book Die Gemeinwirtschaft (Socialism) (1922). See the original essay: Ludwig von Mises, "Die Wirtschaftsrechnung im sozialistischen Gemeinwesen" in Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik, 1920-21, 47: 86-121. Online; and the English translation by S. Adler and published in a collection of essays, In Collective Economic Planning, Friedrich A. Hayek, ed. (1935), "Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth". Reprinted Clifton, NJ: Kelley Publishing, 1975, pp. 87–130. Online. And the larger book version (1st ed. 1922): Ludwig Mises, Die Gemeinwirtschaft: Untersuchungen über den Sozialismus. Zweite, umgearbeitete Auflage (Jena: Verlag von Gustav Fischer, 1932). Online. The English translation: Ludwig von Mises, Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis, trans. J. Kahane, Foreword by F.A. Hayek (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1981). Online elsewhere.

[63] Ludwig Mises, Nation, Staat und Wirtschaft. Beiträge zur Politik und Geschichte der Zeit (Wien und Leipzig: Manzsche Verlags- und Universitäts-Buchhandlung, 1919). Online; and the English translation: Ludwig von Mises, Nation, State, and Economy: Contributions to the Politics and History of Our Time, trans. Leland B. Yeager, ed. Bettina Bien Greaves (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2006). Online elsewhere.

[64] Ludwig von Mises, Liberalismus (Jena: Verlag von Gustav Fischer, 1927) Online; English translation: Ludwig von Mises, Liberalism: The Classical Tradition, trans. Ralph Raico, ed. Bettina Bien Greaves (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2005). Online elsewhere.

[65] Carl Schmitt, Dictatorship. From the Origin of the Modern Concept of Sovereignty to Proletarian Class Struggle (1921), trans. by M. Hoelzl and G. Ward, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2014); Political Theology. Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty (1922), trans. by G. Schwab, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005); The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy (1923), trans. by E. Kennedy, (Cambridge/MA: MIT Press, 1985).

[66] Viscount James Bryce, Modern Democracies, (New York: Macmillan, 1921). 2 vols. Online elsewhere.

[67] The Beveridge Report is Online elsewhere.

[68] The Collected Works of F. A. Hayek Volume I. The Road To Serfdom. Text and Documents. The Definitive Edition. Edited by Bruce Caldwell (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2007).